Drink (13 page)

Authors: Iain Gately

Their discoveries benefited secular vintners, who made the best out of the remaining patches of land in the region, so that by 1285 when Fra Salimbene, an Italian cleric, visited Burgundy, he was astonished to discover that it had become a monoculture: “The people of the region do not sow or reap or gather into barns, but they send their wine to Paris . . . [via river]. . . . They sell it at a good price and from this they get all their food and clothing.” He also waxed lyrical over the quality of the wines they produced: “They give off a delicate aroma, they are very comforting and very delicious; they give all who drink them peacefulness and cheerfulness.”

The Cistercian rule possessed a breeder clause: As soon as any monastery had more than sixty monks, twelve of them had to leave to found a new one. There were four hundred Cistercian monasteries when St. Bernard died in AD 1153, and two thousand a century later. The breeder clause spread the Cistercians and their mania for winemaking far and wide. From France they moved on to Germany, where they founded the monastery of Eberbach on the banks of the Rhine. Within a hundred years Eberbach had itself spawned more than two hundred children and had become “the largest vine-growing establishment in the world.” The Cistercians even had a go in England. Their abbey in Beaulieu, near Southampton, was planted out with vines, although the fluid these produced seems to have been atypically bad. When King John tried it in 1204 he instructed his steward to “send ships forthwith to fetch some good French wine forthwith for the abbot.”

In those parts of Europe where it was hard to grow vines, or where the native drink was ale, the religious orders applied themselves to brewing. As had been the case with wine, they focused on quality, and the results were equally good. A number of twenty-first-century breweries and brews owe their origin to medieval monasteries, including Weihenstephan, founded in AD 1040, and Leffe (AD 1240). Religious enthusiasm toward brewing resulted in part from the understanding that ale, having the same ingredients as bread, could be drunk without sin when on a diet of bread and water, and that therefore the fasts that littered their calendar need not be too unpleasant. They were, however, limited to an allowance of eight pints per day. Nunneries had breweries, too, and it was a nun, the Blessed Hildegard von Bingen (d. 1179), abbess, brewster, botanist, and mystic, who first noted that hops had preservative qualities when added to ale. They also imparted a bitter flavor, which many found agreeable, and the practice of hopping ale spread from religious breweries to secular ones.

The steady drinking of the clergy was light in comparison to the constant guzzling of the nobility, who, together with their households, got through quantities of alcohol that would have stunned even the degenerate wine lovers of Pompeii. Those at the pinnacle of feudal society proclaimed their status through excess. They dressed magnificently and forbade the practice of doing so in the same style to the clergy and the commoners. They built ostentatious palaces, where they feasted their fighting men and other retainers and, if they could afford them, exotica such as jesters and midgets; and they drank like lords. Such extravagance was not merely hedonism but a duty. It was part and parcel of being upper class. The responsibility is apparent in an English allegorical poem of the period entitled “Winner and Waster,” which represents acts of conspicuous distribution and consumption as being the perfect expressions of the aristocratic ethos.

In England, where wine was imported, expensive, and therefore noble, the demand of its gentry sparked a viticultural revolution in the Bordeaux region of France. This had become English soil following the marriage of Henry Plantagenet to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152, and both events proved to be love matches. In the case of Bordeaux wines, the desire of the English aristocracy to buy was equaled by the willingness of the Bordelaise to plant, harvest, ferment, and sell. The relationship was encouraged by the king of both places, who abolished some of the taxes on the wine trade, and by the first quarter of the thirteenth century, Bordeaux was exporting about twenty thousand tons of wine per year to England. Its target market was comprised of the English feudal lords, whose monarch, as principal aristocrat, led by example. In 1307, for instance, King Edward II ordered a thousand tons of claret for his wedding celebrations—the equivalent of 1,152,000 bottles. To place the number in its proper perspective, the population of London, where the celebrations took place, was less than eighty thousand at the time.

The volume of consumption, even by modern standards, was remarkable: Fourteenth-century levels of wine exports from Bordeaux to England were neither matched nor exceeded until the 1920s. However, the beverage at the heart of the trade was no Falernian. The classical concept that wine, if properly stored, could improve with age had been forgotten during the Dark Ages. Wine was fermented and transported in wooden barrels, instead of being sealed inside amphorae, and as a consequence Bordeaux’s vintages were usually vinegar before they reached their second birthday. The oenophiles of the Middle Ages prized new wine over old, and this preference was reflected in the mechanics of the Bordeaux wine trade. Because of the instability of its product, the wine fleet delivered two shipments each year. The first, in late autumn, carried new wine, the second, in winter, brought

reek

wine, an inferior product fermented from the lees of the first pressing. When the new wine arrived in England there was panic selling of anything left over from last year’s vintage, and panic buying of the new. All this for a thin, pink, fizzy fluid, with the generic name of

claret,

which might turn acidic at any moment.

reek

wine, an inferior product fermented from the lees of the first pressing. When the new wine arrived in England there was panic selling of anything left over from last year’s vintage, and panic buying of the new. All this for a thin, pink, fizzy fluid, with the generic name of

claret,

which might turn acidic at any moment.

Few commoners, the third category of human beings in feudal England, ever tasted claret. Their staple was ale, which, to them, was rather food than drink. Men, women, and children had ale for breakfast, with their afternoon meal, and before they went to bed at night. To judge by the accounts of the great houses and religious institutions to which they were bound by feudal ties, they drank a great deal of it—a gallon per head per day was the standard ration.

8

They consumed such prodigious quantities not only for the calories, but also because ale was the only safe or commonly available drink. Water was out of the question: It had an evil and wholly justified reputation, in the crowded and unsanitary conditions that prevailed, of being a carrier of diseases; milk was used to make butter or cheese and its whey fed to that year’s calves; and cider, mead, and wine were either too rare or too expensive for the average commoner to use to feed themselves or to slake their thirsts.

8

They consumed such prodigious quantities not only for the calories, but also because ale was the only safe or commonly available drink. Water was out of the question: It had an evil and wholly justified reputation, in the crowded and unsanitary conditions that prevailed, of being a carrier of diseases; milk was used to make butter or cheese and its whey fed to that year’s calves; and cider, mead, and wine were either too rare or too expensive for the average commoner to use to feed themselves or to slake their thirsts.

Ale was so vital to the very existence of the third estate that its price and quality were regulated by law. In 1267, King Henry III issued a pioneering piece of consumer protection legislation—the Assize of Bread and Ale—which set the maximum retail price of town-brewed ale at one penny for two gallons; the same penny bought three gallons from a country brewer. Prices were to be reviewed each year and could be adjusted in accordance with fluctuations in the cost of grain. The assize also provided for the appointment of ale tasters, who were responsible for quality control. The ale tasters recognized two grades of ale—“good,” or “clear,” ale, and plain ale. The better sort could be sold at a premium, the plain variety had to pass certain minimum standards. Anyone producing inadequate ale could be punished with fines, time in the stocks, or a ducking in the nearest pond or river.

The immense demand for ale was satisfied by many thousands of brewers, or rather brewsters, for the majority of them were female. Brewing was one of the few trades open to medieval women. It was generally practiced as a cottage industry—whenever a brewster brewed, there was usually a small surplus for sale, so a family might drink ale of their own manufacture one week, sell the excess to their neighbors, then buy their neighbor’s ale the following week. The typical brewster sold less than a hundred gallons of ale each year. She brewed using buckets, jugs, and troughs—whatever she had on hand. A rare few ran substantial breweries, owned plant, employed servants, and enjoyed otherwise male privileges such as the ability to sign contracts on their own behalf.

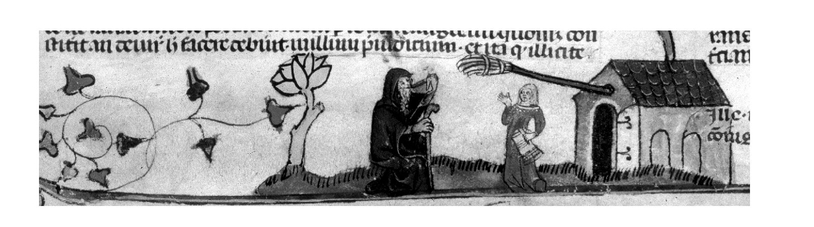

Hermit and ale house

Most home-brewed ale was sold locally and quickly. It had a shelf life of a week at best, and it spoiled if it was agitated in travel. This perishability accounts, in part, for the number of brewsters; indeed it has been estimated that “almost every other household [in England] brewed for profit in the countryside, and about one household in every fifteen brewed for commercial purposes in towns.” The ale trade between commoners was divided into on- and off-premises sales. Peasants either brought their own containers to a brewster’s door for her to fill; or a room, or area, in her household would be set aside and drinking vessels supplied for people to consume the ale they purchased in situ. Places offering on-sales were designated

alehouses

and were regulated by law. They were required to declare their presence, and that they had ale for sale, by hanging a bush from a pole outside their front doors. This was a signal and invitation to the local ale taster to come and verify the quality of the ale and set the price at which it might be sold. Ale had to be offered in fixed measures—the assize of 1277 declared, “No brewster henceforth shall sell except by true measures, viz., the gallon, the pottle,

9

and the quart.”

alehouses

and were regulated by law. They were required to declare their presence, and that they had ale for sale, by hanging a bush from a pole outside their front doors. This was a signal and invitation to the local ale taster to come and verify the quality of the ale and set the price at which it might be sold. Ale had to be offered in fixed measures—the assize of 1277 declared, “No brewster henceforth shall sell except by true measures, viz., the gallon, the pottle,

9

and the quart.”

Despite their impressive average intake of ale, English commoners were not considered to be perpetual drunkards by their rulers or their priests. This title was reserved for a subcategory of the feudal system—students. These privileged creatures were a by-product of the fundamental transformation of higher learning that had occurred in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. Hitherto, education had been the province of monasteries, and had focused on the solution of such knotty metaphysical problems as how the Holy Ghost had impregnated the Virgin Mary. However, as the bureaucracies of both church and state evolved, a need arose for numerate, literate clerks to administer them, and universities sprang up across Europe—in Paris, Salerno, Oxford, Padua, and Toledo. In some of these places, their scholars formed a significant part of the population: At the end of the twelfth century, ten percent of the inhabitants of Paris were students.

Students enjoyed all the same privileges as the clergy. They could not be prosecuted in the secular courts, which effectively placed them above the law in the towns where they studied, and they were notorious for abusing their rights and running riot. When matters got out of hand, the nobility and clergy stepped in on their side. In Paris, for instance, after a series of riots over the price of wine in taverns had led to the death of both townspeople and scholars, the students were pledged the special protection of the pope, the king of France, and the Holy Roman Emperor. As a consequence of such favoritism, they were hated by the townspeople. They also infuriated pious clerics by the levity with which they treated Mother Church. Parisian students were notorious for their blasphemous frivolity. A preacher of that age observed that they respected neither the rituals of their faith nor the places in which it was practiced. He was particularly irked by the

herring game,

which students played during high mass every Sunday: A group of them would enter the church in single file, each trailing a raw herring on a string from the hem of his gown. The aim of the game was to tread on the herring of the person in front, while preventing anyone from stepping on your own. Fresh herrings were required for each new round.

herring game,

which students played during high mass every Sunday: A group of them would enter the church in single file, each trailing a raw herring on a string from the hem of his gown. The aim of the game was to tread on the herring of the person in front, while preventing anyone from stepping on your own. Fresh herrings were required for each new round.

The students, both by their own admission, and to the disgust of their critics, were fanatical drinkers. They employed their learning to compose Latin songs and poems in praise of their favorite pastime, some of which have survived in a German manuscript written circa 1230, known as the

Carmina Burana

. The

Carmina Burana

is tantamount to a medieval student manifesto. Its contents reflect its authors’ preoccupations—wine, love, nature and adventure, and a contempt for institutional authority. The students referred to themselves within the manuscript as the

goliards

(probably a corruption of the Latin word for “glutton”). The most famous of their number, known as “the Archpoet,” summed up their philosophy in his masterpiece “The Confessions of Golias”:

Carmina Burana

. The

Carmina Burana

is tantamount to a medieval student manifesto. Its contents reflect its authors’ preoccupations—wine, love, nature and adventure, and a contempt for institutional authority. The students referred to themselves within the manuscript as the

goliards

(probably a corruption of the Latin word for “glutton”). The most famous of their number, known as “the Archpoet,” summed up their philosophy in his masterpiece “The Confessions of Golias”:

In the public house to die

Is my resolution

Let wine to my lips be nigh

At life’s dissolution

That will make the angels cry

With glad elocution:

Grant this drinker, God on high,

Grace and absolution

Is my resolution

Let wine to my lips be nigh

At life’s dissolution

That will make the angels cry

With glad elocution:

Grant this drinker, God on high,

Grace and absolution

The goliards were satirists in addition to being poets. They produced several parodies of divine service, called Missae de Potatoribus— Masses for Drinkers. These were Christian in their form but bacchanalian in spirit, as is apparent in their version of the Paternoster:

PRIEST: Our Father, who art in glasses, hallowed be thy wine. May the cups of Bacchus come, may thy storm be done in wine as it is in the tavern, give us this day our bread for the devouring, and forgive us our great cups, as we forgive not drinking, and lead us not into the absence of wine, but deliver us from our clothing.

CONGREGATION: Amen.

Other books

Little Better than a Beast (Marla Mason) by Pratt, T.A.

The Mere Future by Sarah Schulman

In the Land of Armadillos by Helen Maryles Shankman

On Earth as It Is in Heaven by Davide Enia

The Painted Cage by Meira Chand

The Longest Winter by Mary Jane Staples

The Recluse Storyteller by Mark W Sasse

Baller's Baby - A Bad Boy Romance by Bliss, Saylor

Running Blind / The Freedom Trap by Desmond Bagley