Drink (41 page)

Authors: Iain Gately

Poe knew his business when writing about inebriates. He was as famous, in his lifetime, for his drinking as his composition. Not even his opium addiction could save him from a drunkard’s death, around which there remains a mystery similar to those in his best stories. Like the Washingtonian Gough, he vanished for five days, at the end of which period he was found drunk, disheveled, and sick. He died before he sobered up. A theoretical solution to the mystery has Poe captured by the agents of a political party, forced to drink whiskey, then compelled to make multiple votes for their candidate, day after day, until he collapsed, but this was only the most probable of many conjectures.

During the forty years that Poe had lived, American temperance had evolved from a marginal activity practiced by a handful of eccentrics to a mainstream political cause. In addition to indulging in biblical revisionism, and introducing monstrous dipsomaniacs

39

to American fiction, the country’s temperance organizations had taken advantage of the federal nature of the United States to propose legislation against drink at the state level. Early victories made them bold. In 1838 they pressured Maine into passing a

Fifteen-Gallon Law,

so-called because it prohibited the sale of ardent spirits in any lesser quantity. This tactic—which aimed to squeeze out small retailers and casual tipplers by putting strong drink beyond the reach of their purses—had been tried before in England at the height of the gin craze and had failed. In the event, the Fifteen-Gallon Law also failed and was repealed within two years as being antidemocratic. The rich drank wine, which was unaffected by the law, and could, if they so desired, scrape together the four dollars or so required to buy fifteen gallons of whiskey. The poor, in contrast, were denied access to their favorite solace.

39

to American fiction, the country’s temperance organizations had taken advantage of the federal nature of the United States to propose legislation against drink at the state level. Early victories made them bold. In 1838 they pressured Maine into passing a

Fifteen-Gallon Law,

so-called because it prohibited the sale of ardent spirits in any lesser quantity. This tactic—which aimed to squeeze out small retailers and casual tipplers by putting strong drink beyond the reach of their purses—had been tried before in England at the height of the gin craze and had failed. In the event, the Fifteen-Gallon Law also failed and was repealed within two years as being antidemocratic. The rich drank wine, which was unaffected by the law, and could, if they so desired, scrape together the four dollars or so required to buy fifteen gallons of whiskey. The poor, in contrast, were denied access to their favorite solace.

This setback did not deter the abolitionists nor harm their cause. New temperance societies sprang up like weeds. The Sons of Temperance were joined by the Independent Order of Rechabites, the Sons of Jonadab,

40

the Daughters of Temperance, the Templars of Honor and Temperance, the Colored Temperance Society, and a host of other local, regional, and national organizations dedicated to ridding the United States of alcohol. The ubiquity of the movement was a matter for satirical comment among the majority of Americans who still drank, to whom it seemed that the country was being overrun by the T-word. According to one observer, a typical small town in the East had “temperance negro operas, temperance theaters; temperance eating houses, and temperance everything, and our whole population, in places, is soused head-over-heels in temperance.”

40

the Daughters of Temperance, the Templars of Honor and Temperance, the Colored Temperance Society, and a host of other local, regional, and national organizations dedicated to ridding the United States of alcohol. The ubiquity of the movement was a matter for satirical comment among the majority of Americans who still drank, to whom it seemed that the country was being overrun by the T-word. According to one observer, a typical small town in the East had “temperance negro operas, temperance theaters; temperance eating houses, and temperance everything, and our whole population, in places, is soused head-over-heels in temperance.”

The issue even found its way onboard Yankee ships and penetrated American nautical fiction. In

Moby Dick

(1851) Herman Melville made space for arguments pro and contra temperance, albeit largely contra. The subject was raised under the pretext of a discussion as to what was the correct refreshment for a harpooner, while he was guarding the carcass of a whale against sharks. When Dough-Boy, the cabin steward in the book, produces ginger tea for just such an occasion, he is assaulted by the ship’s mate:

Moby Dick

(1851) Herman Melville made space for arguments pro and contra temperance, albeit largely contra. The subject was raised under the pretext of a discussion as to what was the correct refreshment for a harpooner, while he was guarding the carcass of a whale against sharks. When Dough-Boy, the cabin steward in the book, produces ginger tea for just such an occasion, he is assaulted by the ship’s mate:

“We’ll teach you to drug a harpooneer; none of your apothecary’s medicine here; you want to poison us, do ye? You have got out insurances on our lives and want to murder us all and pocket the proceeds, do ye?”

“It was not me,” cried Dough-Boy, “it was Aunt Charity that

brought the ginger on board; and bade me never give the harpooneers any spirits, but only this ginger-jub—so she called it.”

“Ginger-jub! you gingerly rascal! take that! and run along with ye to the lockers, and get something better . . . it is the captain’s orders—grog for the harpooneer on a whale.”

While Americans were being depicted in fiction squabbling over temperance in the distant whaling grounds, at home its proponents continued to press for legislation at the state level. In 1855 they succeeded in persuading the voters of Maine to ban the manufacture or sale of alcohol for public consumption. This partial prohibition, which had little effect on the drinking of its inhabitants, may be seen as both a public demonstration of virtue and a concession to a fad. Thirteen other states in the Northeast and Midwest followed suit, as did counties in various others. The impact of such laws was varied, as were their provisions. Maine voters were free to import as much liquor as they wished and might also take advantage of exemptions for cider, and alcohol for medicinal use. Pennsylvania limited its prohibition to sales of less than a quart of any alcoholic beverage at a time; Michigan, in order to placate its German immigrants, exempted “beer and wine of domestic manufacture.” Its legislators were pilloried for preferring votes to morality by the Reverend J. S. Smart in his

Funeral Sermon of the Maine Law and Its Offspring in Michigan

(1858): “It is a pity that a few drunken Germans should be allowed thus to rule the thousands of American born citizens in our state. Here, to secure the votes of a few foreigners . . . we have imposed upon us the legal reopening of thousands of dens of drunkenness in the form of ‘Dutch wine halls’ and ‘lager beer saloons.’”

Funeral Sermon of the Maine Law and Its Offspring in Michigan

(1858): “It is a pity that a few drunken Germans should be allowed thus to rule the thousands of American born citizens in our state. Here, to secure the votes of a few foreigners . . . we have imposed upon us the legal reopening of thousands of dens of drunkenness in the form of ‘Dutch wine halls’ and ‘lager beer saloons.’”

The intransigence of immigrant voters was not the only obstacle temperance reformers faced at the polls. American elections were notoriously wet events. Just as Athenian citizens in the days of Plato had received free wine on important civic occasions, so American voters were rewarded by candidates to office for participating in the ballot with as much whiskey as they could hold. The association of alcohol with elections stretched back to colonial days. It derived from Britain, where it had long been customary to treat voters with food and drink. The custom was continued in America, notably in Virginia, where failure to intoxicate potential voters was regarded as mean-spirited in a candidate and therefore a sign that they were unsuitable for public office. An indication of the importance of alcohol to colonial elections is provided by the entertainments bill run up by George Washington in 1758 when he stood for office for the first time in the Virginia House of Burgesses:

Dinner for your Friends £3 0s 0d

13 gallons of Wine at 10/ £6 15s 0d

3 pts of brandy at 1 ⁄ 3 £4s 4d

13 gallons of Beer at 1 ⁄ 3 16s 3d

8 qts Cyder Royal at 1⁄6 12s 0d

30 gallons of strong beer at 8d £1 0s 0d

1 hhd and 1 barrel of Punch, consisting of 26 gals.

Best Barbados rum at 5/ £6 10s 0d

12 lbs S. Refd. sugar at 1⁄6 18s 9d

10 Bowls of Punch at 2/6 each £1 5s 0d

9 half pints of rum at 7d each £0 5s 7d

1 pint of wine 30 1s 6d

13 gallons of Wine at 10/ £6 15s 0d

3 pts of brandy at 1 ⁄ 3 £4s 4d

13 gallons of Beer at 1 ⁄ 3 16s 3d

8 qts Cyder Royal at 1⁄6 12s 0d

30 gallons of strong beer at 8d £1 0s 0d

1 hhd and 1 barrel of Punch, consisting of 26 gals.

Best Barbados rum at 5/ £6 10s 0d

12 lbs S. Refd. sugar at 1⁄6 18s 9d

10 Bowls of Punch at 2/6 each £1 5s 0d

9 half pints of rum at 7d each £0 5s 7d

1 pint of wine 30 1s 6d

In return for such extravagance, Washington was elected with 307 votes. His supporters received, on average, a pint of rum, a pint of beer, and a glass of wine each.

41

This method of encouraging voters continued postindependence, indeed, gained fresh momentum, for the American states had larger franchises, and more frequent elections, than anywhere else in the world at the time. And far from casting their vote in accordance with their convictions or consciences, citizens tended to give them away to inappropriate candidates on the spur of the moment for a few drinks.

41

This method of encouraging voters continued postindependence, indeed, gained fresh momentum, for the American states had larger franchises, and more frequent elections, than anywhere else in the world at the time. And far from casting their vote in accordance with their convictions or consciences, citizens tended to give them away to inappropriate candidates on the spur of the moment for a few drinks.

As the republic aged, the tie between free drinks and the ballot box grew stronger. Voters expected to be treated, and candidates budgeted accordingly. The tie was introduced to new states as they joined the union, as a kind of patriotic institution. In Kentucky, for example, where temperance, in theory, was rampant, King Alcohol still ruled at election time, as the following account of the 1830 polls, from the

New England Weekly Review,

illustrates:

New England Weekly Review,

illustrates:

An election in Kentucky lasts three days, and during that period whiskey and apple toddy flow through our cities and villages like the Euphrates through ancient Babylon. . . . In Frankfort, a place which I had the curiosity to visit on the last day of the election, Jacksonianism and drunkenness stalked triumphant—“an unclean pair of lubberly giants.” A number of runners, each with a whiskey bottle poking its long neck from his pocket, were busily employed bribing voters, and each party kept a dozen bullies under pay, genuine specimens of Kentucky alligatorism. . . . I barely escaped myself. One of the runners came up to me, and slapping me on the shoulder with his right hand, and a whiskey bottle in his left, asked me if I was a voter. “No,” I said. “Ah, never mind,” quoth the fellow, pulling a corncob out of the neck of the bottle, and shaking it up to the best advantage. “Jest take a swig at the cretur and toss in a vote for Old Hickory’s boys.”

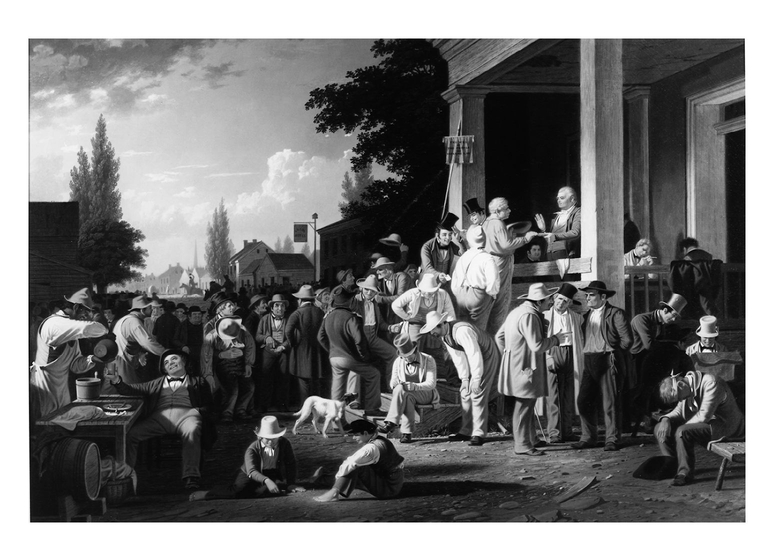

George Caleb Bingham’s

County Election

County Election

“Old Hickory” was President Andrew Jackson, whose election campaign had taken alligatorism to new heights. Its manager, Martin Van Buren, a New York politician and power broker, was a master of promotion. Posters of his candidate were distributed across the country and reproduced in local newspapers. Speechwriters and speech makers were hired to refine their message and preach it through the states. The nickname “Old Hickory” was invented, and thousands of miniature hickory sticks were given away at rallies, in addition to sashes, badges, and the customary drinks. When Jackson won, his supporters descended on Washington in their hordes to attend his inauguration. Thirty thousand accompanied him to the Capitol and did their best to follow him into the White House. Those who had succeeded were lured back outside onto the lawn with barrels of whiskey and bowls of orange punch. For months after, Washington was crowded with a host of men from the backwoods, who very quickly drank it dry of booze, while they waited to be given government appointments as rewards for their votes. Most were disappointed—there were not enough minor posts to go around. However, in the higher echelons of the administration, there were sufficient sinecures to satisfy Van Buren and his coterie, who removed sitting officials and took their places for themselves, justifying their venality with the motto, coined by one of their number, “To the victors belong the spoils of the enemy.”

The affair between drink and American politics peaked in the election campaign of 1840, when General William Henry Harrison, victor of a frontier skirmish, took on the Democratic Party, which had selected Van Buren as its candidate, at its own game. Armed with the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” which referred to the place of his victory, and the name of his running mate, Harrison’s campaigners set out to sing the praises of their candidate to the nation. Scarcely had they commenced when their opponents, intending to denigrate, provided them with a more compelling theme. Van Buren labeled Harrison the “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” candidate, expecting that the electorate would associate these things with squalor and inebriation. He was wrong. Americans held both cabins and cider in high regard and responded enthusiastically when the Harrison campaign gave out models of one, and gallons of the other, at its rallies. Voters liked the themes of self-sufficiency and the simple life apparent in these symbols of frontier life and deemed anyone who criticized them effete:

Let Van from his coolers of silver drink wine,

And lounge on his cushioned settee;

Our man on his buckeye bench can recline.

Content with hard cider is he.

And lounge on his cushioned settee;

Our man on his buckeye bench can recline.

Content with hard cider is he.

Harrison won by a slender margin of the popular vote. He celebrated his arrival at the White House with some cider, and many other drinks, and died of pneumonia after a month in office.

20 WEST

Notwithstanding the lusty drinking that went on during American elections, they were models of restraint and probity in comparison to the democratic process in Mexico. In 1821, America’s southern neighbor had followed it in throwing off the colonial yoke but, rather than organizing itself as a republic, had chosen to be headed by an emperor. Constitutional imperial rule was rejected in favor of a dictatorship two years later, the first of many changes in government that were to enliven Mexican politics for the rest of the century. Twenty-five years after its declaration of independence, a traveling English mercenary estimated that the country had had 237 revolutions over the same period of time.

Excitement in the political sphere was counterbalanced by stability in drinking habits. In order to protect its exports, Spain had maintained severe restrictions on the production of wine and spirits in Mexico almost to the end of its rule, with the consequences that most wine was imported, and most spirits were moonshine. The principal legal drink in Mexico, in terms of volume consumed, was pulque, the favorite moon juice of 2-Rabbits. It was still prepared in a more or less Aztec manner, still spoiled quickly, and its consumption was concentrated in towns. It had come to be perceived of as a type of food, in particular for pregnant women, who were exhorted always to drink at least two cups—one for themselves and one for the child inside them. Pulque was also provided to nursing infants, in the belief that it nourished and strengthened them. This new role had diminished its reputation as an intoxicant and it had become a beverage that anyone, of every age, might enjoy at any time.

Those Mexicans wishing to become their rabbits now drank mescal, i.e., distilled pulque. This was the most common alcoholic beverage in mining communities, and also on the country’s vast ranches and in the little villages that grew up to serve them. The rancheros produced mescal for much the same reasons as Kentucky settlers made whiskey: Distillation concentrated their harvest, extended its life, and rendered it transportable. They took pride in their stills and competed in the quality of their product, to which they attributed medicinal as well as organoleptic properties. Mescal was considered good “for everything bad, and for everything good as well.” The production of this panacea was concentrated in Jalisco, which had become an official part of independent Mexico in 1821. Jalisco was home to the first licensed mescal distillery in the Americas, founded by José Antonio Cuervo, who had received permission from the Spanish crown to distil “mescal wine” in 1795. Its products, and those of the multitude of other stills that sprang up postindependence, were drunk principally by men, who were expected to comport themselves with courtesy and dignity when under the influence. Mescal was used for ceremonial as well as recreational purposes. The Mexicans had kept many of their pre-Columbian festivals alive in the guise of Christian fiestas, the most important of which were Los Días de Muertos (the days of the dead), staged under the cover of the Catholic festivals of All Souls and All Saints. The dead were assumed to return to the world of the living for the duration of Los Días de Muertos and were supplied with offerings of food and drink. Spirits were the most popular libations, and their tendency to evaporate when left out in a glass was interpreted as proof that the departed had taken a sip.

Other books

Redeem The Bear by T.S. Joyce

Hidden ( CSI Reilly Steel #3) by Hill, Casey

King's Crusade (Seventeen) by Starrling, AD

Kaden (Recherché series) by Brit Lauren

Night Rounds by Helene Tursten

Honest Cravings by Erin Lark

A Little Stranger by Candia McWilliam

Unveiling the Bridesmaid by Jessica Gilmore

After the Storm by Sangeeta Bhargava

Trigger Gospel by Harry Sinclair Drago