Dog Sense (28 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

The human face is particularly expressive. And our facial expressions for the more primitive emotionsâsuch as fear, joy, and angerâappear to be the same the world over. Human expression is clearly a species-typical, evolved trait. The idea underlying this observation was first proposed by Charles Darwin, who attempted to apply the same principle to dogs (see box titled “

Darwin's Dogs

”). Indeed, researchers have recently discovered that the facial muscles used to generate these particular expressions are common to virtually all humans, whereas other facial muscles vary widely between races and between individuals. As a species, we cannot function socially without facial expressionsâfacial paralysis leads almost inevitably to isolation and depression.

Our facial expressions are directly connected to our emotions. Just watch someone's face when she's talking to a friend on the phoneâshe will smile, frown, and so on just as though the other person could see her. Indeed, one of the functions of our facial expressionsâperhaps even their primary functionâis to let people know what we're feeling while we're talking to them. Under those circumstances, we usually express the emotions that we think we

should

be feeling, even if we're not actually experiencing them. The intention in such instances is to convince the speaker not only that we're paying attention to him but that we are also on his emotional wavelength. Overall, our unconscious facial expressions tend to reassure those around us that we are trustworthy.

We also consciously use or suppress many of these same facial expressions to modify the behavior of others to our own benefit. There

is

a direct connection between Emotion III (feelings) and Emotion II (facial expression), but it is under at least some degree of conscious control; indeed, we use our expressions to manipulate those around us. Certain expressions of emotion, such as blushing when we're embarrassed, are almost impossible to fake or suppress, but some people can produce an apparently sincere smile at will. (Others can manage only a fake smile, technically referred to as a non-Duchenne smile, in which the mouth smiles but the eyes don't.) We also try to cover up our emotions when it's socially advantageous to do so: For example, after winning a prize, many people will attempt to block their spontaneous smile by locking their facial muscles or hiding their faces behind their hands, so as to avoid the appearance of gloating. Most of us are adept at detecting false

expressions of emotion in others, even though we may not be able to describe precisely how we have detected an insincerity. Completely masking emotion requires considerable practice, as evidenced by the comparatively few individuals who can achieve a “poker face.” Evolution has evidently given us a highly tuned lie-detection systemâagain, presumably because the success of hunter-gatherer groups depended upon it.

Darwin's Dogs

I

n his book

The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals

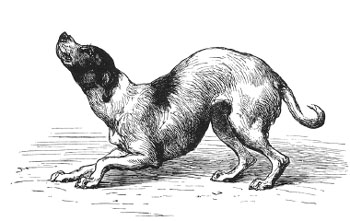

, Darwin used the domestic dog extensively to illustrate his ideas about the interpretation of animals' postures and expressions. One of his central precepts was the “principle of antithesis”âthe idea that opposing emotions induce exactly opposite postures, which thereby convey precise information about the animal's state of mind and intentions. He contrasted the “attacking” dog that stands tall, leans forward with tail and hackles raised, growls, and bares its teeth with the “friendly, submissive” dog that crouches low to the ground, tail held down. Although Darwin's “principle of antithesis” is rarely referred to today, his interpretation of the dogs' emotional states is still considered sound.

Darwin's “attacking” dog

Darwin's “submissive” dog

Are dogs equally manipulative? Dogs do sometimes appear to be “lying” to each other, especially when there is some conflict of interest involvedâalthough as far as I know, no one has studied this systematically. My Labrador retriever Bruno loved people but was always a bit wary of other dogs, especially other males. When he encountered a person he didn't know, he'd wiggle his way up to her, half-crouched, his tail twirling round and round like a demented helicopter. When he saw another male dog, he'd stand as tall as he could, and up would go the hackles on his back. In both instances, Bruno was trying to ensure that the meeting would go the way he wanted it to. In the case of the person, he always wanted to make friends, so he used the wolf-cub greeting. He was trying to make himself look smaller than he really was (an effort that rarely succeeded, considering that he was a rather portly Labrador). Toward another male dog, he did the opposite: He tried to make himself look bigger than he really was. Actually, he was bluffing: If the other dog persisted, he'd quickly change tackâhe wasn't very braveâand back away with his tail tucked down. In other words, he appeared to be trying to mislead the other dog. I don't mean that he was deliberately and consciously setting out to deceive; it is doubtful that dogs have this degree of intelligence. Nevertheless, when attempting to make an impression on a potential rival, most dogs do try to make themselves look bigger than they really are, hoping to scare the other dog off without risking getting hurt in a tussle. However, for this to work every time, the other dog would have to be stupid enough to be taken in by this rather obvious attempt at browbeating. And that seems unlikely.

So why is it that both dogs don't simply signal that they have no intention of fighting? In fact, dogs appear to have no way of negotiating such a climb-down. The first few individuals that adopted the tactic of hackle-raising probably gained an advantage from doing this, because their rivals would have been taken in by it. Once most individuals have adopted the habit of raising their hackles, they will expect their rivals to do the same. Any dog that doesn't raise its hackles will therefore be perceived as

smaller

than it really is, increasing the probability that it will be attacked. Thus this piece of behavior became fixed in the repertoire; almost all dogs will display it from time to time, even if they have little or no intention of actually fighting. Bear in mind, however, that

although their body-language suggests they are bluffing, we have no evidence that dogs are actually aware of this deceptionâthey are simply doing what evolution and their own experiences have told them will achieve the result they want.

A more complex version of this process probably gave rise to the “bared-teeth” signal that many dogs use as the next stage after hackles are raised. Scientists hypothesize that this strategy originated because actual biting of another dog has to be preceded by pulling the jowls out of the way, to protect them. The “bared-teeth” signal is useful for the other dog as well, because it gives a fraction of a second's warning that the first dog is about to bite. Presumably, the baring of teeth was often sufficient to forestall conflict: By raising its top lips well before it bit, a potential attacker could force an inexperienced opponent to recoil without having to submit to the risk of an actual fight. But was this really a sensible bluff? The receiver can now see his opponent's teeth, well in advance of the actual bite. If they're broken or missing, then he can be confident that the resulting bite may not be particularly painful. Thus both parties gain an advantage from the signal: The attacker shows that he may be about to bite, and the target can check how damaging this threat is likely to be if carried out. And so this signal, too, gets fixed in the repertoire. Such signals are especially stable, as far as evolution is concerned, because they contain a kernel of honesty in addition to an element of bluff. The attacker is

really

ready to bite, and the intended victim can

really

get an idea of what the bite will feel like.

Bared teethâan honest signal of fighting potential

The fact that evolution favors a certain degree of bluffing when two animals are in conflict accounts for why animals' emotional states may sometimes be difficult to gauge. But dogs, as highly social animals, evidently have more open communication than many other species do. If early dogs (and wolves) were really in a continual struggle for dominance, evolution should have favored a great deal more dishonest signaling and complete masking of emotionânot a good starting point for domestication. By contrast, cooperation, in dogs as well as in humans, tends to favor transparency. For their ancestor the wolf, sustaining the family unit is essential to survival, so it benefits everyone to know how everyone else is feeling. This principle applied equally well to our own hunter-gatherer ancestors. Hence both

Homo sapiens

and

Canis lupus

usually show their emotions openly, although wolves (and dogs) use their whole bodies, not just their faces, to communicate their emotional state. This happy coincidence must have been one of the factors that smoothed the path of domestication, enabling each species to learn to read each other's minds.

An even greater degree of emotional transparency may have been selected for during domestication, with humans favoring dogs whose body-language was easy to “read” over those that were more inscrutable (that is, until our penchant for unusual features and “baby-faces” started to drive selection in the opposite direction). By implication, those dog owners who are prepared to take the time to learn the signs will find their pets very easy to read.

Although observing dogs' behavior and physiological states can offer clues about dogs' emotions, the connection between physiology and emotion is sometimes murky. A dog's body-language and, more particularly, its attempts to communicate provide one strand of information as to what it is feeling at any given moment (Emotion II). A second strand comes from its hormones and the activity in its brain (Emotion I): Is the dog

internally

stressed, elated, or in a state of anticipation? These physiological changes are invisible to owners and are also not yet well studied by scientists, at least not in the dog. Moreover, what is known indicates that such changes often do not correspond one-to-one with a particular behavior or a single emotional state. For example, stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol can rise not only when the dog is in a situation it finds uncomfortable

but also when it is approaching a potential mating partner. The hormones are preparing the body for activity, not directly reflecting any one emotion. Likewise, most emotions are not simply associated with individual chemicals in the brain. For example, we know that opioid neurochemicals are connected to emotional states, because of the effects on emotion brought about by the narcotics, such as heroin, that mimic them. However, the latter also reduce the perception of pain (e.g., as when morphine is used as an analgesic), so their effects are not simply emotional in nature. Natural opioidsâendorphinsâare produced in the mammalian brain during social bonding activities such as play and mutual physical contact; the fact that their levels are especially low when the animal is distressed by social separation suggests links to several different emotional states.