Domes of Fire (42 page)

Authors: David Eddings

‘You smell good, though,’ Melidere told him.

‘I didn’t set out to be somebody’s supper. Ouch.’

‘Sorry,’ Alean murmured, carefully disengaging her comb from a snarl in his hair. ‘I have to work the dye in, though, or it won’t look right.’ Alean was applying black dye to the young man’s hair.

‘How long will it take me to wash this yellow stuff off?’ Talen asked.

‘I’m not sure,’ Mirtai shrugged. ‘It might be permanent, but it should grow out in a month or so.’

‘I’ll get you for this, Stragen,’ Talen threatened.

‘Hold still,’ Mirtai said again and continued her daubing.

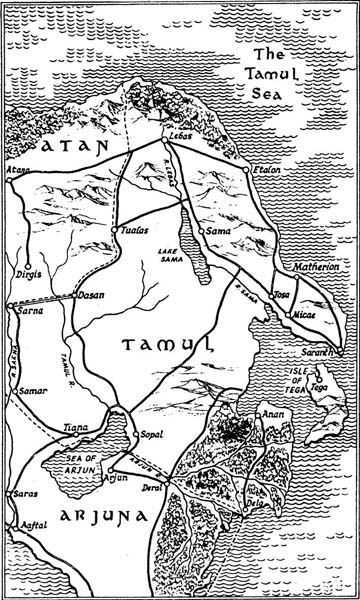

‘We have to make contact with the local thieves,’ Stragen explained. ‘The thieves at Sarsos promised that we’d get a definite answer here in Lebas.’

‘I see a large hole in the plan, Stragen,’ Sparhawk replied. ‘Talen doesn’t speak Tamul.’

‘That’s no real problem,’ Stragen shrugged. ‘The chief of the local thieves is a Cammorian.’

‘How did

that

happen?’

‘We’re very cosmopolitan, Sparhawk. All thieves are brothers, after all, and we recognise the aristocracy of talent. Anyway, as soon as he can pass for a Tamul, Talen’s going to the local thieves’ den to talk with Caalador – that’s the Cammorian’s name. He’ll bring him here, and we’ll be able to talk with him privately.’

‘Why aren’t you the one who’s going?’

‘And get saffron all over my face? Don’t be silly, Sparhawk.’

Caalador the Cammorian was a stocky, red-faced man with curly black hair and an open, friendly countenance. He looked more like a jovial innkeeper than a leader of thieves and cutthroats. His manner was bluff and good humoured, and he spoke in the typical Cammorian drawl and with the slovenly grammar that bespoke back-country origins. ‘So yer the one ez has got all the thieves of Daresia so sore perplexed,’ he said to Stragen when Talen presented him.

‘I’ll have to plead guilty on that score, Caalador,’ Stragen smiled.

‘Don’t never do that, brother. Alluz try’n lie yer way outten thangs.’

‘I’ll try to remember that. What are you doing so far from home, my friend?’

‘I mought ax you the same question, Stragen. It’s a fur piece from here t’ Thalesia.’

‘And quite nearly as far from Cammoria.’

‘Aw, that’s easy explained, m’ friend. I storted out in life ez a poacher, ketchin’ rabbits an’ sich in the bushes on land that weren’t rightly mine, but that’s a sore hard kinda work with lotsa’ risk and mighty slim profit, so I tooken t’ liftin’ chickens outten hen-roosts – chickens

not runnin’ near ez fast ez rabbits, especial at night. Then I moved up t’ sheep-stealing – only one night I had me a set-to with a hull passel o’ sheep-dawgs which it wuz ez betrayed me real cruel by not stayin’ bribed.’

‘How do you bribe a dog?’ Ehlana asked curiously.

‘Easiest thang in the world, little lady. Y’ thrun ‘em some meat-scraps t’ keep ther attention. Well, sir, them there dawgs tore into me somethin’ fierce, an’ I lit out – leavin’, misfortunate-like, a hat which it wuz I wuz partial to an’ which it wuz ez could be rekonnized ez mine by half the parish. Now, I’m jist a country boy at hort ‘thout no real citified ways t’ get me by in town, an’ so I tooken t’ sea, an’ t’ make it short, I fetched up on this yere furrin coast an’ beat my way inland, the capting of the ship I wuz a-sailin’ on wantin’ t’ talk t’ me ‘bout some stuff ez had turnt up missin’ fum the cargo hold, y’ know.’ He paused. ‘Have I sufficiently entertained you as yet, Milord Stragen?’ he grinned.

‘Very, very good, Caalador,’ Stragen murmured. ‘Convincing – although it was a trifle overdone.’

‘A failing, Milord. It’s so much fun that I get carried away. Actually, I’m a swindler. I’ve found that posing as an ignorant yokel disarms people. No one in this world is as easy to gull as the man who thinks he’s smarter than you are.’

‘Ohh.’ Ehlana’s tone was profoundly disappointed.

‘Wuz yer Majesty tooken with the iggernent way I wuz atalkin’?’ Caalador asked sympathetically. ‘I’ll do ‘er agin, iff’n yer of a mind – of course it takes a beastly long time to get to the point that way.’

She laughed delightedly. ‘I think you could charm the birds out of the bushes, Caalador,’ she told him.

‘Thank you, your Majesty,’ he said, bowing with fluid grace. Then he turned back to Stragen. ‘Your proposal has baffled our Tamul friends, Milord,’ he said. ‘The demarcation line between corruption and outright theft

is very clearly defined in the Tamul culture. Tamul thieves are quite class-conscious, and the notion of actually co-operating with the authorities strikes them as unnatural for some reason. Fortunately, we Elenes are far more corrupt than our simple yellow brothers, and Elenes seem to rise to the top in our peculiar society – natural talent, most likely.

We

saw the advantages of your proposal immediately. Kondrak of Darsas was most eloquent in his presentation. You seem to have impressed him enormously. The disturbances here in Tamuli have been disastrous for business, and when we began reciting profit and loss figures to the Tamuls, they started to listen to reason. They agreed to co-operate – grudgingly, I’ll grant you, but they

will

help you to gather information.’

‘Thank God!’ Stragen said with a vast sigh of relief. ‘The delay was beginning to make me very, very nervous.’

‘Y’d made promises t’ yer queen, an’ y’ wuzn’t shore iff’n y’ could deliver, is that it?’

‘That’s very, very close, my friend.’

‘I’ll give you the names of some people in Matherion.’ Caalador looked around. ‘Private-like, if’n y’ take my meanin’,’ he added. ‘It’s all vury well t’ talk ‘bout lendin’ a helpin’ hand an’ sich, but ‘taint hordly nach’ral t’ be namin’ no names right out in fronta no queens an’ knights an’ sich.’ He grinned impudently at Ehlana. ‘An’ now, yer queenship, how’d y’ like it iff’n I wuz t’ spin y’ a long, long tale ‘bout my advenchoors in the shadowy world o’ crime?’

‘I’d be delighted, Caalador,’ she replied eagerly.

Another of the injured knights died that night, but the two dozen sorely-wounded seemed on the mend. As Oscagne had told them, Tamul physicians were extraordinarily skilled, although some of their methods were

strange to Elenes. After a brief conference, Sparhawk and his friends decided to press on to Matherion. Their trek across the continent had yielded a great deal of information, and they all felt that it was time to combine that information with the findings of the Imperial government.

And so they set out from Lebas early one morning and rode south under a kindly summer sky. The countryside was neat, with crops growing in straight lines across weedless fields marked off with low stone walls. Even the trees in the woodlands grew in straight lines, and all traces of unfettered nature seemed to have been erased. The peasants in the fields wore loose-fitting trousers and shirts of white linen and tightly-woven, straw hats that looked not unlike mushroom-tops. Many of the crops grown in this alien countryside were unrecognisable to the Elenes – odd-looking beans and peculiar grains. They passed Lake Sama and saw fishermen casting nets from strange-looking boats with high prows and sterns, boats of which Khalad profoundly disapproved. ‘One good gust of wind from the side would capsize them,’ was his verdict.

They reached Tosa, some sixty leagues to the north of the capital, with that sense of impatience that comes near the end of every long journey.

The weather held fair, and they set out early and rode late each day, counting off every league put behind them. The road followed the coast of the Tamul sea, a low, rolling coast-line where rounded hills rose from broad beaches of white sand and long waves rolled in to break and foam and slither back out into deep blue water.

Eight days – more or less – after they left Tosa, they set up for the night in a park-like grove with an almost holiday air, since Oscagne assured them that they were no more than five leagues from Matherion.

‘We could ride on,’ Kalten suggested. ‘We’d be there by morning.’

‘Not on your life, Sir Kalten,’ Ehlana said adamantly. ‘Start heating water, gentlemen, and put up a tent we can use for bathing. The ladies and I are

not

going to ride into Matherion with half the dirt of Daresia caked on us – and string some lines so that we can hang our gowns out to air and to let the breeze shake the wrinkles out of them.’ She looked around critically. ‘And then, gentlemen, I want you to see to yourselves and your equipment. I’ll inspect you before we set out tomorrow morning, and I’d better not find one single speck of rust.’

Kalten sighed mournfully. ‘Yes, my Queen,’ he replied in a resigned tone of voice.

They set out the following morning in a formal column with the carriage near the front. Their pace was slow to avoid raising dust, and Ehlana, gowned in blue and crowned with gold and diamonds, sat regally in the carriage, looking for all the world as if she owned everything in sight. There had been one small but intense disagreement before they set out, however. Her Highness, the Royal Princess Danae, had objected violently when told that she

would

wear a proper dress and a delicate little tiara. Ehlana did not cajole her daughter about the matter, but instead she did something she had never done before. ‘Princess Danae,’ she said quite formally, ‘I am the queen. You

will

obey me.’

Danae blinked in astonishment. Sparhawk was fairly certain that no one had

ever

spoken to her that way before. ‘Yes, your Majesty,’ she replied finally in a suitably submissive tone.

Word of their approach had preceded them, of course. Engessa had seen to that, and as they rode up a long hill about mid-afternoon, they saw a mounted detachment of ceremonial troops wearing armour of black

lacquered steel inlaid with gold awaiting them at the summit. The honour guard was drawn up in ranks on each side of the road. There were as yet no greetings, and when the column crested the hill, Sparhawk immediately saw why.

‘Dear God!’ Bevier breathed in awed reverence.

A crescent-shaped city embraced a deep blue harbour below. The sun had passed its zenith, and it shone down on the crown of Tamuli. The architecture was graceful, and every building had a dome-like, rounded roof. It was not so large as Chyrellos, but it was not the size which had wrung that reverential gasp from Sir Bevier. The city was dazzling, but its splendour was not the splendour of marble. An opalescent sheen covered the capital; a shifting rainbow-hued fire that blazed beneath the surface of its very stones, a fire that at times blinded the eye with its stunning magnificence.

‘Behold!’ Oscagne intoned quite formally. ‘Behold the seat of beauty and truth! Behold the home of wisdom and power! Behold fire-domed Matherion, the centre of the world!’

‘It’s been that way since the twelfth century,’ Ambassador Oscagne told them as they were escorted down the hill toward the gleaming city.

‘Was it magic?’ Talen asked him. The young thief’s eyes were filled with wonder.

‘You might call it that,’ Oscagne said wryly, ‘but it was the kind of magic one performs with unlimited money and power rather than with incantations. The eleventh and twelfth centuries were a foolish period in our history. It was the time of the Micaen Dynasty, and they were probably the silliest family to ever occupy the throne. The first Micaen emperor was given an ornamental box of mother-of-pearl – or nacre, as some call it – by an emissary from the Isle of Tega when he was about fourteen years old. History tells us that he would sit staring at it by the hour, paralysed by the shifting colours. He was so enamoured of the nacre he had his throne sheathed in the stuff.’

‘That must have been a fair-sized oyster,’ Ulath noted.

Oscagne smiled. ‘No, Sir Ulath. They cut the shells into little tiles and fit them together very tightly. Then they polish the whole surface for a month or so. It’s a very tedious and expensive process. Anyway, the second Micaen emperor took it one step further and sheathed the columns in the throne-room. The third sheathed the walls, and on and on and on. They sheathed the palace, then the whole royal compound. Then they went after the public buildings. After two hundred years, they’d cemented those little tiles all over every building in Matherion. There are low dives down

by the waterfront that are more magnificent than the Basilica of Chyrellos. Fortunately the dynasty died out before they paved the streets with it. They virtually bankrupt the empire and enormously enriched the Isle of Tega in the process. Tegan divers became fabulously wealthy plundering the sea floor.’

‘Isn’t mother-of-pearl almost as brittle as glass?’ Khalad asked him.

‘It is indeed, young sir, and the cement that’s used to stick it to the buildings isn’t all that permanent. A good wind-storm fills the streets with gleaming crumbs and leaves all the buildings looking as if they’ve got the pox. As a matter of pride, the tiles have to be replaced. A moderate hurricane can precipitate a major financial crisis in the empire, but we’re saddled with it now. Official documents have referred to “Fire-domed Matherion” for so long that it’s become a cliche. Like it or not, we have to maintain this absurdity.’

‘It

is

breath-taking, though,’ Ehlana marvelled in a slightly speculative tone of voice.

‘Never mind, dear,’ Sparhawk told her quite firmly.

‘What?’

‘You can’t afford it. Lenda and I almost come to blows every year hammering out the budget as it is.’

‘I wasn’t seriously considering it, Sparhawk,’ she replied. ‘Well – not

too

seriously, anyway,’ she added.

The broad avenues of Matherion were lined with cheering crowds that fell suddenly silent as Ehlana’s carriage passed. The citizens stopped cheering as the Queen of Elenia went by because they were too busy grovelling to cheer. The formal grovel involved kneeling and touching the forehead to the paving-stones.

‘What are they

doing?

’ Ehlana exclaimed.

‘Obeying the emperor’s command, I’d imagine,’ Oscagne replied. ‘That’s the customary sign of respect for the imperial person.’

‘Make them stop!’ she commanded.

‘Countermand an imperial order? Me, your Majesty? Not very likely. Forgive me, Queen Ehlana, but I like my head where it is. I’d rather not have it displayed on a pole at the city gate. It is quite an honour, though. Sarabian’s ordered the population to treat you as his equal. No emperor’s ever done that before.’

‘And the people who don’t fall down on their faces are punished?’ Khalad surmised with a hard edge to his voice.

‘Of course not. They do it out of love. That’s the official explanation, of course. Actually, the custom originated about a thousand years ago. A drunken courtier tripped and fell on his face when the emperor entered the room. The emperor was terribly impressed, and characteristically, he completely misunderstood. He awarded the courtier a dukedom on the spot. People aren’t banging their faces on the cobblestones out of fear, young man. They’re doing it in the hope of being rewarded.’

‘You’re a cynic, Oscagne,’ Emban accused the ambassador.

‘No, Emban, I’m a realist. A good politician always looks for the worst in people.’

‘Someday they may surprise you, your Excellency,’ Talen predicted.

‘They haven’t yet.’

The palace compound was only slightly smaller than the city of Demos in eastern Elenia. The gleaming central palace, of course, was by far the largest structure in the grounds. There were other palaces, however – glowing structures in a wide variety of architectural styles. Sir Bevier drew in his breath sharply. ‘Good Lord!’ he exclaimed. ‘That castle over there is almost an exact replica of the palace of King Dregos in Larium.’

‘Plagiarism appears to be a sin not exclusively committed by poets,’ Stragen murmured.

‘Merely a genuflection toward cosmopolitanism, Milord,’ Oscagne explained. ‘We

are

an empire, after all, and we’ve drawn many different peoples under our roof. Elenes like castles, so we have a castle here to make the Elene Kings of the western empire feel more comfortable when they come to pay a call.’

‘The castle of King Dregos certainly doesn’t gleam in the sun the way that one does,’ Bevier noted.

‘That was sort of the idea, Sir Bevier,’ Oscagne smiled.

They dismounted in the flagstoned, semi-enclosed court before the main palace, where they were met by a horde of obsequious servants.

‘What does he want?’ Kalten asked, holding off a determined-looking Tamul garbed in crimson silk.

‘Your shoes, Sir Kalten,’ Oscagne explained.

‘What’s wrong with my shoes?’

‘They’re made of steel, Sir Knight.’

‘So? I’m wearing armour. Naturally my shoes are made of steel.’

‘You can’t enter the palace with steel shoes on your feet. Leather boots aren’t even permitted – the floors, you understand.’

‘Even the floors are made of sea-shells?’ Kalten asked incredulously.

‘I’m afraid so. We Tamuls don’t wear shoes inside our houses, so the builders went ahead and tiled the floors of the buildings here in the imperial compound as well as the walls and ceilings. They didn’t anticipate visits by armoured knights.’

‘I can’t take off my shoes,’ Kalten objected, flushing.

‘What’s the problem, Kalten?’ Ehlana asked him.

‘I’ve got a hole in one of my socks,’ he muttered, looking dreadfully embarrassed. ‘I can’t meet an

emperor with my toes hanging out.’ He looked around at his companions, his face pugnacious. He held up one gauntleted fist. ‘If anybody laughs, there’s going to be a fight,’ he threatened.

‘Your dignity’s secure, Sir Kalten,’ Oscagne assured him. ‘The servants have down-filled slippers for us to wear inside.’

‘I’ve got awfully big feet, your Excellency,’ Kalten pointed out anxiously. ‘Are you sure they’ll have shoes to fit me?’

‘Don’t be concerned, Kalten-Knight,’ Engessa said. ‘If they can fit

me

, they can certainly fit you.’

Once the visitors had been re-shod, they were escorted into the palace. There were oil lamps hanging on long chains suspended from the ceiling, and the lamplight set everything aflame. The shifting, rainbow-hued colours of the walls, floors and ceiling of the broad corridors dazzled the Elenes, and they followed the servants all bemused.

There were courtiers here, of course – no palace is complete without them – and like the citizens in the streets outside, they grovelled as the Queen of Elenia passed.

‘Don’t become too enamoured of their mode of greeting, love,’ Sparhawk warned his wife. ‘The citizens of Cimmura wouldn’t adopt it no matter what you offered them.’

‘Don’t be absurd, Sparhawk,’ she replied tartly. ‘I wasn’t even considering it. Actually, I wish these people would stop. It’s really just a bit embarrassing.’

‘That’s my girl,’ he smiled.

They were offered wine and chilled, scented water to dab on their faces. The knights accepted the wine enthusiastically, and the ladies dutifully dabbed.

‘You really ought to try some of this, father,’ Princess Danae suggested, pointing at one of the porcelain basins

of water. ‘It might conceal the fragrance of your armour.’

‘She has a point, Sparhawk,’ Ehlana agreed.

‘Armour’s supposed to stink,’ he replied, shrugging. ‘If an enemy’s eyes start to water during a fight, it gives you a certain advantage.’

‘I knew there was a reason,’ the little princess murmured.

Then they were led into a long corridor where mosaic portraits were inlaid into the walls, stiff, probably idealised representations of long-dead emperors. A broad strip of crimson carpet with a golden border along each edge protected the floor of that seemingly endless corridor.

‘Very impressive, your Excellency,’ Stragen murmured to Oscagne after a time. ‘How many more miles is it to the throne-room?’

‘You are droll, Milord.’ Oscagne smiled briefly.

‘It’s artfully done,’ the thief observed, ‘but doesn’t it waste a great deal of space?’

‘Very perceptive, Milord Stragen.’

‘What’s this?’ Tynian asked.

‘The corridor curves to the left,’ Stragen replied. ‘It’s hard to detect because of the way the walls reflect the light, but if you look closely, you can see it. We’ve been walking around in a circle for the past quarter of an hour.’

‘A spiral, actually, Milord Stragen,’ Oscagne corrected him. ‘The design was intended to convey the notion of immensity. Tamuls are of short stature, and immensity impresses us. That’s why we’re so fond of the Atans. We’re reaching the inner coils of the spiral now. The throne-room’s not far ahead.’

The corridors of shifting fire were suddenly filled with a brazen fanfare as hidden trumpeters greeted the queen and her party. That fanfare was followed by an awful screeching punctuated by a tinny clanking noise. Mmrr,

nestled in her little mistress’ arms, laid back her ears and hissed.

‘The cat has excellent musical taste,’ Bevier noted, wincing at a particularly off-key passage in the ‘music’.

‘I’d forgotten that,’ Sephrenia apologised to Vanion. ‘Try to ignore it, dear one.’

‘I

am

,’ he replied with a pained expression on his face.

‘You remember that Ogress I told you about?’ Ulath asked Sparhawk, ‘The one who fell in love with that poor fellow up in Thalesia?’

‘Vaguely.’

‘When she sang to him, it sounded almost exactly like that.’

‘He went into a monastery to get away from her, didn’t he?’

‘Yes.’

‘Wise decision.’

‘It’s an affectation of ours,’ Oscagne explained to them. ‘The Tamul language is very musical when it’s spoken. Pretty music would seem commonplace, even mundane – so our composers strive for the opposite effect.’

‘I’d say they’ve succeeded beyond human imagination,’ Baroness Melidere said. ‘It sounds like someone’s torturing a dozen pigs inside an iron works.’

‘I’ll convey your observation to the composer, Baroness,’ Oscagne told her. ‘I’m sure he’ll be pleased.’

‘

I’d

be pleased if his song came to an end, your Excellency.’

The vast doors that finally terminated the endless-seeming corridor were covered with beaten gold, and they swung ponderously open to reveal an enormous, domed hall. Since the dome was higher than the surrounding structures, the illumination in the room came through inch-thick crystal windows high overhead. The sun poured down through those windows to set the

walls and floor of Emperor Sarabian’s throne room afire. The hall was of suitably stupendous dimensions, and the expanses of nacreous white were broken up by accents of crimson and gold. Heavy red velvet draperies hung at intervals along the glowing walls, flanking columnar buttresses inlaid with gold. A wide avenue of crimson carpet led from the huge doors to the foot of the throne, and the room was filled with courtiers, both Tamul and Elene.

Another fanfare announced the arrival of the visitors, and the Church Knights and the Peloi formed up in military precision around Queen Ehlana and her party. They marched with ceremonial pace down that broad, carpeted avenue to the throne of his Imperial Majesty, Sarabian of Tamul.

The ruler of half the world wore a heavy crown of diamond-encrusted gold, and his crimson cloak, open at the front, was bordered with wide bands of tightly-woven gold thread. His robe was gleaming white, caught at the waist by a wide golden belt. Despite the splendour of his throne-room and his clothing, Sarabian of Tamul was a rather ordinary-looking man. His skin was pale by comparison with the skin of the Atans, largely, Sparhawk surmised, because the emperor was seldom out of doors. He was of medium stature and build and his face was unremarkable. His eyes, however, were far more alert than Sparhawk had expected. When Ehlana entered the throne-room, he rose somewhat hesitantly to his feet.

Oscagne looked a bit surprised. ‘That’s amazing,’ he said. ‘The emperor never stands to greet his guests.’

‘Who are the ladies gathered around him?’ Ehlana asked in a quiet voice.

‘His wives,’ Oscagne replied, ‘the Empresses of Tamuli. There are nine of them.’

‘Monstrous!’ Bevier gasped.

‘Political expediency, Sir Knight,’ the ambassador explained. ‘An ordinary man has only one wife, but the emperor has to have one from each kingdom in the empire. He can’t really show favouritism, after all.’

‘It looks as if one of the empresses forgot to finish dressing,’ Baroness Melidere said critically, staring at one of the imperial wives, a sunny-faced young woman who stood naked to the waist with no hint that her unclad state caused her any concern. The skirt caught around her waist was a brilliant scarlet, and she had a red flower in her hair.

Oscagne chuckled. ‘That’s our Elysoun,’ he smiled. ‘She’s from the Isle of Valesia, and that’s the costume – or lack of it – customary among the islanders. She’s a totally uncomplicated girl, and we all love her dearly. The normal rules governing marital fidelity have never applied to the Valesian Empress. It’s a concept the Valesians can’t comprehend. The notion of sin is alien to them.’