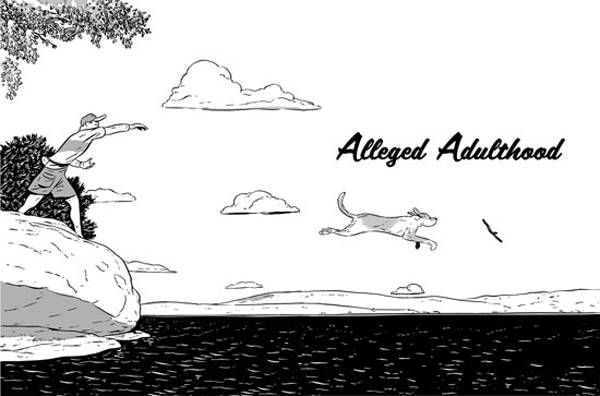

Dog and I (7 page)

Authors: Roy MacGregor

First it was shoes, but now, even if you pop up at dawn, she is at the door with a stick or tennis ball being lolled about the mouth as though it were some precious jewel no one could resist reaching for. She is ready to fetch at midnight, readyâas I discovered several hours backâ to fetch at 3:42

A.M

.

I have tried various solutions. Someone in the house went to one of those new pet megastoresâyou know, the ones that make the West Edmonton Mall look like a corner storeâand returned with a plastic “arm” that you load and that fires the ball with greater ease than a real arm. And at one point I even got out my old lacrosse stick and began tossing the ball so far into the bush that it seemed not even embedded GPS and satellite tracking would find it, all to no avail. In a moment Willow was back, black tongue dragging on the ground, sides frantically panting, ball in mouth so black and goopered there was no longer a hint of green to be seen.

I turned to the internet. On one site, a veterinarian talking about obsessive-compulsive behaviour offers the line, “Women think men have a one-track mind ⦠that is, until they meet a border collie.” Another professional, a dog psychologist it seems, operating out of New York City, suggests Prozac as a possible cure. For the puppy or the owner? The site isn't clear. Either way, a frightening thought.

But not quite so alarming, perhaps, as the soggy black ball that has once again been plunked in my lap. And even if there were such a pill around here, and it was meant for the pet not the human, there is still one problem. How, I wonder, would you ever get it past a mouth that is plugged twenty-four hours a day with a tennis ball?

The Teen Years

Seven for every one. The rule of thumbârule of dewclaw, if you preferâfor measuring dog years against human years is to count seven human years for every one dog year. There is a point, admittedly, where this works fairly well. A nine-year-old mutt, for example, is much the same as a sixty-three-year-old human mongrel. A fifteen-year-old pooch is very much a centenarian with teeth and bladder problems. It falls apart, however, when trying to figure out puppies.

The current subjectâthe one sleeping in the corner over there with all four paws in the airâwill be closing in on a year some time before Christmas. The date is inexact, as might be expected of a mutt of uncertain lineage that a mischievous daughter found in a distant Humane Society. But if we guess ten or eleven months, then this creature named Willow, by the accepted measure, should be roughly kindergarten level.

I don't think so. For one thing, she is too stupid. For another thing, she is too smart.

The seven-for-one math simply does not work in the first year of a dog's life. What human, for example, can walk at two weeks? What human can chew, and partly digest, a shoe at four weeks? What human has ever been known to run away at eight weeks? Find me the human baby who can swim across a bay at six months, let alone a beginning toddler who can chase a car halfway to work at ten months. Show me the child, please, who is house-trained at seven monthsâwell, partly housetrained, anyway.

Then again, we do notâat least I hope notâsee a six-month-old baby insisting on hanging about the house with a dirty sock in her mouth. We do not find an infant demanding cat food instead of the food intended for her. We do not see toddlers taking apart, stitch by stitch, every toy they are ever shown to chomp down and burst the plastic squeaker inside.

It is a difficult measure, admittedly, but I think there is a simple solution: triple the rule of thumb for the first year and, if the dog reaches fifteen, forget even trying and just start treating every extra year as an extra year. By this methodology, it is safe to conclude that the brown and white creature sighing in the corner is a ⦠teenager. Certainly, the signs are irrefutable:

â¢Â  Gets up, eats, goes back to sleep, gets up, goes out, comes in, eats, sleeps, whines if can't go out in evening, eats, sleeps.

â¢Â  Never picks up after herself. There are mismatched socks everywhere, including one in her mouth. There are chewed balls, destroyed squeaky toys, pull toys, animal toys strewn everywhere. If you place them neatly back in her toy box, she spends fifteen minutes hauling them out and placing them, randomly, where they are most likely to be in the way.

â¢Â  Totally, one hundred percent self-absorbed. It is all “me ⦠me â¦

ME!

” all the time. She wants fed, wants out, wants in, wants petted, wants someone to play with her, wants on the bed, wants on the furniture, wants in the refrigerator, wants the cats' food, wants the humans' food, wants to roll in whatever she can findâdead squirrel, crushed groundhog, rotted bird carcass.â¦

â¢Â  Single-minded. If you have seen a teenage human hypnotized, transfixed, and obsessed with a video game, you will have some senseâsome very small senseâof what it's like to see a dog willing to chase a ball or stick much longer than the human arm can throw.

â¢Â  Megalomania. What does it tell you when a dog stops and looks around the field if she happens to catch a thrown ball on the first bounce? What does it tell you when a dog insists on walking through the woods with a log big enough to take down a hiker at the back of the knees? Or when the dog insists on bounding past you just as the trail becomes wide enough for one? What does it say to you when a skinny little puppy suddenly tries to puff up like an Arctic sled dog the moment any other dog comes along the trail?

â¢Â  Whining. Whine to get out, whine to get in. Whine to be fed, whine for more. Whine for a treat, whine for a second treat. Whine to get out, whine to get in. Whine to play, whine to play, whine to play, whine to play.â¦

â¢Â  Stubborn. Approximately once a week does as she is told. Other 4,587 times it's a toss-up. Shall I “come” or shall I scoot? Shall I “sit” or shall I lunge? As for “stay”âdon't even think about it.

â¢Â  Driving. Insists on sitting in best seat. Would prefer driver's seat if available. Wants windows down so she can hang head out.

â¢Â  Clumsy. Fine to hang your head out the car window, but not so fine, she will surely eventually realize, to place paw on automatic window and set reverse guillotine in motion.â¦

Pawprinted Legacies of the Great

I have started reading to my dog. Not stuff I have writtenâ there is, after all, a Humane Society in this townâbut self-improvement books.

Her

self-improvement.

And why not read? Everyone talks to the dog. I even saw a poll somewhere that claimed one out of every three of us telephones the dogâhomesick travellers calling back to have whoever answers hold out the receiver while the deranged traveller tries to coax a bark out of the poor dumbfounded thing. Reading, however, has a far more honourable purpose than the self-gratification of a business traveller feeling sorry for himself. I want this dogâthis one-year-old mutt called Willow, who is just beginning to come into her ownâto become something special, not just something I call home to talk to when nobody else will listen.

The dog needs inspiration. It lay, asleep, legs in the air, the other morning while one of the many unemployed in this house watched

The Ellen DeGeneres Show

. A man was on talking about how, out walking one evening with his Labradors, he had fallen into a diabetic coma. The yellow Lab lay on him to keep the man warm while the black LabâI'm not making this up; I'm not allowed toâgrabbed the flashlight the man had dropped and began running about the field with it in its mouth until a policeman noticed the dancing light and came to investigate.

Thanks to the dogs, the policeman's CPR, and an ambulance, the man's life was saved. When he came back from hospital, he told Ellen, the dogs began to weep.

This dog sleeping on the floor, on the other hand, would pick up a flashlight only if someone first threw it. And then she'd want it thrown again and again and again and again until, frankly, the thrower might welcome a diabetic coma.

Perhaps it's the breed. A couple of months ago, while travelling in the United States, I came across an advice column for pet owners. A woman had written in to say her new dog's constant staring had “weirded” her out to the point where she'd decided to take the little border collie back to the kennel where she got it. The advice columnist, bless his heart, gloriously ripped into her, saying the breed is

supposed

to stare like that. Such dogs, the expert said, are extremely bright. It wasn't staring but rather looking for a signal to do somethingâlike fetch, or round up the sheepâand the only thing dumb about border collies is that they think humans have enough intelligence to offer direction.

This dog isn't quite a border collie, but she is enough of one to stare endlessly in search of a stick or ball that might fly through the air and have to be instantly returned for the next throw. And the next. And the next â¦

So, being a fairly bright human compared with the woman who took her dog back, I have decided to take that columnist's sage advice and offer direction. Which is why I have started reading to my dog. The book we have chosen is

The Pawprints of History

by Stanley Coren, a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia. Subtitled

Dogs and the Course of Human Events,

the book was a gift from a friendâand we are most grateful for its inspiration.

I have explained to Willow that I expect great things from her, but I am not expecting the impossible. It would be unlikely, for example, that she might ever start her own church, though Stanley Coren makes an excellent case that the very existence of Protestantism is directly tied to the intervention of a greyhound called Urian.

According to the Coren interpretation of religious history, Protestantism would never have been necessary to invent had Pope Clement VII only seen fit to grant Henry VIII the divorce he was seeking in order to marry the charming Anne Boleyn. All that was required was for the Pope to grant an annulment on whatever cocked-up and cooked-up basis would suffice. The king dispatched his main churchman, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, off to Rome to ask the favour and Wolsey, a great dog lover, insisted on taking along Urian, his rather overprotective pet.

Custom demanded that supplicants approach the papal throne and kiss the Pope's toe. Wolsey, a good Catholic and a Cardinal, naturally had no difficulty with this, but poor Urian misunderstood the bare foot swinging out toward his master's lips, leapt over his master, and smartly bit Pope Clement VII on the leg. The Pope blew a fuse, threw the Cardinal out, and refused to grant Henry his wishâthereby leading to the creation of the Church of England.

I do not expect a church; I just pray that she one day amounts to

something

.

I have read aloud to Willow the story of Bounce, the dog who saved Alexander Pope from a knife-wielding valet, and of Cap, the sheepdog who inspired Florence Nightingale to take up nursing. I have read to her the remarkable tale of Biche, Frederick the Great's beloved Italian greyhound, who was so valued in battle that, when Biche was captured during the Battle of Soor in 1745, Frederick called it “the kidnapping of a member of the royal family” and arranged a “prisoner exchange” to get the dog back.