Dog Sense (15 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Given that pariah dogs do not organize their societies in the same way that wolves do, it seems unlikely that pet dogs wouldâbut the remote possibility does remain that somehow pet dogs might have re-evolved the desire for dominance that characterizes wolves in zoos and is so beloved of some old-school dog trainers. In order to examine this possibility, my students and I worked at a sanctuary for unhomed dogs in Wiltshire, UK.

2

Such dogs serve as a useful intermediate between the feral and the pet dog, because they all started their lives in domestic circumstances, before being allowed unrestricted access to other similar dogs. At any one time the sanctuary contains about twenty dogs, usually castrated males whose behavior toward people is judged to be too unpredictable for them to be homed. At night they sleep in spacious kennels shared among four or five dogs, but during the day they have the run of a large paddock planted with trees and bushes, littered with toys, and equipped with tunnels through which they can run from one part of the paddock to another.

If any group of pet dogs had the opportunity to establish a wolf-type hierarchy, it would be at a sanctuary like this one in Wiltshire, where the dogs have eight hours a day of unregulated interaction with their own kind. However, many hours of observation failed to reveal anything of the sort. There was plenty of competitive behavior to record: Dogs would growl or bark at one another, pretend to bite each others' necks, attempt

to mount one another, or chase one another around the paddock. Others would react by crouching, looking away, licking their lips, or running off. Yet most of this behavior took place between a minority of the dogs, whom we ended up calling “The Insiders.” Three dogs, “The Hermits,” kept out of the way of all the others, and consequently almost never interacted, so it was difficult to know what their “status,” if any, might have been. Seven others, “The Outsiders,” did not actively avoid The Insiders, but always gave way to them. Relationships between The Insiders themselves were inconsistentâit proved impossible for them to construct any kind of hierarchy, let alone any of the types of hierarchy thought to occur among wolves. Over a third of the interactions took place between just four pairs of dogsâRonnie with Benson (both collie crosses), Jack (a springer) with Eddie (a rough collie), Mickey Brown (a shepherd cross) with Branston (a collie/spaniel), and Dingo (another shepherd cross) with Tarkus (a Weimaraner). Exactly why these pairs of “buddies” had formed was unclearânone, as far as we could tell, were relatedâbut the attachments were certainly not predicted by any aspect of wolf behavior. They do, however, emphasize that dogs, unlike wolves, find it easy to establish harmonious relationships with dogs they are not related to and have not met until both were adult.

Our study of the sanctuary dogs failed to uncover any evidence that dogs have an inclination to form anything like a wolf pack, especially when they are left to their own devices. This reinforces all the other scientific evidence indicating that domestication has stripped dogs of most of the more detailed aspects of wolf sociality, leaving behind only a propensity to prefer the company of kin to non-kinâa propensity shared by many animals and certainly not restricted to wolves or even canids. Nevertheless, many experts on dogs and dog training persist in alluding to the wolf as the essential point of reference for understanding pet dogsâdespite the fact that the wolf they refer to is not the wild wolf, which values family loyalties above all else, but more the captive wolf, which finds itself in a constant battle with the unrelated wolves with which it is forced to live.

Despite all of the evidence indicating that dogs and wolves organize their social lives quite differently, many people still cling to their misguided and outdated comparisons between dogs and wolves. The question

therefore has to be asked again: Does the behavior of the wolf have anything useful to tell us about the behavior of pet dogs?

The misconception that dogs behave like wolves might not matter if it did not seriously misconstrue the dog's motivations for establishing social relationships. The most pervasiveâand perniciousâidea informing modern dog-training techniques is that the dog is driven to set up a dominance hierarchy wherever it finds itself. This idea has led to massive misconceptions about their social relationships, both those between dogs within a household and those between dogs and their owners.

Every dog, conventional wisdom holds, feels an overwhelming need to dominate and control all its social partners. Indeed, the word “dominance” is used widely in descriptions of dog behavior. Dogs that attack people whom they know well are still universally referred to as suffering from “dominance aggression.” The term is sometimes even usedâincorrectlyâto describe a dog's personality. Consider this quote from the American Dog Trainers Network website: “A dominant dog knows what he wants, and sets out to get it, any way he can. He's got charm, lots of it. When that doesn't work, he's got persistence with a capital âP.' And when all else fails him, he's got attitude.”

3

Actually, this is just a description of an unruly, untrained, yet somehow charming dog. It says nothing about what that dog's relationships with other dogs are likeânothing about its relationships, “dominant” or otherwise. Other inaccurate or misleading uses of the term “dominance” abound in dog training. For example, celebrity US trainer Cesar Millan has referred to dogs trying to “dominate” cats, and a dog chasing the light from a laser pointer has been described as trying to “dominate” it,

4

behavior that a biologist would immediately classify as predatory, not social.

Used properly, “dominance” means something quite different from these meanings assigned to it by dog trainers and other experts. The term simply describes a relationship between two individuals at a particular moment in time; it makes no predictions about how that situation arose, about how long it is likely to last, or about the personalities of those individuals. Indeed, a biologist would likely point out that if you put the dominant one of the two in another social situation, it might well end up

not

being “dominant.” Moreover, the term is just a descriptionâit says

nothing about whether the two animals involved are in any way aware that theirs is a “dominance” relationship.

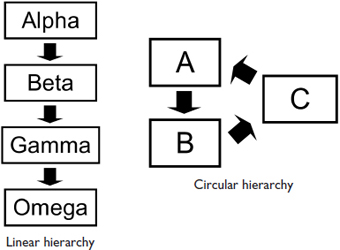

Calling dogs “dominant” suggests that their relationships can be fitted into hierarchies. The concept of “hierarchy” is the corollary of “dominance,” whenever a group consists of more than two individuals. If each pair can be observed to have a dominance relationship, and if those relationships can be arranged in a linear fashion such that each individual is subordinate to all those above it, then a hierarchy can be determined. Sometimes no such hierarchy can be constructed; this is the case, for example, when individuals that should be “low down” in the hierarchy according to most of their relationships nonetheless “dominate” an individual that “dominates” many others and should therefore be “high up” in the hierarchy. Furthermore, just as the pairwise dominance relationships that make up the hierarchy may not be appreciated as such by the individuals involved, so too the hierarchy may not be visible to those within it, even if one is evident to an outside observer.

There is little evidence that hierarchy is a particular fixation of dogs, either in their relationships with other dogs or in those with their owners. Let's first examine what hierarchy is. Let us assume that dominance relationships are based on how much of a single attributeâsay, fighting abilityâa dog possesses: The dog with the most of that “quality” should be dominant over all the other dogs in its household and might be labeled the “alpha”; the dog with the second-largest quantity of fighting ability should be dominant over all the others except the alpha and is conventionally labeled the “beta”; and the dog with the least fighting abilityâthe one that is subordinate to all the other dogsâis labeled the “omega.” In a four-dog household, the hierarchy might look like the linear hierarchy diagrammed on the following page.

Relationships between animals are usually not as simple as this neat hierarchical arrangement. Some may have been resolved by fighting; others, through superior problem-solving ability. Still others may be historical in that the “subordinate” dog was brought into the household as a puppy and has never challenged any of the older adults. When such complexities apply, it may be possible to distinguish consistent relationships between pairs of dogs but impossible to arrange them in a linear hierarchy, as diagrammed on the following page (circular hierarchy).

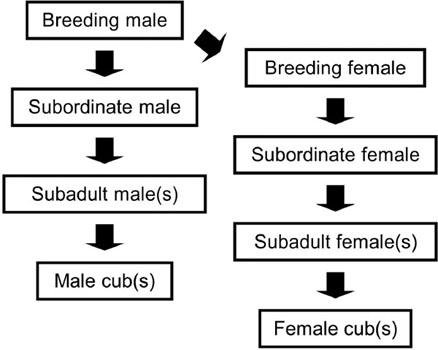

Traditional thinking presumes that the dog's hierarchy stems from the wolf's and, more specifically, that of the captive wolfâbut we now know that this conception is fundamentally misguided. The typical structure of a captive wolf “pack” was thought to be made up of two hierarchies (see

diagram

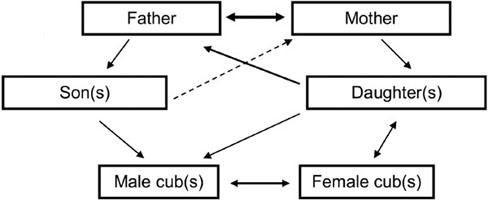

on page 80), one for each sex, although in larger packs these are not entirely linear, since dominance relationships between the juveniles and between the cubs are often indistinct. However, these “hierarchies” are now thought to be an artifact of captivity, whereas the structure of a natural pack depends largely on family allegiances in which no aggression-based hierarchy is at all apparent (see

diagram

on page 80).

In the wild, then, a dominant (or “alpha”) wolf is just the wolf that leads the pack, usually because it is the mother or father of most, or all, of the other members of the pack. The normal way for a wolf to become a “dominant” animal is simply to become sufficiently mature and experienced to be able to find a mate, and then to breed. The term “dominant” thus becomes synonymous with “mother” or “father,” or occasionally “step-mother” or “step-father,” if one of the breeding pair dies and is replaced before the pack breaks up.

Since it is clear that modern wolves are almost certain to be much more wary of man than were the domestic dog's wild ancestors, we should logically consider whether the social grouping preferred by modern wolvesâthe family-based packâis likely to have also been the preferred

social structure of the wolves that became dogs, tens of thousands of years ago. It is, of course, impossible to be sure about how these ancient wolves organized their societies, because social structures don't fossilize. However, we can be confident that wolves lived in packs then as now, because the family unit is the basis for packs wherever it occurs among the canids; family groups are inherently more stable than groups formed by unrelated individuals.

Captive wolf-pack hierarchies

Wolf-pack family structure

Since it was likely shared with ancient wolves, the canids' intrinsically family-based structure is almost certainly the raw material that domestication had to work with. In that case, the most likely explanation for how we have been able to domesticate dogs is that we have been able to insert ourselves into that family structure. By this, I don't mean “family” in the genetic sense; that is clearly impossible. I mean “family” in the sense of a group whose members live together and are able to cooperate because they know one another well. Families do not have to be genetically related to one another in order to function effectively; for instance, as an adopted human baby grows up, it behaves toward its adopting parents as if they were its genetic parents. Although the baby may eventually come to know that it has other, biological parents, this knowledge does not displace the bond that has grown between the baby and the adults who have cared for it. The reason is that, in our species, recognition of immediate family members is largely based upon familiarity, even though we come to overlay this with more conscious knowledge of our actual genetic relationships. Biologically, as a species with a long period of childhood dependency, we are set up to base our family bonds on who looks after us and is affectionate toward us; our instinctive ability to distinguish who is actually related to us genetically is comparatively weak (much weaker than in species with little or no parental care).