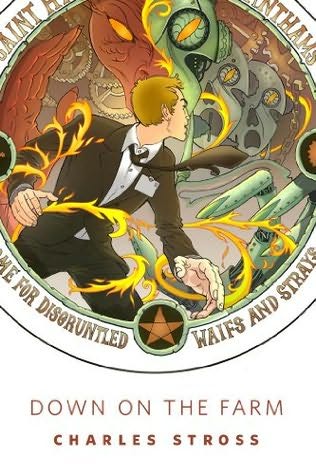

Down on the Farm

Authors: Charles Stross

Ah, the joy of summer: here in the south-east of England it’s the season of mosquitoes, sunburn, and water shortages. I’m a city boy, so you can add stifling pollution to the list as a million outwardly mobile families start their Chelsea tractors and race to their holiday camps. And that’s before we consider the hellish environs of the Tube (far more literally hellish than anyone realizes, unless they’ve looked at a Transport for London journey planner and recognized the recondite geometry underlying the superimposed sigils of the underground map).

But I digress...

One morning, my deputy head of department wanders into my office. It’s a cramped office, and I’m busy practicing my Frisbee throw with a stack of beer mats and a dart-board decorated with various cabinet ministers. “Bob,” Andy pauses to pluck a moist cardboard square out of the air as I sit up, guiltily: “a job’s just come up that you might like to look at—I think it’s right up your street.”

The first law of Bureaucracy is,

show no curiosity outside your cubicle

. It’s like the first rule of every army that’s ever bashed a square:

never volunteer

.

If you ask questions (or volunteer) it will be taken as a sign of inactivity, and the devil, in the person of your line manager (or your sergeant) will find a task for your idle hands. What’s more, you’d better believe it’ll be less appealing than whatever you were doing before (creatively idling, for instance), because inactivity is a crime against organization and must be punished. It goes double here in the Laundry, that branch of the British secret state tasked with defending the realm from the scum of the multiverse, using the tools of applied computational demonology: volunteer for the wrong job and you can end up with soul-sucking horrors from beyond spacetime using your brain for a midnight snack. But I don’t think I could get away with feigning overwork right now, and besides: he’s packaged it up as a mystery. Andy knows how to bait my hook, damn it.

“What kind of job?”

“There’s something odd going on down at the Funny Farm.” He gives a weird little chuckle. “The trouble is going to be telling whether it’s just the usual, or a more serious deviation. Normally I’d ask Boris to check it out but he’s not available this month. It has to be an SSO 2 or higher, and I can’t go out there myself. So...how about it?”

Call me impetuous (not to mention a little bored) but I’m not stupid. And while I’m far enough down the management ladder that I have to squint to see daylight, I’m an SSO 3, which means I can sign off on petty cash authorizations up to the price of a pencil and get to sit in on interminable meetings, when I’m not tackling supernatural incursions or grappling with the eerie, eldritch horrors in Human Resources. I even get to represent my department on international liaison junkets, when I don’t dodge fast enough. “Not so quick—why can’t you go? Have you got a meeting scheduled, or something?” Most likely it’s a five course lunch with his opposite number from the Dustbin liaison committee, knowing Andy, but if so, and if I take the job, that’s all for the good: he’ll end up owing me.

Andy pulls a face. “It’s not the usual. I

would

go, but they might not let me out again.”

Huh

? “‘They’? Who are ‘they’?”

“The Nurses.” He looks me up and down as if he’s never seen me before. Weird. What’s gotten into him? “They’re sensitive to the stench of magic. It’s okay for you, you’ve only been working here, what? Six years? All you need to do is turn your pockets inside out before you go, and make sure you’re not carrying any gizmos, electronic or otherwise. But I’ve been here coming up on fifteen years. And the longer you’ve been in the Laundry...it gets under your skin. Visiting the Funny Farm isn’t a job for an old hand, Bob. It has to be someone new and fresh, who isn’t likely to attract their professional attention.”

Call me slow, but finally I figure out what this is about. Andy wants me to go because he’s

afraid

.

(See, I told you the rules, didn’t I?)

* * *

Anyway, that’s why, less than a week later, I am admitted to a Lunatickal Asylum—for that is what the gothic engraving on the stone Victorian workhouse lintel assures me it is. Luckily mine is not an emergency admission: but you can never be too sure...

* * *

The old saw that there are some things that mortal men were not meant to know cuts deep in my line of work. Laundry staff—the Laundry is what we call the organization, not a description of what it does—are sometimes exposed to mind-blasting horrors in the course of our business. I’m not just talking about the usual PowerPoint presentations and self-assessment sessions to which any bureaucracy is prone: they’re more like the mythical Worse Things that happen at Sea (especially in the vicinity of drowned alien cities occupied by tentacled terrors). When one of our number needs psychiatric care, they’re not going to get it in a normal hospital, or via care in the community: we don’t want agents babbling classified secrets in public, even in the relatively safe confines of a padded cell. Perforce, we take care of our own.

I’m not going to tell you what town the Funny Farm is embedded in. Like many of our establishments it’s a building of a certain age, confiscated by the government during the Second World War and not returned to its former owners. It’s hard to find; it sits in the middle of a triangle of grubby shopping streets that have seen better days, and every building that backs onto it sports a high, windowless, brick wall. All but one: if you enter a small grocery store, walk through the stock room into the back yard, then unlatch a nondescript wooden gate and walk down a gloomy, soot-stained alley, you’ll find a dank alleyway. You won’t do this without authorization—it’s protected by wards powerful enough to cause projectile vomiting in would-be burglars—but if you did, and if you followed the alley, you’d come to a heavy green wooden door surrounded by narrow windows with black-painted cast-iron bars. A dull, pitted plaque next to the doorbell proclaims it to be St Hilda of Grantham’s Home For Disgruntled Waifs And Strays. (Except that most of them aren’t so much disgruntled as demonically possessed when they arrive at these gates.)

It smells faintly of boiled cabbage and existential despair. I take a deep breath and yank the bell-pull.

Nothing happens, of course. I phoned ahead to make an appointment, but even so, someone’s got to unlock a bunch of doors and then lock them again before they can get to the entrance and let me in. “They take security seriously there,” Andy told me—“can’t risk some of the battier inmates getting loose, you know.”

“Just how dangerous are they?” I’d asked.

“Mostly they’re harmless—to other people.” He shuddered. “But the secure ward—don’t try and go there on your own. Not that the Sisters will let you, but I mean, don’t even

think

about trying it. Some of them are...well, we owe them a duty of care and a debt of honour, they fell in the line of duty and all that, but that’s scant consolation for you if a senior operations officer who’s succumbed to paranoid schizophrenia decides that you’re a BLUE HADES and gets hold of some red chalk and a hypodermic needle before your next visit, hmm?”

The thing is, magic is a branch of applied mathematics, and the inmates here are not only mad: they’re computer science graduates. That’s why they came to the attention of the Laundry in the first place, and it’s also why they ultimately ended up in the Farm, where we can keep them away from sharp pointy things and diagrams with the wrong sort of angles. But it’s difficult to make sure they’re safe. You can solve theorems with a blackboard if you have to, after all, or in your head, if you dare. Green crayon on the walls of a padded cell takes on a whole different level of menace in the Funny Farm: in fact, many of the inmates aren’t allowed writing implements, and blank paper is carefully controlled—never mind electronic devices of any kind.

I’m mulling over these grim thoughts when there’s a loud

clunk

from the door, and a panel just large enough to admit one person opens inward. “Mr Howard? I’m Dr. Renfield. You’re not carrying any electronic or electrical items or professional implements, fetishes, or charms?” I shake my head. “Good. If you’d like to come this way, please?”

Renfield is a mild-looking woman, slightly mousy in a tweed skirt and white lab coat, with the perpetually harried expression of someone who has a full Filofax and hasn’t worked out yet that her watch is losing an hour a day. I hurry along behind her, trying to guess her age.

Thirty five? Forty five

? I give up. “How many inmates do you have, exactly?” I ask.

We come to a portcullis-like door and she pauses, fumbling with an implausibly large key ring. “Eighteen, at last count,” she says. “Come on, we don’t want to annoy Matron. She doesn’t like people obstructing the corridors.” There are steel rails recessed into the floor, like a diminutive narrow-gauge railway. The corridor walls are painted institutional cream, and I notice after a moment that the light is coming through windows set high up in the walls: odd-looking devices like armoured-glass chandeliers hang from pipes, just out of reach. “Gas lamps,” Renfield says abruptly. I twitch. She’s noticed my surreptitious inspection. “We can’t use electric ones, except for Matron, of course. Come into my office, I’ll fill you in.”

We go through another door—oak, darkened with age, looking more like it belongs in a stately home than a Lunatick Asylum, except for the two prominent locks—and suddenly we’re in mahogany row: thick wool carpets, brass door-knobs,

light switches

, and over-stuffed armchairs. (Okay, so the carpet is faded with age and transected by more of the parallel rails. But it’s still Officer Country.) Renfield’s office opens off one side of this reception area, and at the other end I see closed doors and a staircase leading up to another floor. “This is the administrative wing,” she explains as she opens her door. “Tea or coffee?”

“Coffee, thanks,” I say, sinking into a leather-encrusted armchair that probably dates to the last but one century. Renfield nods and pulls a discreet cord by the door frame, then drags her office chair out from behind her desk. I can’t help noticing that not only does she not have a computer, but her desk is dominated by a huge and ancient manual typewriter—an Imperial Aristocrat ‘66’ with the wide carriage upgrade and adjustable tabulator, I guess, although I’m not really an expert on office appliances that are twice as old as I am—and one wall is covered in wooden filing cabinets. There might be as much as thirty megabytes of data stored in them. “You do everything on paper, I understand?”

“That’s right.” She nods, serious-faced. “Too many of our clients aren’t safe around modern electronics. We even have to be careful what games we let them play—Lego and Meccano are completely banned, obviously, and there was a nasty incident involving a game of Cluedo, back before my time: any board game that has a non-deterministic set of rules can be dangerous in the wrong set of hands.”

The door opens. “Tea for two,” says Renfield. I look round, expecting an orderly, and freeze. “Mr Howard, this is Nurse Gearbox,” she adds. “Nurse Gearbox, this is Mr Howard. He is

not

a new admission,” she says hastily, as the thing in the doorway swivels its head towards me with a menacing hiss of hydraulics.

Whirr-clunk

. “Miss-TER How-ARD. Wel-COME to“—

ching

—“Sunt-HIL-dah’s“—

hiss-clank

. The thing in the very old-fashioned nurse’s uniform—old enough that its origins as a nineteenth-century nun’s habit are clear—regards me with unblinking panopticon lenses. Where its nose should be, something like a witch-finder’s wand points towards me, stellate and articulated: its face is a brass death mask, mouth a metal grille that seems to grimace at me in pointed distaste.

“Nurse Gearbox is one of our eight Sisters,” explains Dr Renfield. “They’re not fully autonomous“—I can see a rope-thick bundle of cables trailing from under the hem of the Sister’s floor-length skirt, which presumably conceals something other than legs—“but controlled by Matron, who lives in the two sub-basement levels under the administration block. Matron started life as an IBM 1602 mainframe, back in the day, with a summoning pentacle and a trapped class four lesser nameless manifestation constrained to provide the higher cognitive functions.”

I twitch. “It’s a grid, please, not a pentacle. Um. Matron is electrically powered?”

“Yes, Mr. Howard: we allow electrical equipment in Matron’s basement as well as here in the staff suite. Only the areas accessible to the patients have to be kept power-free. The Sisters are fully equipped to control unseemly outbursts, pacify the over-stimulated, and conduct basic patient care tasks. They also have Vohlman-Flesch Thaumaturgic Thixometers for detecting when patients are in danger of doing themselves a mischief, so I would caution you to keep any occult activities to a minimum in their presence—despite their hydraulic delay line controls, their reflexes are

very

fast.”

Gulp

. I nod appreciatively. “When was the system built?”

The set of Dr. Renfield’s jaw tells me that she’s bored with the subject, or doesn’t want to go there for some reason. “That will be all, Sister.” The door closes, as if on oiled hinges. She waits for a moment, head cocked as if listening for something, then she relaxes. The change is remarkable: from stressed-out psychiatrist to tired housewife in zero seconds flat. She smiles tiredly. “Sorry about that. There are some things you really shouldn’t talk about in front of the Sisters: among other things, Matron is very touchy about how long she’s been here, and everything

they

hear,

she

hears.”