Dragon Bones (23 page)

Authors: Lisa See

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Thrillers, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Women Sleuths

Hulan listened, and David pressed his advantage. “I’m not going to tell you it isn’t strange that Tang Wenting is here, because it is. I’m not going to tell you that the group is completely harmless, because the hostility in the cave was scary, but it had to do with all of the terrible things these people are dealing with—moving, uncertainty, feeling powerless. And I’m certainly not going to tell you that I support everything the Society advocates, but you know as well as I do that people ought to have the right to practice their religion.”

“Even if that means making threats against the dam? Wu Peng said his son was going to stop it.”

“Wu Huadong was a peasant living in abject poverty. How exactly was he going to stop the dam?”

“I don’t know, but I’m going to the dam tomorrow to find out.”

“You’re way off track. We never should have gone to that meeting—”

“Why can’t you respect my opinion?” she asked. “You said we should see what other facts came in. Now that they have, you’re choosing to ignore their implications.”

“That’s not true,” he said in exasperation. “I’m trying to keep us focused on our assignments. You’re investigating what are now two deaths. I’m supposed to be looking into these thefts—”

“To me, those things are minor compared with seeing Tang Wenting in that cave! He said he’d make me pay for what happened in Beijing, and now he’s here!”

“His presence in Bashan doesn’t necessarily make him vengeful or dangerous. Yes, he threatened you in the heat of a terrible and emotional moment, but he may just be making his regular rounds to chapters in the countryside. And remember, he tried to stop the woman in the square from cutting off her daughter’s hand….” He held back the rest—that Hulan’s solution had resulted in death.

This argument was moving into perilous territory. He took a deep breath and started over. “Two people have died here in Bashan. You need to table your campaign against this religion for now and solve Brian’s and Lily’s murders.”

“It’s not a religion. It’s a cult,” she muttered.

“Call it whatever you want, Hulan,” he said, his frustration rising again, “but we both know you’re using it as a barrier—”

“Xiao Da is using religion to control the group in a political way. He’s teaching people to mutilate—”

“Where do you get that?”

“The mother on the square,” she answered. In response to his look, she added defensively, “Well, you brought it up.”

“You said yourself she was crazy.”

“Then what about Brian and Lily?”

“They were branded.

That’s

what you should be looking at. What does that brand mean to the killer?”

“You don’t understand!”

“Then help me.”

They had stopped again. They were wet, muddy, and standing on one of the most barren tracts of land David had ever seen.

“I killed that woman.” Hulan’s voice was tired. “In the square. I’m the mother killer. If I’d followed my instincts then, she’d still be alive.”

“Oh, honey, that has nothing to do with this.”

“And if I’d followed my instincts when we got here, then Lily would still be alive too.”

“You can’t blame yourself.”

“Of course I can.”

Even in the dark he could see she was trembling. This wasn’t about Xiao Da, Tang Wenting, or the All-Patriotic Society anymore, nor was it about Lily or the woman in the square. It was about Chaowen. David had longed for this conversation for months, but he had never anticipated that it would come in the middle of an argument.

“There was nothing we could do,” he said softly, trying to rein in his anger of moments before.

“I was her mother!”

“You’ve got to stop punishing yourself.”

“I can’t.”

She wanted to say something more, and he gently coaxed her. “What is it?”

“You should have done something,” she said at last.

“What, Hulan?” he asked in anguish. “What could I have done?”

“You should have made us move to the States. She might never have gotten sick, and if she had, she would have gotten proper medical care….”

He heard what she said as an unfair, cruel, and false accusation. He was the one who had wanted Chaowen to be born in the United States; he’d wanted her to grow up there. It was Hulan who had refused to leave China—over many years and many requests. It was she who had insisted they not take Chaowen to the hospital “just yet.” Some Tylenol would do, Hulan had claimed. And then it was she who had emotionally deserted David, leaving him to mourn his bright and beautiful daughter alone.

“If going to Los Angeles would have saved our daughter’s life, then you are to blame,” he retorted without thinking. “Just as you’re to blame for not wanting to go to the hospital sooner.”

Finally she’d gotten him to say what they’d both been censoring all these months. Hulan didn’t say a word. She just turned away from him and began walking toward Bashan.

They were soaked to the skin by the time they got back to town. David took a hot shower and got into bed, then watched as Hulan, wearing a white silk wrap that was sheer enough to hint at her nakedness underneath, called Beijing and left a voice message for Vice Minister Zai outlining their travel plans as well as what she’d discovered about the cult: the group appeared to be advocating violence, a high-ranking All-Patriotic Society lieutenant was in Bashan, Xiao Da himself might be here too, and the MPS should send a team to make arrests at one of the nightly meetings in the cave as soon as possible. After hanging up, she gathered a few things to take with her tomorrow. Then she opened the window to its widest. Warm, moist air followed her to the bed. She sat on the edge of the mattress and looked at him squarely.

They were way past apologies, and she spoke with chilling matter-of-factness. “Tomorrow you and Pathologist Fong will drop me at the dam so I can ask Stuart Miller about what we heard tonight and find out more about his relationships with Brian and Lily. You and Fong can continue on to Wuhan airport. He’ll catch his flight to Beijing, and you can fly to Hong Kong for the auction.”

She turned off the light and curled on her side away from him. He lay there listening to the whirring of the overhead fan. Once he thought she was asleep, he got up, dressed, slipped out into the corridor, and walked to the veranda outside the restaurant. He sat in a wicker chair and watched as the downpour tapered off to heavy mist.

David was in deep despair. He’d loved Hulan for so many years, even those when she’d been lost to him. He’d believed theirs was a true love, but tonight—after everything that had happened today—when he heard her self-reproach for what seemed the millionth time, he’d let down his guard and lost his patience. He’d personally given up much to have a family life in China. He’d abandoned his love of the great issues of law and justice, settling instead for small cases of little significance. (Looking for a few stolen artifacts in a small town in China’s interior was a far cry from the international disputes he’d handled before.) It was a choice he’d willingly made so that the three of them could be happy.

David didn’t hate Hulan for what had happened to Chaowen. Hulan had done what any mother would have done in the same circumstances. An hour or a day wouldn’t have made any difference; the meningitis strain was too virulent, and Chaowen could have contracted it anywhere. But when David heard Hulan blame him for Chaowen’s death, he’d cracked. In that moment he’d finally faced what had been before him these past months. Hulan might never get past the what-ifs. She might look at him forever with eyes as empty as if a curtain had fallen over her soul. He’d thought she was lost and he could save her. What he hadn’t understood was that that same blanket had covered him. He was lost, too—in his career, in his spirit, and in his marriage. He loved Hulan with all of his heart, but if there was to be redemption for either of them, she would have to reach out to him.

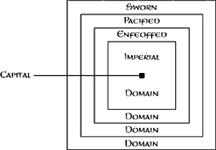

THE SWORN DOMAIN

(Yao Fu)

Remoter still. Within the first 300

li

are allied barbarians and people of restraint. The last 200

li

are saved for criminals undergoing lesser banishment.

THE HELICOPTER SWOOPED DOWN FOR A CLOSER VIEW OF A

particularly dramatic outcropping of rocks and verdant foliage in the Xiling Gorge. David sat up front with the pilot, Hulan was in the backseat with Fong, and Lily’s body was shrouded on one of the helicopter’s pontoons. Pregnant clouds hung heavily over the lofty, pine-covered summits. Down below, the swollen river swaggered past villages and towns, terraced fields and honeycombed rocks.

The rotors made a sickly racket as the pilot tried his best to maintain altitude. When the helicopter took a particularly nasty dip in an air current, Pathologist Fong, who yesterday had minced no words in his description of his trip in this same antiquated bird, looked over at Hulan with an expression that said, I told you so. Fong turned his attention back to the river below. The pilot had only two pairs of earphones, so he was giving the pathologist his promised tour. This left David and Hulan to experience the deafening sounds of the rotors and motor, which was probably a good thing. At least they had an excuse not to speak to each other.

She’d heard him leave their room last night. She’d heard him come back just before dawn. They’d grabbed a quick bite in the dining room with Fong, and at seven the three of them had met the helicopter in a little clearing just west of Bashan. David hadn’t said ten words to her in that time.

Ahead of them lay the dam site. What had once been the sleepy fishing village of Sandouping was now a vast blight on the landscape. Huge chunks of land had been bitten out of the earth so that part of the site looked like a strip mine. The other part was the massive wall of the dam itself. The river looked wide here, at least two kilometers across. A cofferdam funneled the waters so that the work could continue, but today the river was so high and furious from the accumulation of rain from Tibet to here that no ship could safely pass. So large freighters, open-sided ferries, and gaily painted cruise ships had come to a standstill, while small fishing boats bobbed about them in the turbulent yellow waters.

The pilot landed in an open space in the far corner of a parking lot jammed with buses. Hulan glanced at Fong. “Ten minutes, okay, Pathologist?”

“I was promised a scenic tour of the Three Gorges,” he complained. “Now all I get is the visitors’ center?”

“You’ve also had a helicopter tour. How many people in Beijing can claim that?”

Everyone got out, and together they entered the visitors’ center—a large room with white lace curtains and numerous display cases. The pathologist, hoping to make the most of his ten minutes, hustled across the room to the introductory display.

The place was chockablock with baggage and cranky Chinese, Japanese, and American tourists whose boats had been unable to pass through the narrow open channel. Now they would board buses and either go downstream to Wuhan, thus ending what had been advertised as a memorable experience but had concluded as a series of sights unseen, or go to a little port farther west and head upstream against the increasingly difficult current.

Hulan gave her name to a woman in a bright kelly green uniform who sat behind the front desk. The woman called to the site and said someone would be down for the inspector in a few minutes. Hulan then found David, Fong, and the pilot staring into one of the exhibit cases. She wanted a minute alone with David, but she wouldn’t ask for it and give the pathologist more to gossip about in the MPS hallways other than that she and David hadn’t spoken during breakfast. Hulan stared at David, trying to get his attention, but he deliberately avoided her eyes.

“I guess we should get going then,” he said.

Hulan walked them to the exit. When the pilot and Fong went on ahead, she grabbed hold of David’s arm. “I think this is right,” she said, when what she meant was she wished she could relive last night, the past year, the day Chaowen first fell ill. She would do them all differently.

The hurt on his face lacerated her.

“You’ll be back tomorrow,” she said, when what she meant was that he hadn’t let her finish her confession last night. She had been ready to acknowledge fully her failure as a mother, not his as a husband and father.