Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (14 page)

Read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Nonfiction, #Biography, #History

Off to school

SCHOOL

Vanessa goes away to school when I am four. Packets come for me from the Correspondence School in Salisbury. Cloud makes me a small chair and table at the woodwork shop and paints them blue and the table sits next to Dad’s desk on the veranda. In the morning, after breakfast, I sit down with Mum and the wad of papers from Salisbury and I write my “Story of the Day” and I learn to color, count, paint. Once a week after lunch, Mum turns on the radio and we listen to

School on the Air

and I throw beanbags around the sitting room and pronounce (“Say after me”) the colors of the rainbow and the names of the shapes, and I walk like a giant and (“Now, then, very softly”) like a fairy and Mum lies on the sofa and reads her book.

But the afternoons are long and hot and buzzing with fat flies and lizards lying still on the windowsills, and Mum is resting, and my nanny—my nanny of the moment; they seem to change like the seasons—has gone off for lunch. So I recruit children (picanins, I call them) from the compound and force them to play “boss and boys” with me. Of course, I am always the boss and they are always the boys.

“Fetch

mahutchi

!”

“Yes, boss.”

“Quicker than that! Run. Boss up! Boss up! Come on,

faga moto

!”

The children run off and fetch an imaginary horse for me.

“Now brush him!” I shout. “No, not like

that.

Like

this.

Hell man, you guys are a bunch of Dozy Arabs.” And I push the children away from the invisible horse to demonstrate the action of a currycomb, a body brush, hoof pick.

My nanny comes back from her lunch and she presses her lips at me. She claps her hands at my “boys” and shoos them away, like chickens. They run down the drive, holding their mouths with insolent laughter, and shout insults back to me in Shona.

“Why did you send my boys away?”

“They are not your boys. They are children like you. Girls and boys.”

I’ve told her that if she shouts at me I will fire her. But now I say, “I was only playing.”

“You were bossing.”

“So?”

She says, “Are you grown-up?”

I frown and push out my worm-pregnant belly.

She says, “When you can reach your hand over your head like this”—and she reaches a hand up, over the top of her head, and covers the opposite ear—“then it means you are grown. Then you can boss other children and you can fire me.”

“I can fire you if I like. Anytime I want, I can fire you.”

“Aiee.”

I reach my hand over the top of my head but it only reaches halfway down the other side.

“See?” she says.

In the later afternoon, after the laundry has been washed and hung up in bright flags at the back of the house, my nanny stands under the tap at the back of the house and rubs green soap on her legs. She doesn’t wash the soap off again, so her legs stay shiny and smooth and the color of light chocolate. If she leaves her legs without soap, I can draw pictures on her dry skin with the sharp end of a small stick and the picture shows up gray on her skin. If I fall, or hurt myself, or if I’m tired, my nanny lets me put my hand down her shirt onto her breast and I can suck my thumb and feel how soft she is, and her breasts are full and soft and smell of the way rain smells when it hits hot earth. I know, without knowing why, that Mum would smack me if she saw me doing this.

My nanny sings to me in Shona.

“Eh, oh-oh eh, nyarara mwana.”

“What song is that?”

“A song for my children.”

“What does it say?”

She tuts, sucking on her teeth. “You are not my children.”

And then, the year I turn eight, I am too old for a nanny anymore. I am ready for boarding school. I get my own trunk with my full, proper name, “Alexandra Fuller,” printed on the top.

“But I thought my name is Bobo.”

“Not anymore. You’re Alexandra now. That’s your real name.”

Dad takes a photograph of us leaving the farm for my first day of big school in January 1977.

Vanessa is almost as tall as Mum. I am holding the Uzi, pressing out my belly to help catch the weight of it. We are standing in front of Lucy, the mine-proofed Land Rover.

Chancellor Junior School is an “A” school, for white children only. This means we have over one hundred acres of grounds: a rugby field, a cricket pitch, hockey fields, tennis courts, a swimming pool, an athletics track, a roller-skating rink. After independence, the skating rink is turned into a basketball court and half the athletics track is turned into a soccer pitch. Basketball and soccer are things white children do not do (like picking your nose in public, mixing cement with tea and bread in your mouth, dancing hip-waggling to African music).

We have our very own extensive library and more than enough books to go around. We have more than enough very well-trained (only white) teachers to go around, including a remedial teacher for the remedial kids, whom we call retards. The retards have their own room at the end of the block (all of them together, regardless of age) and they have to sit in front of everyone else in assembly, even in front of the Standard 1s. And no one plays with them at break or after school and they are excused from athletics practice.

We have music teachers, art teachers, sewing teachers, woodwork teachers, a Red Cross teacher, a tennis coach, a cricket coach, a rugby coach, and an athletics coach, who also teaches us how to swim. Our matrons are white. They’re old, and crazy, but they’re white.

The groundsmen and cleaners are black, supervised by a drunken old white man who keeps whisky and peppermints in the broom cupboard.

The cooks are black, supervised by an old white lady who has spectacularly high hair and who sits in the cool room outside the kitchen drinking tea and reading books with pictures of ladies (whose boobs are about to pop out of their dresses) fainting into men’s arms on the covers.

The maids who do our laundry are black and are supervised by the senior girls’ matron, who is deaf and so tired she spends most of the day half asleep with the radio on in her sitting room. Her room smells of old lady and mothballs.

The boardinghouse we call a hostel, a massive redbrick colonial building that was an army barracks once. It sleeps two hundred children. Forty kids per dormitory, each with a footlocker in which we keep the set of clothes for the week; one set of school uniform and one set of play clothes to last seven days, new brookies and socks daily.

Milk of magnesia, administered by our hook-nosed matron every Friday, keeps us regular. Although the fish, also administered on Friday, usually takes care of any constipation we may have been suffering from.

We wash our hair on Saturday mornings and periodically we are doused with a scalp-stinging mixture that is supposed to kill lice.

The boys are punished with stripes—a leather strap, which hangs in the teachers’ common room. Afterward, we ask to see the pattern of welts on their bums and we ask if they cried and although their faces are streaked and we have heard their shouts of pain they shake their heads, no.

The girls are hardly ever beaten. For our punishments, we are made to kneel on a cement floor for half an hour. Or write out lines: “I will not talk after lights out. I will not talk after lights out,” four hundred times. Or memorize passages from the Bible: “Let us walk honestly, as in the day; not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying. But put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh, to fulfil the lusts thereof.”

The two hundred boarders are mostly children from farms around Umtali, and the two hundred day scholars are townies and we despise and torture them, luring them up into the pine forest, where we attack them and steal their packed lunches. We are better athletes and worse students and tougher fighters than the day-bugs. It is rare that we allow a townie into the rarefied circle of friends and alliances and conspirators that makes up the boarders’ gang. But every morning we meet, in class lines, in the Assembly Hall to sing.

Morning has broken, like the first morning,

Blackbird has spoken, like the first bird.

And a chosen senior kid reads from the Bible, mumbling nervous words. We pray for the army guys. We say the “Ah Father.” And then we go back to our classrooms and stand behind our desks and say another prayer, also for the army guys. Some of the kids, whose dads or brothers have been killed in the War, cry every morning. Their soft sobs are part of the praying.

There are not very many townies with dead dads and brothers. Most of the dead dads and brothers are farmers; killed on patrol, or in an ambush, or by a land mine, or during a farm attack.

On Wednesday before lunch we take Scripture Class from a teacher with hairy legs and sandals (which gives our regular teacher a break to go and smoke cigarettes and drink tea in the teachers’ lounge). On Saturday, another woman (also with hairy legs and sandals, so that I come to associate Christian women with these particular characteristics) comes to the boardinghouse from the Rhodesian Scripture Union and we have to sit in the prep room while the sun and the fields call to us from outside. She tells us Bible stories and makes us pray and hold hands and sing the kinds of songs which require clapping and hopping up and down. On Sunday we walk in snaking lines toward our various churches; Vanessa and I are Anglicans; my best friend is Presbyterian (“Press-button”). There are also Dutch Reformed, Catholics (“Cattle-ticks”), and a fistful of Baptists and Methodists.

But all denominations, all the time, focus prayers and singing and scripture on the War and we all ask God to take care of our army guys and keep them safe from terrorists and we assume that God knows this means (without us actually coming right out and saying it) that we want to win the War.

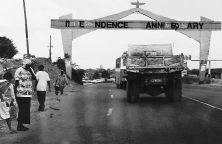

Independence Arch

INDEPENDENCE

Which is why it is such a surprise when we lose the War.

Lost. Like something that falls between the crack in the sofa. Like something that drops out of your pocket. And after all that praying and singing and hours on our knees, too.

Ian Smith rings the Independence Bell thirteen times, one ring for every year since the Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain. He and his wife, Janet, raise their glasses in a toast to “the faithful” one last time.

Even then we have a hard time believing it’s over. That we are giving in after all this time. That we’re not fighting through

thickanthin

after all.

“Everyone that asketh receiveth; and he that seeketh findeth.”

We lost, they found.

Our-men.

Independence, coming

readyornot.

In March 1978, Bishop Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa of the African National Council makes an agreement with the white government and forms an interim government, which combines the weakest of the African political parties with the most determined of the old white guard and in June 1979 he wins elections, which may or may not have been free and fair (depending on who you are, and the color of your skin). We buy T-shirts to replace our old rhodesia is super T-shirts. These new T-shirts read zimbabwe-rhodesia is super and we say, “Especially Rhodesia.” But the War carries on and more and more people die and the fight is fiercer and more angry than before. And the Africans have splintered into political groups and tribal factions and fight one another, on top of also fighting the whites.

So Muzorewa, who is (after all) a Christian man and a Methodist, does a most un-African thing. He gives up power after only six months. He hands Zimbabwe-Rhodesia and the whole damned mess back to the British. In London, December 1979, it is decided that once again we are a British colony except this time, the British mean to give us independence under majority rule. None of this mix-and-match, pick-your-own-muntu style of Rhodesian government.

There is a cease-fire and we have to take Dad’s FN rifle and Mum’s Uzi and all Dad’s army-issue camouflage to the police station. We keep the rat packs and eat the last of the pink-coated peanuts and stale Cowboy bubble gum and we dissolve and drink the last of the gluey coffee paste. The policeman who collects the guns writes our name in a book and apologizes, “I’m sorry, hey.” He doesn’t say what he is sorry for.

There are

freeanfair

elections in February 1980, just before my eleventh birthday, and we lose the elections. By which I mean our

muntu,

Bishop Muzorewa, is soundly defeated. He wins three paltry seats. One man, one vote. We’re out.

On April 18, 1980, Robert Gabriel Mugabe takes power as Zimbabwe’s first prime minister. I have never even heard of him. The name “Rhodesia” is dropped from “Zimbabwe-Rhodesia.” Now our country is simply “Zimbabwe.”

Zimba dza mabwe.

Houses of stone.

Those who live in stone houses shouldn’t throw stones for fear of ricochet.

The first to go are the Afrikaans children.

The day Robert Gabriel Mugabe wins the elections the Afrikaans parents drive up to the school, making a long snake of cars like a funeral procession, to collect their kids. The kids, fists held tightly by stern-bosomed mothers, are taken to their dormitories, where we are not ordinarily allowed until five o’clock bath time. The matrons have to get the maids to bring stacks of trunks down from the trunk room. The Afrikaans mothers pack. The Afrikaans fathers stay in the car park, leaning against their cars, smoking and talking quietly to each other in Afrikaans. There is a sense of history in their carriage;

we’ve done this before and we’ll do it again.

We have learned about the Great Trek in school.

The “Groot Trek” of 1835, when more than ten thousand Boers, the Voortrekkers, left the Cape Colony and came north. They left the paradise of the Cape because they were fighting with their Xhosa neighbors and because they were dissatisfied with the English colonial authorities, who had forbidden the slave trade and who believed in equality between whites and nonwhites. So many men, women, and children died during the Great Trek, their bodies draped gorily over wagon wheels and under wagon wheels and next to horses in the illustrations in our history books. They died because they believed that the British policy of Emancipation destroyed their social order, which was based on separation of the races. They saw white predominance as God’s own will.

So, now the Little Trek.

But the next day some of the English Rhodesians are driven away too. There is only a handful of us left at supper that night; no more than twenty children in a dining room designed to hold ten times as many. My sister has already moved from Chancellor Junior School to the Umtali Girls’ High School. So she is not around for me to ask, “Where are Mum and Dad?”

Tomorrow, the children who have gone to “B” schools, for coloureds and Indians, will be here. The children from “C” schools, for blacks, will be here too. Tomorrow, children who have never been to school, never used a flush toilet, never eaten with a knife and fork, will arrive. They will be smelling of wood smoke from their hut fires.

Tomorrow child soldiers will arrive. They can track their way through the night-African bush by the light of the stars, these

mujiba

and

chimwido

. They are worldly and old and have fixed, long-distance stares.

Eating with your mouth closed and using a knife and fork properly can’t save your life.

It only takes a minute to learn how to flush a toilet.

But still Mum and Dad don’t come and fetch me away.

Instead, the first black child is brought to the school. We watch in amazement as he is helped out of a car—a proper car like Europeans drive—by his mother, who is more beautifully dressed than my mother ever is. She smiles as she leads her son, confidently, head held high, one high-heeled foot clacking smartly past the next high-heeled foot, through the tunnel that leads around the sandbags and into the boys’ dormitory.

We won’t be needing those sandbags anymore.

This woman is not a

muntu

nanny. This child is not a picanin. He is beautifully dressed in a brand-new uniform. The uniform is not a worn and stained hand-me-down like the one I wear.

We wait until the mother and father of this little black child drive away, spinning up gravel from the back wheels of their white-people’s car as they leave. And then we make a circle around the little black boy. The boy tells us he is called Oliver Chiweshe.

I have not known the full name of a single African until now. Oliver Chiweshe. Until now I only knew Africans by their Christian names: Cephas, Douglas, Loveness, Violet, Cloud, July, Flywell. I am learning that Africans, too, have full names. And not only do Africans have full names, but their names can be fuller than ours. I try and get my tongue around Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo; Robert Gabriel Mugabe; the Reverend Canaan Sodindo Banana; Bishop Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa: these are the names of our new leaders.

I say, “That’s a nice name.”

“Actually, my full name is Oliver Tendai Chiweshe,” says Oliver, emphasizing his middle name. He speaks beautifully accented, perfect English.

We say, “Was that your father who dropped you off?”

Oliver looks at us with pity. “That was my driver,” he tells us, “and my maid.” He pauses and says, “Daddy is in South Africa this week.”

We are stunned by this news. “Why?”

“Business,” says Oliver complacently.

“And then he’ll come back?”

“Ja,”

says Oliver.

That night at supper, Oliver sits alone. None of us will sit next to him. We wait to see if he eats like a

muntu.

We wait to see if he cement-mixes. But he has perfect European manners, which are quite different from perfect Mashona manners. He takes small, polite bites. He puts his knife and fork down on the edge of his plate between mouthfuls. He sips his water modestly. At the end of his meal, he pats the top of his lip with his napkin and puts his knife and fork together.

I turn to my neighbor and hiss, “I hope I don’t get

that

napkin when it comes back from laundry.”

“

Ja,

me too, hey.”

Within one term, there are three white girls and two white boys left in the boardinghouse. We are among two hundred African children who speak to one another in Shona—a language we don’t understand—who play games that exclude us, who don’t have to listen to a word we say.

Then our white matron leaves and a young black woman comes to take her place. She is pretty and firm and kind. She does not smoke cigarettes and drink cheap African sherry in her room after lights-out. She redecorates the matron’s sitting room with a white cloth over the back of the worn old sofa and fresh flowers on the coffee table, and she gets rid of all the ashtrays. A sign goes up on the door of her sitting room: no smoking please. young lungs growing.

Some of the new children in the boardinghouse are much older than we, fourteen at least. They already have their periods, they have boyfriends. They laugh at my pigeon-flat chest.

We sleep so close that, even with the lights out, I can make out the shape of my neighbor’s body under the thin government-issue blanket. I watch the way she sleeps, rolled onto her side, too womanly for the slender child’s bed. Her name is Helen. Her warm breath reaches my face.

Helen, Katie, Do It, Fiona, Margaret, Mary, Kumberai.

Some of the children at my school are the children of well-known guerrilla fighters. We have the Zvobgo twin sisters for instance, whose father, Eddison, spent seven years in jail during the War for “political activism.” He is a war hero now and very famous; he is in the new government.

There are, it turns out, no white war heroes. None of the army guys for whom I cheered and prayed will be buried at Heroes Acre under the eternal flame. They will not have their bones dug up from faraway battlefields and driven in stately fashion all the way to Harare for reburial.

We eat elbow to elbow. We brush our teeth next to each other, leaning over shared sinks, our spit mixing together in a toothpaste rainbow of blue and green and white. We shit next to each other in the small, thin-walled booths.

That year, there is a water shortage and we have to conserve water.

Now we must pee on top of each other’s pee. One cup of water each every day with which we must brush our teeth and wash our faces in the morning. We have to share bathwater. I am reluctant. Then the new, black matron says, “Come on, stop this silly nonsense. Skin is skin. In you get.”

While our new matron watches, I climb into the bathwater, lukewarm with the floating skin cells of Margaret and Mary Zvogbo. Nothing happens. I bathe, I dry myself. I do not break out in spots or a rash. I do not turn black.

The year I turn twelve, Mum and Dad drive me to Harare, where I write an entrance examination to get into a prestigious, girls-only private high school, and much to everyone’s surprise I pass the examination and am accepted into Arundel High School, known by its past and current inmates as the Pink Prison.