Drama (23 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

Our mother lode, of course, was political satire. I had never been very vocal politically (nor have I ever been since), but the everyday politics of that era presented me with a subject too good to resist. I would arrive in the morning with a couple of willing, unpaid confederates. We would step over to the Reuters teletype in the station’s newsroom and pore over the printed pages that were rattling out of it. I would always have a couple of half-baked comedy sketches in hand, but on a good day I would jettison them in favor of up-to-the minute satirical commentary on the day’s events, fed to us by Reuters.

Our finest (or most infamous) moment came on May 2, 1972. We arrived at the station that morning and headed to the teletype. A major item of breaking news supercharged us. J. Edgar Hoover, the longtime head of the FBI, had died in his sleep. Hated and feared by every major public figure, the despicable Hoover had been miraculously transformed overnight into a beloved national hero in the public press. Reverential tributes were pouring in from statesmen of all stripes, every one of whom Hoover had terrorized with compromising information about their private lives, right up until the night before. The hypocrisy of these tributes elated us. We immediately set about providing a different perspective. We would create our own version of a J. Edgar Hoover memorial tribute, and we would put it on the radio.

As we saw it, Hoover was a creature of a bygone era. So to memorialize him we hit on the notion of parodying a 1940s “News on the March” featurette. Working at a feverish pace, we dragooned people from all over the station. We put the sound engineers to work collecting audio effects and heroic forties-era music. We hit up the news staff for arcane biographical facts. These guerrilla journalists were uncannily well-versed in all sorts of damning information about Hoover that the public was not to learn about for years—his ruthless use of blackmail, his racism, his drunkenness, his prurience, his gay companion Clyde Tolson, even his transvestitism. Armed with all of this, we wrote a five-minute script that raced from scene to lurid scene of Hoover’s shady life, mercilessly lambasting him while maintaining a gleefully ironic tone of public canonization. And the title for our venomous little screed? “J. Edgar: A Desecration of the Memory of J. Edgar Hoover.”

The WBAI staff was so thrilled with the sketch that they chose to air it at 6:25 p.m., immediately preceding their evening newscast. Seconds after it ended, the actual news came on. The lead story, of course, was Hoover’s death. It was announced in sober tones not unlike my stentorian narration of the “News on the March” parody that had gone before. The effect was like an underground nuclear blast. Until that moment I had never had a sense that anyone out in the world was actually listening to anything I produced. When you perform on the radio, you hear neither cheers nor jeers. But that night I found out just how far my voice reached. For several hours after the Hoover piece hit the airwaves, the switchboard at the station was lit up like Chinese New Year’s. We had managed to scandalize hundreds of thousands of people. A huge segment of WBAI’s listenership, the most left-wing audience in the entire nation, was appalled. To our merry band of newsroom anarchists, this was an undiluted triumph. They celebrated as if their soccer team had just won the World Cup.

The episode was the high point of my WBAI days and typified the whole crazy enterprise—raucous, reckless, politically charged, a little dangerous, and deliriously fun.

But $115 a week?!

Despite all the high times at the station, I knew that they weren’t meant to last. In terms of the hard realities of life, my low-paid radio job was barely better than unemployment. It was leading me nowhere professionally, it was never going to sustain my family, and in spite of its part-time status, it was affording me precious little time at home with my wife and baby son. At WBAI, I was just marking time until something better came along. And late that spring, just as I was reaching the end of my tether, something better

did

come along. John Stix called again.

Apparently

The Beaux’ Stratagem

had left its mark. On the strength of its success, Baltimore Center Stage had created the post of associate artistic director and was offering it to me. Although I didn’t betray the fact to Stix, I was less than ecstatic about the offer. It meant a long-term commitment to life in Baltimore and a partnership with an enigmatic man with whom I’d had an oddly strained professional relationship. Worst of all, I was being asked to give up on acting. Stix intended for me to co-manage the company with him and direct at least two productions a year. It was clear to me that he regarded my lingering acting ambitions as whimsical at best and a distraction from my intended job definition. Over the years I had taken a lot of pleasure and pride in directing. I’d had a lot of success and felt convinced of my own abilities. Associate artistic director was a title that virtually guaranteed a quick ascendancy and a blooming career. But was I ready to throw in the towel as an actor? Could I embrace a future in the theater devoid of the joy of performing? I wasn’t sure.

I had a child. My wife had supported me long enough. I was broke. I took the job.

Everyone at Center Stage was delighted. Jean was game. A press release was sent to the

Baltimore Sun

and a glowing article appeared. Packets arrived describing the pleasures of Baltimore life. Real estate agents sent apartment listings and condo brochures. Stix ran titles by me for the following season’s productions. I did my best to put an enthusiastic face on all my dealings with him and the rest of the Center Stage staff. Inside I struggled to persuade myself that, in time, the enthusiasm would be genuine.

I gave my notice at WBAI. On my last day at the station, a couple of wags from the news department asked me to record a radio sketch they’d written. It was based on a trifling news item from the night before. The sketch was a parody of the old

Mission: Impossible

TV show. It used that show’s familiar musical theme and its famous catchphrase: “Your mission, should you accept it . . .” The script featured a single voice, heard over the telephone. It was the voice of Attorney General John Mitchell. In the role of Mitchell, I instructed a silent operative to break into the offices of the Democratic National Committee in Washington, D.C. The offices were in a building called the Watergate. I didn’t know it at the time, but that morning was the dawn of the best year for satire in the history of American politics. But the sketch was the last piece of political satire I ever did. I was on my way to Baltimore.

I

never got there. A few weeks later I received yet another phone call. I recognized the cheerful voice. It belonged to a man named Arvin Brown. I sensed immediately that one of the seeds I had planted months before on one of my meandering theater junkets had finally sprouted. Arvin Brown was offering me an acting job. This time it was a job that I unequivocally wanted. Arvin was the director of New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre. Of all the theaters I’d sought out in my travels that year, Long Wharf was the one where I most wanted to work. Under Arvin’s leadership, the theater had routinely produced shows that were lavishly praised in the New York press. When I’d auditioned for him, I’d found him to be funny, sweet-natured, smart, and self-possessed. On that visit, I’d seen his brilliant production of

The Iceman Cometh

, Eugene O’Neill’s monumental portrait of New York dead-enders and alcoholics. In Arvin’s hands the play had shimmered with humor and passion, and its four hours had sped by. I sat in the audience that night and ached to climb up on the stage and join that company of marvelous actors.

And now Arvin Brown was inviting me to do just that. He was offering me a season of six roles in six terrific plays. I told him I would get right back to him. Within twenty minutes I abruptly changed the entire course of my life. I called Center Stage and, withstanding a blast of vindictive fury on the other end of the line, I withdrew from its associate artistic directorship. I called back Arvin and told him he had hired a grateful actor. In the weeks to come, Jean and I gave up our New York apartment. We relocated to Branford, Connecticut. I became a member of the Long Wharf Theatre’s resident company. I was perfectly prepared to work there for the rest of my life. But this was not to be. Long Wharf was to be my springboard to other, even more wonderful things. I began rehearsing my first Long Wharf production that September, some forty years ago, and I have barely stopped working since. I’ve often wondered about the other fork in the road, what life might have been like if I had been directing plays all this time. But I’ve never thought about it with any regrets.

What I really wanted to do was act.

Naked

W

hy do all of us want to hear stories? Why do some of us want to tell them? As long as I’ve been an actor, I’ve puzzled over those two questions. The questions are so basic, so stupidly simple, that it rarely occurs to us to even ask them. We hear about a show, we buy tickets, we file into a theater, and we sit in the darkness with a bunch of total strangers. The lights go down, the curtain goes up, and we stare at the stage, full of eagerness and hope. Why are we there? What are we looking for? What do we want? It’s a little easier to answer such questions when it comes to comedy. Everybody loves a good laugh. But what about drama? If some event in your everyday life were to make you sob uncontrollably, it would be the worst thing you ever lived through. But if something onstage made you cry that hard you would remember it as the best time you ever had in a theater. Why on earth do we subject ourselves to that? Even long for it?

Simply put, we want a good story. We want emotional exercise. We want theater to make us laugh, but we want it to make us cry too. We want to feel pity, fear, anger, hilarity, and joy, but we want these emotions delivered to us in the protective cocoon of a playhouse, and we want to experience them in a more heightened way than we ever do in our humdrum day-to-day existence. We want to be persuaded that we are intensely

feeling

beings. Why we want, need, and love such emotional exercise is a mystery. But one thing is clear: none of us can do without it.

The whole business is equally mysterious up there onstage. Hundreds of times, in mid-performance, I’ve been struck by the absurdity of my situation. All those strangers out there in the darkness are staring at me. They are all bound by some strange, unwritten contract. They must focus their eyes in reverential silence on me and my fellow actors. They must only laugh or applaud when they sense that it’s appropriate. If anyone should break this contract—if he should speak out loud, answer a cell phone, crinkle a candy wrapper, or, God forbid,

fall asleep

—he earns the stern reproof of everyone around him, while those of us onstage are peevishly indignant. And why have we agreed to this ironclad contract? It allows for a two-hour performance that the spectators all know is a completely false version of reality, but which might, just

might

provide them with a few spasmodic rushes of feeling. It is as if the actors have made an unspoken promise from the stage: You hold up your end of the bargain and we’ll hold up ours. It’s our job. We’ll make you laugh. We’ll make you cry. We’ll give you emotional exercise.

T

he Changing Room

is a play written in the early 1970s by the British playwright David Storey. Its subject is a semiprofessional rugby team in the North of England on the dark, rainy afternoon of a match. The setting is what we would call the team’s locker room but what the Brits call a changing room. Act I of the play takes place in the half hour before the match, Act II during the halftime break, and Act III immediately following the team’s victory. The cast is made up of twenty-two men. Fifteen of them are the players on the team. The rest include the coach, the trainers, the club owner, the club secretary, a referee, and an ancient janitor.

The Changing Room

is a near-documentary look at the lives of these twenty-two men during a four-hour span of their gritty lives. It is a play with virtually no plot, but as a portrait of a living, breathing, twenty-two-person social organism, it is hypnotic and moving. A year after the play’s first production in England, the Long Wharf Theatre presented its American premiere. I had just joined the Long Wharf resident acting company for a season and

The Changing Room

was our second offering. The play opened on November 7, 1972. If there was any opening night that could be said to have launched my career as a working actor, that was it.

Although he was not the production’s director, Arvin Brown had cast me somewhat arbitrarily in the role of Kendal. Kendal is a forward on the team. He is a big man with the stolidity and limited intelligence of an ox. As with every other role in the play, Kendal’s dialogue reveals almost nothing of his life outside that room. From the moment he enters, his only outward preoccupation is a newly purchased electric tool kit that he proudly shows to a couple of his teammates. Nonetheless, his character is vivid and indelible. All through Act I, Kendal is the butt of numerous jokes from his taunting teammates. The jokes sail right over his head. They obliquely hint that Kendal’s wife is a loose woman and that a few members of the team have already cuckolded him. But the earnest and unperceptive Kendal seems completely innocent of this knowledge. Reading the play, I instantly fell in love with the part.

In the play’s middle act, halfway through the match, the team bursts back into the changing room like a herd of panting cattle. They are covered with mud, numb with cold, and gasping for breath. They are losing the match, and this makes them foul-tempered and quarrelsome. They guzzle water bottles, nurse cuts and bruises, and endure the hectoring pep talk of their coach. Then they pull themselves together and roar back out for the second half of play. A little time passes with only the janitor left on the empty set, listening to occasional muffled phrases from the game’s announcer over a crackly speaker in a corner of the room.

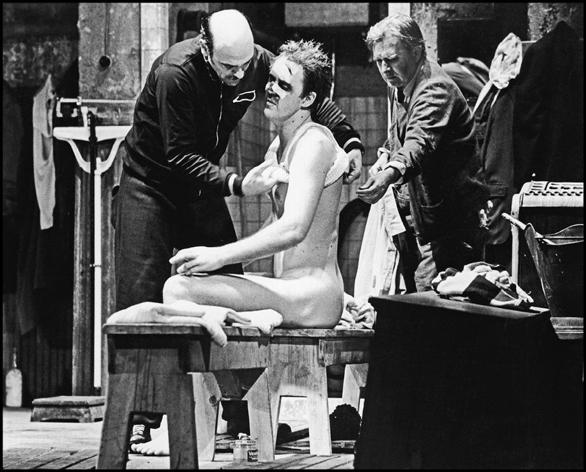

Photograph by William L. Smith. Courtesy Long Wharf Theatre.

Suddenly one of the players is brought back in, having just been seriously injured on the field. He bays with pain. His nose is broken and streams with blood. His eyes are so swollen he can barely see. He struggles so violently that his coach and two trainers must pin him to the training table. They tend to him with ointments and cotton swabs. One of the trainers helps him into an adjoining room, where he bathes himself in a big communal tub, unseen by the audience. After a couple of minutes, the trainer helps the injured player back onstage. He is naked, disoriented, and glistening with bathwater. The trainer sits him down on a bench and ministers to him. In a long, virtually wordless scene, with only the distant roar of the crowd filling the air, the trainer towels the player down from head to foot, dresses him like a helpless child, bundles him up, and steers him toward the door, returning him to the desolation of his bleak life. Just before he reaches the door, the injured player remembers, through the fog of his addled mind, something he has left behind in the changing room. It is his electric tool kit.

The injured player is Kendal. My part.

And by a happy chance, so typical of the serendipity of our profession, the trainer was to be played by my good friend, the former McCarter Theatre “Don Pedro,” John Braden.

We’d been given four weeks of rehearsal. Our director was Michael Rudman, a sardonic Texan who had long since emigrated to England. By yet another stroke of serendipity, Michael had been the man who hired me to coach American accents at the RSC in London, three years before. Under his deft direction, our sprawling production took shape. He tapped into the testosterone coursing through the veins of a twenty-two-man ensemble. He sent us off to a park to play touch football together. He brought in a Yale coach to dispense the basic rules of rugby. He steeped us in the guttural molasses of North Country accents. He showed us David Storey’s rugby film

This Sporting Life

. He noted the competitiveness, showmanship, insecurity, and physical jeopardy in the lives of both actors and athletes. Cannily drawing parallels between the two professions, Michael unleashed us, forging a show that surged with masculine energy.

Nudity, of course, was an essential element of the staging. Professional athletes don’t enter and exit a locker room on the day of a game without twice taking off all of their clothes. But Michael was intent that nudity should not be the play’s titillating main event. He wanted it to emerge as part of the overall texture of the production, so frank and realistic as to pass virtually unnoticed. As he saw it, this openness needed to characterize even the rehearsal process. Notwithstanding the presence of Annie Keefe, our attractive young stage manager, all traces of hesitancy or self-consciousness had to be banished. In this, Michael had an eager confederate in the horse-faced Rex Robbins. Rex was a veteran character man with a dry, winning manner and a readiness to try anything onstage. He played the part of Fielding, the oldest player on the team. On our second day of work he casually shed every stitch of clothing, striding around the rehearsal room as if it were the most natural thing in the world and startling everyone with the size of his softball-shaped scrotum. Rex’s insouciance had the desired effect. In no time at all, the rugby players in the cast went from giggly and self-conscious to offhand and swaggering. Some moved right on to flat-out exhibitionistic. Weeks later, at our drunken opening-night party, most of the company strutted around with a newfound, cocksure manliness. The rest giddily sprinted out of the closet. One or two did both.

Similarly, the larger concept of onstage nudity evolved in our minds over the course of the rehearsal period. Initially the subject of embarrassed laughter, we began to see nudity as the most potent theatrical expression of vulnerability and naked truth. Serious acting is a constant effort to illuminate, expose, and unlock emotion. There is no escaping its essential pretense, but actors are always striving to make that pretense invisible, to present life with such honesty that members of the audience momentarily forget that they are watching a play. And what is more honest than a naked body? Of course the use of nudity onstage needs to be handled with great care. A naked person standing in front of hundreds of other people is such an unfamiliar, unsettling event that it is just as likely to make an audience recoil as to disarm them. But supported by a superb play and a deft, deeply felt production, we had the growing sense that, with

The Changing Room

, we were about to work a minor theatrical miracle.

In the days leading up to our first performance, Michael presided over the obligatory technical and dress rehearsals. For long, tedious hours, the cast shuffled through the staging while he carefully adjusted all the tech aspects of the production around us. He calibrated the sounds of the crowd that emanated from the offstage rugby pitch, the rain that streaked the grimy windowpanes, the harsh glare of the overhead lamps, and the slate-gray daylight outside the windows as it gradually faded to darkness. Every visual and aural detail was calculated to create the superrealistic illusion of that room on that day in that part of northern England. Even odors came into play: all through Act I, as we prepared for the match, we rubbed wintergreen onto our bare thighs so that its astringent smell would fill the theater for every performance.

One naturalistic detail was utterly unique, especially to American audiences. This was the large offstage bathtub. Communal bathing after an athletic event was unheard of in the U.S. (and has since disappeared in the U.K. as well). But it was

de rigueur

in the time and place of

The Changing Room

. Although Michael placed the tub out of the sight of the audience, he made it a vivid part of the action of the play. As with every other aspect of his production, he didn’t want the unseen bathtub activity to betray a hint of artifice. In Act III he wanted the audience to hear the players sloshing around and braying their bawdy songs as they bathed together. He wanted cascades of bathwater to splash into the open doorway and onto the duckboards on the changing room floor. When the players entered from the bath, he wanted their pale bodies dripping wet and flushed pink from the hot water. And of course there was that key scene in Act II: Kendal exits the stage covered in mud and blood, plunges into the offstage tub, and reemerges a few minutes later, washed clean.

In the rehearsal room, we had merely gone through the motions of bathing. At the first tech rehearsal, the crew filled up the tub and we bathed in earnest. The effect was sensational. None of us had ever felt so goddamned

real

onstage. But after the first few hours, reality struck back. The tub sprung a leak. The crew drained it immediately, let it dry out, coated the seams with thick layers of caulking, then let it dry out again. The whole process took a couple of days. In the meantime, we pressed on with our tech rehearsals, minus the water and the mud, pretending to bathe just as we had in the rehearsal room.