Drink (21 page)

Authors: Iain Gately

The problem was exacerbated by the relative abundance of spirits, versus other drinks, in the Americas. Their concentrated form made them easier to carry across the Atlantic than wine or beer, so that unlike most Europeans, who started drinking beer or watered wine while children, the first contact a Native American had with alcohol was likely to be with strong waters, a mouthful or two of which was enough to produce an altered state of consciousness. Thereafter, they would look to drink for stimulation rather than mere refreshment, and since their cultures did not possess rituals and safeguards as to when and how much to drink, many very quickly ruined themselves on the white man’s wicked water.

11 RESTORATION

The thirsty earth soaks up the rain,

And drinks and gapes for drink again;

The plants suck in the earth, and are

With constant drinking fresh and fair;

The sea itself (which one would think

Should have but little need of drink)

Drinks twice ten thousand rivers up,

So fill’d that they o’erflow the cup.

The busy Sun (and one would guess

By ’s drunken fiery face no less)

Drinks up the sea, and when he’s done,

The Moon and Stars drink up the Sun:

They drink and dance by their own light,

They drink and revel all the night:

Nothing in Nature’s sober found,

But an eternal health goes round.

Fill up the bowl, then, fill it high,

Fill all the glasses there—for why

Should every creature drink but I?

Why, man of morals, tell me why?

And drinks and gapes for drink again;

The plants suck in the earth, and are

With constant drinking fresh and fair;

The sea itself (which one would think

Should have but little need of drink)

Drinks twice ten thousand rivers up,

So fill’d that they o’erflow the cup.

The busy Sun (and one would guess

By ’s drunken fiery face no less)

Drinks up the sea, and when he’s done,

The Moon and Stars drink up the Sun:

They drink and dance by their own light,

They drink and revel all the night:

Nothing in Nature’s sober found,

But an eternal health goes round.

Fill up the bowl, then, fill it high,

Fill all the glasses there—for why

Should every creature drink but I?

Why, man of morals, tell me why?

—“Drinking,” Abraham Cowley

A significant proportion of the strong waters arriving in the Americas were there courtesy of the Dutch, who, by the middle of the seventeenth century, were the largest maritime trading nation in the world. Their rise to eminence had, in historical terms, been exceptionally rapid: Prior to 1566, their nation was a patchwork of duchies and bishoprics under the control of Spain. However, over the following decades, seventeen of these entities, mostly Protestant, combined together to form the

United Provinces,

and with the assistance of England they established a republic and drove the Spaniards from their lands. Overseas, meanwhile, they appropriated a number of Portuguese colonies and founded, as in America, new stations of their own. By 1648, when the Peace of Westphalia, a pan-European settlement of various conflicts, was agreed and their nation recognized, they had trading posts in Manhattan, the Caribbean, Africa, India, Sri Lanka, and various Indonesian Islands. They carried Virginian tobacco to Europe, African slaves to the Americas, French wine and brandy everywhere, and they had a near monopoly on Asian spices.

United Provinces,

and with the assistance of England they established a republic and drove the Spaniards from their lands. Overseas, meanwhile, they appropriated a number of Portuguese colonies and founded, as in America, new stations of their own. By 1648, when the Peace of Westphalia, a pan-European settlement of various conflicts, was agreed and their nation recognized, they had trading posts in Manhattan, the Caribbean, Africa, India, Sri Lanka, and various Indonesian Islands. They carried Virginian tobacco to Europe, African slaves to the Americas, French wine and brandy everywhere, and they had a near monopoly on Asian spices.

Their modus operandi, backed up by force if necessary, was similar wherever they traded. The breadth of their commercial network allowed them to match supply and demand however distant, and they encouraged suppliers to grow specific products and process them in a particular manner. They provided technical assistance to ensure the suppliers got it right, paid cash for their produce, and offered easy terms for those goods the suppliers themselves most valued and which they carried to them. The Dutch method was honed in the Bordeaux region of France, where they had long been buyers of its wines. In order to stimulate supply, they sent in engineers to reclaim land and build dykes (a Dutch specialty) and provided vines and loans and barrels and a guaranteed market to any vintners willing to work with them. In return, they wanted cheap sweet white wine, and plenty of it.

Their system created losers as well as winners. Traditional growers in Bordeaux exported via its port, which still levied medieval duties on ships bringing wine down the river Gironde. These were, in Dutch eyes, unnecessary costs. They therefore dropped their customary suppliers and transferred their attentions inland toward the Dordogne, and north, to the hinterland behind La Rochelle. Here they offered their standard incentives to growers and shipped their purchases around the tariff walls. The Dutch wanted their wine to be stable as well as inexpensive. To this end they introduced the technology of fumigating wine barrels with sulphur matches, and the practice of fortifying the wine itself with ardent spirits. These two measures extended its lifespan, and the taste of sulphur wore off as it aged.

In some economic-captive areas of France, the Dutch elected to export brandy instead of wine fortified with the same. The region they focused on was the Charente, in particular the district around the village of Cognac, which was perfectly situated for the manufacture of spirits. Its principal advantages were, in order of importance, the proximity of a duty-free port, the abundance of firewood (necessary to heat stills), and plenty of substandard wine. In the event, thanks to chalk in the soil, the wine of the region proved to be peculiarly well suited to distillation, and the finished item—c

ognac

—acquired a reputation as a superior beverage. It had fans in England by 1594, Native American victims two decades later, and was used subsequently to prize open new markets elsewhere. In 1652, the Dutch purchased a substantial block of land in the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa for a few barrels of Cognac and some good Virginian tobacco. Cape Town became a vital staging post for their Asian trading fleet, and to save transport costs, they imported breeding livestock and planted their new colony with all the standard provision crops, including vines, perhaps the first to be cultivated in sub-Saharan Africa.

ognac

—acquired a reputation as a superior beverage. It had fans in England by 1594, Native American victims two decades later, and was used subsequently to prize open new markets elsewhere. In 1652, the Dutch purchased a substantial block of land in the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa for a few barrels of Cognac and some good Virginian tobacco. Cape Town became a vital staging post for their Asian trading fleet, and to save transport costs, they imported breeding livestock and planted their new colony with all the standard provision crops, including vines, perhaps the first to be cultivated in sub-Saharan Africa.

Go-betweens to most of the world, the Dutch kept the pick of the cornucopia of goods that they traded for themselves. The decades during which they flourished and won their independence were characterized by suffering in much of the rest of Europe. Wars religious, civil, and despotic rolled back and forth across the continent, so that by the time that Peter Stuyvesant was planting his cider apple orchard in Manhattan, his native land was “an island of wealth surrounded by a sea of want.” The Dutch were conspicuous consumers on home soil, in both public and private life. They staged elaborate functions for their various civic bodies and militia, including feasts that lasted several days, at which mountains of delicacies were served out on gold and silver plate. These events took place in purpose-built halls whose walls were covered with tapestries and oil paintings, where their participants enacted rituals centered around the sharing of food and drink. Such rituals, all of which had been invented within the lifespan of the republic, and most of which involved communal intoxication, helped it to establish an identity. Heavy drinking was part of being Dutch. Despite the relative youth of these ceremonies, they were surprisingly sophisticated and amazed foreigners with their complexity. After attending one such formal binge, a French visitor commented, “All these gentlemen of the Netherlands have so many rules and ceremonies for getting drunk, that I am repelled as much by them as by the sheer excess.” The sheer excess was striking. An English observer at a Dutch

schutter

party in 1634 reported, “I do not believe scarce a sober man was to be found among them, nor was it safe for a sober man to trust himself among them, they did shout so and sing, roar, skip, and leap.”

schutter

party in 1634 reported, “I do not believe scarce a sober man was to be found among them, nor was it safe for a sober man to trust himself among them, they did shout so and sing, roar, skip, and leap.”

Drunkenness was ubiquitous in the young republic. Its towns were packed with taverns, and the Dutch demonstrated their disdain for the medieval notion that these might lead them into sin by giving them provocative names, such as the

Beelzebub

in Dortrecht, and the

Duivel aan de Ketting

(Devil on a Chain) in Amsterdam. Drink and be damned was their ethos. The Dutch imbibed for nourishment as well as intoxication, and the alcoholic part of their diet reflected the wealth of choice they enjoyed in comparison to commoners elsewhere. Workingmen breakfasted not merely on beer but on such luxurious beverages as

Wip,

which was comprised of warm ale, nutmeg, sugar, egg whites, and brandy. They topped themselves up throughout the working day with various brews, with wine, and a shot or two of spirits. They drank with every meal, they sealed bargains over a drink— there was no occasion in which alcohol was inappropriate. Indeed, the Calvinist pastor Peter Wittewrongel, as part of a general philippic against sin, complained in 1655 that “men drink at the slightest excuse . . . at the sound of a bell, or the turning of a mill.”

Beelzebub

in Dortrecht, and the

Duivel aan de Ketting

(Devil on a Chain) in Amsterdam. Drink and be damned was their ethos. The Dutch imbibed for nourishment as well as intoxication, and the alcoholic part of their diet reflected the wealth of choice they enjoyed in comparison to commoners elsewhere. Workingmen breakfasted not merely on beer but on such luxurious beverages as

Wip,

which was comprised of warm ale, nutmeg, sugar, egg whites, and brandy. They topped themselves up throughout the working day with various brews, with wine, and a shot or two of spirits. They drank with every meal, they sealed bargains over a drink— there was no occasion in which alcohol was inappropriate. Indeed, the Calvinist pastor Peter Wittewrongel, as part of a general philippic against sin, complained in 1655 that “men drink at the slightest excuse . . . at the sound of a bell, or the turning of a mill.”

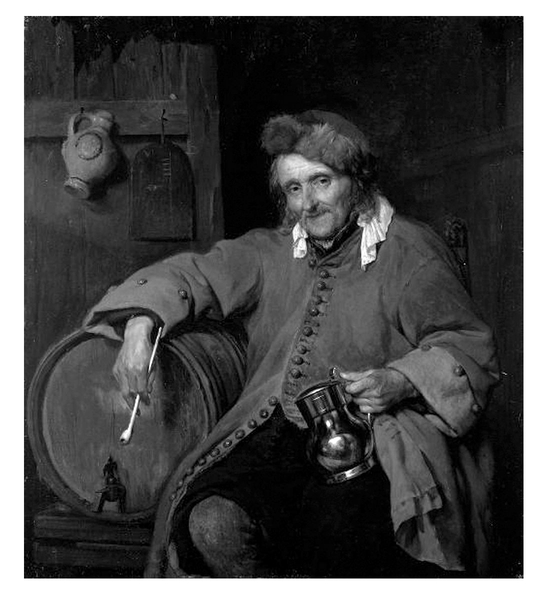

The Dutch celebrated their good fortune in their visual art. They commissioned tavern scenes from painters, showing ordinary people socializing, drinking, and smoking. This was an innovation. Hitherto, no one had wasted paint on peasants, unless as incidental figures in the background, present as an aid to perspective, or to direct the eye with their praise and diminished stature toward a saint or a noble. Moreover, these revolutionary canvases, depicting ordinary people in everyday clothes and unselfconscious postures, were affectionate without being sentimental in their treatment of their subjects. The spirit of the new genre is apparent, reduced to a single figure, in Gabriel Metsu’s canvas of a Dutch drinker (c. 1660). This depicts an old soldier seated on a bench with one arm slung over a beer barrel, as if it were a lover or his best friend. He holds a long clay pipe in the fingers of his left hand, like an artist with a paintbrush. In his right hand is a shining pewter tankard. His expression is alert and mischievous. The beer barrel has a faded stencil of a red stag on its face. Technically, the painting is on a par with Italian Renaissance standards; philosophically, it is an aeon apart.

Gabriel Metsu’s

The Old Drinker

The Old Drinker

The luxury and plenty enjoyed by the Dutch in the middle third of the seventeenth century stands in stark contrast to the poverty and strife that the English endured over the same period. Two civil wars were fought between 1642 and 1649, which culminated in the execution of King Charles I and the declaration of a commonwealth by the remnants of Parliament. From 1653 to 1658, the country was a protectorate under the puritan Oliver Cromwell, during which period the theaters were closed, press censorship was imposed, and an

excise,

i.e., consumption, tax on beer and ale was introduced.

excise,

i.e., consumption, tax on beer and ale was introduced.

These austere times came to an end with the restoration of King Charles II in 1660. Known as the “Merrie Monarch,” Charles had spent much of the preceding decade in exile at the French court, where his natural hedonism had flowered. Upon his return to England he reopened the theaters, encouraged the arts and sciences, and set an example as a libertine that his court strove to emulate. A spirit of decadence flourished, which included a passion for fine wines, and plenty of them. Daniel Defoe, passing comment on the initial years of the Restoration half a century later, noted that “our drunkenness as a national vice takes its epoch at the Restoration. . . . Very merry, and very mad, and very drunken the people were, and grew more and more so every day.”

The Restoration ethos was embodied in the courtier and poet John Wilmot, first Earl of Rochester. His portrait shows a young man with a slim face, Mae West lips, and long fluffy chestnut hair, but does not do credit to his actual debauchery. His lyrical, often pornographic verse, much of which was topical, delighted English society. His life was short and alcoholic—“in a course of drunken gaiety and gross sensuality, with intervals of study perhaps yet more criminal, with an avowed contempt of all decency and order, a total disregard to every moral, and a resolute denial of every religious obligation . . . [Rochester] lived worthless and useless, and blazed out his youth and his health in lavish voluptuousness.” Before, however, he died from syphilis aged thirty-three, Rochester made some graceful contributions to the drinking canon. He considered wine to be “Poetick Juice” and acknowledged its influence, together with sex, over his work:

Cupid and Bacchus my saints are;

May drink and love still reign:

With wine I wash away my cares,

And then to cunt again.

May drink and love still reign:

With wine I wash away my cares,

And then to cunt again.

Wit, wine, and love were the Holy Trinity of Restoration lyrical poets. Their output was encouraged by gifts from the court and patronage by its nobles.

17

Similar themes prevailed in Restoration theater, whose principal genre was comedy. New plays were topical, with convoluted plots, rakish aristocratic characters, and plenty of tippling. Their contemporary settings provide a guide to prevailing drinking habits and highlight the fashion for wine, especially French wine. While sack was considered appropriate for poets, the court and nobil-ityhad moved on to

Haut-Brion

and

champagne

. The former was a red wine from Bordeaux, whose producers had discovered the concept of quality and the power of marketing. Haut-Brion was the antithesis of the pink rotgut the English had bought in spectacular quantities in the Middle Ages. Its appearance in England, and its memorable flavor, were recorded by Samuel Pepys, in his diary entry for April 10, 1663: “Drank . . . a sort of French wine, called Ho Bryan, that had a good and most particular taste that I ever met with.” Haut-Brion was a deep ruby in color and, if properly kept, had a lifespan of several years. It was shipped to England in casks, where it was sold at exorbitant prices in taverns or carted off to stately homes and bottled.

17

Similar themes prevailed in Restoration theater, whose principal genre was comedy. New plays were topical, with convoluted plots, rakish aristocratic characters, and plenty of tippling. Their contemporary settings provide a guide to prevailing drinking habits and highlight the fashion for wine, especially French wine. While sack was considered appropriate for poets, the court and nobil-ityhad moved on to

Haut-Brion

and

champagne

. The former was a red wine from Bordeaux, whose producers had discovered the concept of quality and the power of marketing. Haut-Brion was the antithesis of the pink rotgut the English had bought in spectacular quantities in the Middle Ages. Its appearance in England, and its memorable flavor, were recorded by Samuel Pepys, in his diary entry for April 10, 1663: “Drank . . . a sort of French wine, called Ho Bryan, that had a good and most particular taste that I ever met with.” Haut-Brion was a deep ruby in color and, if properly kept, had a lifespan of several years. It was shipped to England in casks, where it was sold at exorbitant prices in taverns or carted off to stately homes and bottled.

Other books

Beyond Infinity by Gregory Benford

Moon Flower by James P. Hogan

Hidden Steel by Doranna Durgin

Some Like It Hot by Zoey Dean

Starfall by Michael Cadnum

Death's Awakening by Cannon, Sarra

Warlord by Crane, Robert J.

The Pirate's Daughter by Robert Girardi

The Ghost Who Loved Me by Karolyn Cairns

Broken Heart 07 Cross Your Heart by Michele Bardsley