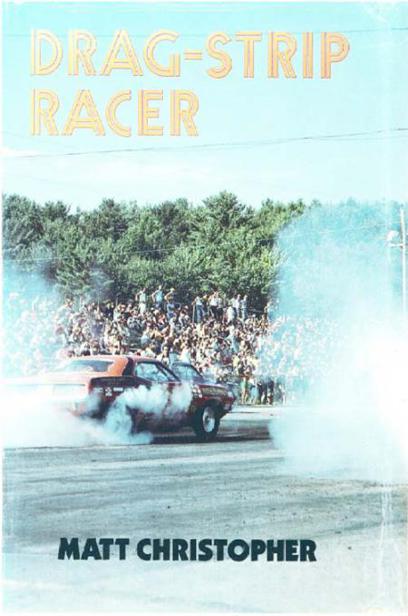

Drag-Strip Racer

Authors: Matt Christopher

Sports Stories

The Lucky Baseball Bat

Baseball Pals

Basketball Sparkplug

Little Lefty

Touchdown for Tommy

Break for the Basket

Baseball Flyhawk

Catcher with a Glass Arm

The Counterfeit Tackle

Miracle at the Plate

The Year Mom Won the Pennant

The Basket Counts

Catch That Pass!

Shortstop from Tokyo

Jackrabbit Goalie

The Fox Steals Home

Johnny Long Legs

Look Who’s Playing First Base

Tough to Tackle The Kid Who Only Hit Homers

Face-Off

Mystery Coach

Ice Magic

No Arm in Left Field

Jinx Glove

Front Court Hex

The Team That Stopped Moving

Glue Fingers

The Pigeon with the Tennis Elbow

The Submarine Pitch

Power Play

Football Fugitive

Johnny No Hit

Soccer Halfback

Diamond Champs

Dirt Bike Racer

The Twenty-One-Mile Swim

The Dog That Stole Football Plays

Run, Billy, Run

Wild Pitch

Tight End

Drag-Strip Racer

Animal Stories

Desperate Search

Stranded

Earthquake

Devil Pony

COPYRIGHT

© 1982

BY MATTHEW F. CHRISTOPHER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL MEANS INCLUDING

INFORMATION STORAGE AND RETRIEVAL SYSTEMS WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER, EXCEPT BY A REVIEWER WHO MAY QUOTE

BRIEF PASSAGES IN A REVIEW.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: December 2009

ISBN: 978-0-316-09553-2

Contents

To Carl, Bruce, and Bradley

T

HE EARLY MORNING

silence was heavy II in the Ford pickup as it traveled at a steady forty-five-mile-per-hour clip on Route 60 to Candlewyck

Speedway. The stillness was broken only by the rhythmic sound of the motor and the

thump-thump

of the tires crossing the tarpatched stripes on the highway.

Behind the wheel, sixteen-year-old Ken Oberlin glanced at his sister, Janet, sitting beside him. “Excited?”

“Yes.”

“I’m glad,” he said. “You and Lori are the only ones on my side. Neither Mom or Dad is keen about my drag racing. But Uncle

Louis left Li’l Red to me, so what am I supposed to do? Toss her on a junk pile?”

Janet looked at him, her coffee-brown eyes

shining. “Well, they

did

let you drive it in auto-crosses,” she said. At fourteen she had taken an interest in cars herself, although she still had

two years to go before she could get a driver’s license.

“Yes, and I’m glad I did,” he told her. “But autocrosses are mainly for precision and skill. I think I learned a lot, but

what I’m interested in now is speed. Boy, I wish Uncle Louis hadn’t died. I mean, if he was just around to give me a little

advice now and then.”

Uncle Louis was his father’s brother, a drag-strip freak from his teenage years to the day he passed away of a heart attack

at age fifty-nine.

Ken thought back to the times his uncle had taken him for rides in Li’l Red, times he’d seen her blazing down the 1320-foot

asphalt strip to more victories than he could remember. They were glorious memories.

“What does Dana think about it?” Janet asked.

“I don’t care what he thinks,” Ken said stiffly. “He’s got his motorcycle, I’ve got my car.”

He’d never forget the cold stare his brother had given him when the words of Uncle Louis’s will were read by his attorney:

I bequeath my racer, Li’l Red, to my nephew Kenneth, who I hope will enjoy racing it with all the pleasure that it has given

me.

Sometimes he wondered if Dana was really a member of their family. The guy had left school a month before he was supposed

to graduate, telling the family he was positive he wouldn’t pass the final exams anyway. Now he worked part time at Nick Evans’s

pool parlor, and from the money he earned had managed to buy himself a Kawasaki motorcycle.

“How much farther do we have to go?” Janet asked, as she looked down the gleaming white road. It was flanked on either side

by brush and pasture fields. A couple of dozen cattle grazed monotonously.

“About two, maybe three miles,” Ken said.

Minutes later they could see the towering sign in the distance: Candlewyck Speedway. Soon Ken changed to the right-turn-only

lane, reached the intersection, and turned through an open gate. He paused at the ticket office, showed his pre-entry card

to a red-haired woman working there, drove through another gate, and turned left toward the technical inspection station.

He showed the card again to one of three guys in white coveralls with “Inspector” labels sewn on the left sides of their chests.

Then he got out of the pickup, unlocked the chain securing the racer, lowered the ramp, and drove the red Chevy off

the trailer and onto a weighing scale. He emerged from it to permit the men to continue their inspection of the car’s height,

engine size, tires, and carburetor. The men made check marks on their tablets, then—about fifteen minutes later—stepped back

and told Ken he was set to run. Over a walkie-talkie one of the men informed the timing tower that “a red 1975 Chevy owned

and driven by Ken Oberlin has passed inspection and is coming in for its trial runs.”

“Is it necessary to go through this full inspection every day?” Ken asked the man.

“No. There’ll be just a quick check once a week after this, unless you don’t show up for two or three weeks,” the tech man

told him, smiling.

“Thanks.”

Ken drove the Chevy back on the trailer, then drove the trailer to the pit stop, a long vacant lot facing the track, and saw

an ambulance along with three other trucks and trailers there. The owners of the trucks and trailers were on the lanes, trial-running

their cars.

Ken felt a rush of excitement as he parked, shut off the engine, and watched the trial runs. The three cars present were an

orange Omni, a yellow Vega, and a blue Camaro, each emblazoned on the side with the driver’s name and the commercial

outfit sponsoring him. Having a commercial company behind you wasn’t necessary, but it helped when it came to paying for

supplies and repairs. Ken, aware of the tightness of money in his household, hoped to find a sponsor soon.

“You going to sit here all day?” Janet said suddenly, glancing casually at him.

Ken looked at her and smiled. He got out, walked back to the trailer, and lowered the ramp againto drive Li’l Red off.

Soon he was back inside the two-door Chevy that was powered by a 1970, 396-horsepower big block engine Uncle Louis had installed

himself. He started the car, backed it up, and let it idle while he climbed out to take his firesuit, helmet, and gloves from

a duffel bag and put them on.

He glanced up at the top windows of the dome-shaped tower building and thought he saw one of the track co-owners—either Buck

Morrison or Jay Wells—looking out at him.

A moment later a voice boomed over a loudspeaker: “Ken Oberlin, drive around the timing tower and get ready to run against

the Camaro. Take number one lane, please. You have three trial runs. Your best time will be used to determine your run for

this afternoon’s Eliminator contest.”

Ken acknowledged the order by raising a hand; then he drove around the tower toward lane one and stopped as a crewman standing

on the lanes behind the two cars that were ready to run raised his hand. A moment later the blue Camaro drove up and stopped

beside him, ready to get on lane two.

Ken glanced at the driver—Bill Robbins, according to the name blazing in white across the door. Robbins turned to him and

raised a thumb, and Ken acknowledged the sign by raising his.

He knew very few drivers personally. He had trial-run his car only twice before to get the feel of its power and performance.

This morning was the first time he was going to trial-run it to qualify for drag racing. It was going to be the Big Event

for him, the start of something great. Maybe.

Yeah, maybe, he told himself. Even Uncle Louis had never won the Winternationals, the Gatornationals, or any other national

event. But he’d been close to it a dozen times. And he’d made a name for himself in the world of Pro Stock racing.

They got the signal to move ahead. Ken moved the gear lever, jammed his foot on the gas pedal, and felt the slicks take a

solid grip of the rosin-topped asphalt as the car shot forward. Then he

slammed on the brakes, paused a moment, and repeated the procedure. Satisfied that the tires were doing their job, he drove

up to the staging lane and braked when the top yellow light of the “Christmas tree,” about twenty feet down the course, flashed

on.

It was hot inside the car. Sweat dripped from his forehead into his eyes, blurring his vision. He lifted the plastic shield

of his helmet and wiped his eyes with the tip of his gloved finger, then waited for the staged lights of the Christmas tree

to be activated.

Suddenly they were, and he glued his attention on them; every muscle in his body responded with tension as, one by one, the

amber lights turned on. Only two and a half seconds elapsed from the time the lights turned on till the green starting light

activated. Take off too soon and a red light flashed, indicating a foul start and an automatic loss. Take off too late and

you might as well forget it. Most races were won or lost at the starting line, so it paid to concentrate one hundred percent

on the lights.

There! The last amber light went on, then the green—and Ken jammed on the gas pedal. He felt his body thrust back against

the seat as the car sprang forward, the front end tilting up on its

frame for a second or two, then settling back down. All of her 396 horsepower responded as a unit. Ken’s hand on the five-speed

stick shift was white-knuckled and trembled under the severe strain of the screaming transmission. He braced his teeth as

he felt his skin draw back against his jaw. He shifted into the next gear, the 4¾-inch travel from one gear to the next feeling

liquid smooth.

The car blazed down the track, engine roaring. The best Ken had done so far in Li’l Red was 12.08 at 112.67 miles per hour.

He was sure the car could do better. She had the power harnessed inside that metal body. Uncle Louis had learned to use it

to her upper limits. I should, too, Ken told himself.

He reached the end of the quarter-mile run and stepped on the brakes. The car slowed briefly, then something seemed to spring

loose and the car continued its swift speed down the lane.

Stunned and gripped with fear, Ken kept pumping the brake pedal. But the brakes still didn’t respond. Oh, no, he thought,

what happened to the brakes?

Then he felt the car pull to the right. It was traveling so fast he was off the lane before he knew it. He had a blurred glimpse

of the Camaro

beside him, and, in an effort to avoid a collision with it, he swung the wheel to the left. The momentum of the car’s speed

carried him across the lane toward the guardrail. He turned the wheel to the right to avoid hitting it, but struck it with

the side of his left front fender. At the same time he felt a jarring pain in his left foot, which he had braced against the

floorboard.

He veered back onto the asphalt and headed toward the metal fence in the distance, shoving the shift lever into lower speeds

now to slow the car down. Some fifty feet from the fence he made a U-turn and brought the vehicle to a stop, nose pointing

toward the pit stops.

He yanked off his helmet, gripped the wheel, and shut his eyes in angry despair.

“What happened?” he cried aloud. “What could have happened?”

He felt the pain in his left ankle again, and wondered if it were sprained or broken. He probably would have to have it x-rayed

to make sure. What lousy luck.

He heard a siren screaming in the distance, drawing nearer by the second.