Drink (47 page)

Authors: Iain Gately

While the debate raged between gourmands and decadents as to the true purpose of wine, the single most important breakthrough in humanunderstanding of alcoholic drinks—a complete and accurate scientific explanation of why they are alcoholic—was achieved in France. The genius responsible for the advance was Louis Pasteur. Prior to his definitive studies, no one in history had been able to describe precisely how grape juice turned into wine. For all they knew, it might have been the invisible hand of Bacchus or some other form of divine intervention. Pasteur made his breakthrough by building on the work of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, the father of modern chemistry, who had discovered that the process of fermentation consisted of the conversion of carbohydrates to carbon dioxide and ethanol, which he named alcohol, thereby introducing the Arabic name for the substance to the West. Unfortunately, his research was carried out at the height of the French Revolution, and as Lavoisier was a tax collector as well as a scientist, his career was cut short by the guillotine in 1794. An appeal for clemency on the grounds of his exceptional discoveries was fruitless. “The Republic has no need of geniuses,” observed the court, and beheaded him the same day.

47

47

The next step toward understanding fermentation was taken in 1836 by a German physiologist, Theodor Schwann. Schwann determined that yeast was a microorganism, named it

Saccharomyces

—Latin for sugar fungus, after its eating habits—and noted that it excreted alcohol after consuming its favorite food. The final breakthrough came in 1862, when Pasteur combined his predecessors’ discoveries and demonstrated that it was yeast that converted the sugars in wine and beer to alcohol. For the first time in history, vintners and brewers understood the magic behind their products. Pasteur conducted further, specific research for each trade, published as

Études sur le vin

(1866) and

Études sur la bier

(1871). Each of these studies addressed the issue of quality control—why certain batches of wine or beer went bad, and how this might be foreseen and prevented. The answer in most cases was bad yeast, or bacterial contamination. To combat the latter, Pasteur invented the process that bears his name—pasteurization. Simply stated, pasteurization involves heating a liquid to sixty-four degrees Celsius for thirty-two minutes, which kills any bacteria it may contain, and if the liquid is subsequently sealed hermetically no microbial activity will reoccur.

Saccharomyces

—Latin for sugar fungus, after its eating habits—and noted that it excreted alcohol after consuming its favorite food. The final breakthrough came in 1862, when Pasteur combined his predecessors’ discoveries and demonstrated that it was yeast that converted the sugars in wine and beer to alcohol. For the first time in history, vintners and brewers understood the magic behind their products. Pasteur conducted further, specific research for each trade, published as

Études sur le vin

(1866) and

Études sur la bier

(1871). Each of these studies addressed the issue of quality control—why certain batches of wine or beer went bad, and how this might be foreseen and prevented. The answer in most cases was bad yeast, or bacterial contamination. To combat the latter, Pasteur invented the process that bears his name—pasteurization. Simply stated, pasteurization involves heating a liquid to sixty-four degrees Celsius for thirty-two minutes, which kills any bacteria it may contain, and if the liquid is subsequently sealed hermetically no microbial activity will reoccur.

In 1867, shortly after Pasteur had revealed the secret processes that gave wine its voice, Paris staged another Universal Exhibition. The city had been extensively remodeled since 1855, under the guidance of Baron Haussmann, prefect of the Seine Department. Haussmann had envisaged Paris “as a perfectly regulated instrument . . . free of traffic jams or slums.” His grand motif was the boulevard, and under his direction Paris received two hundred kilometers of new streets, many of them broad avenues, “lined by 34,000 new buildings containing 215,000 new apartments.” There were changes below as well as above boulevard level. Paris was equipped with piped water delivered via a chain of aqueducts from sources up to 235 kilometers away. Its sewerage system was revamped, and the fetid smells that had characterized the city since medieval days were banished into history.

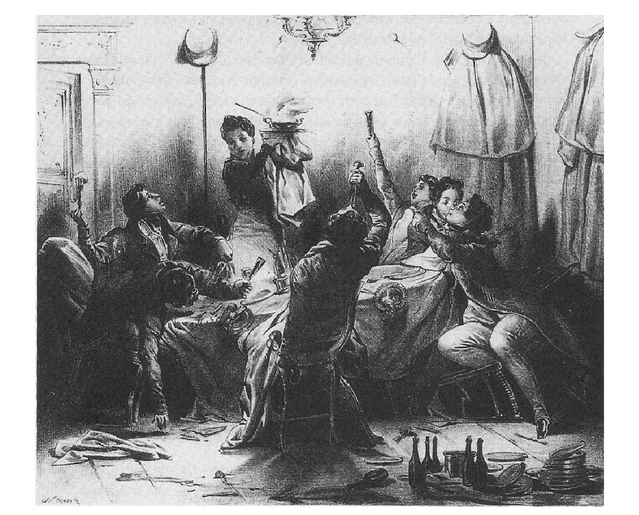

How young people study law in Paris

While some visitors to the exhibition of 1867 enjoyed guided tours of the new waterworks, more put time aside for a trip to one of the capital’s famous restaurants. The temples of

gourmandisme

had become celebrated in foreign guidebooks as cultural landmarks, on a par with Notre Dame and the Louvre, with the advantage over such venerable rivals that they required no more than a good appetite to appreciate. For many American visitors, they also possessed a novelty value. While the first French-style restaurant (Delmonico’s, run by two Swiss Italians) had opened in New York in the 1820s, there were as yet few imitators, and the concepts of choosing one’s meal and eating it at a leisurely pace, with wine, were alien to most Americans. When they crossed this cultural divide in Paris, they wrote agitated letters home. The presence of women, and even children, in restaurants was a common topic in such correspondence. Could this be proper? The American institution that most resembled a French restaurant was a gambling-house-cum-bordello in the West, and it was hard to imagine respectable women, or children of any condition, in such establishments. Such qualms were not entirely unjustified. Savoir faire dictated that one passion leads to another, and Parisian restaurants usually offered

cabinets

—private dining rooms, which ranged in size from cubicles to spaces capable of seating several dozen people—where customers might indulge what Brillat-Savarin termed the sixth sense—the urge to procreate—over lunch, or dinner. Cabinets also served as chapels of drunkenness for the students of the city, whose dedication to wine, whether as apostles of science or Baudelaire, was caricatured in satirical magazines of the age.

gourmandisme

had become celebrated in foreign guidebooks as cultural landmarks, on a par with Notre Dame and the Louvre, with the advantage over such venerable rivals that they required no more than a good appetite to appreciate. For many American visitors, they also possessed a novelty value. While the first French-style restaurant (Delmonico’s, run by two Swiss Italians) had opened in New York in the 1820s, there were as yet few imitators, and the concepts of choosing one’s meal and eating it at a leisurely pace, with wine, were alien to most Americans. When they crossed this cultural divide in Paris, they wrote agitated letters home. The presence of women, and even children, in restaurants was a common topic in such correspondence. Could this be proper? The American institution that most resembled a French restaurant was a gambling-house-cum-bordello in the West, and it was hard to imagine respectable women, or children of any condition, in such establishments. Such qualms were not entirely unjustified. Savoir faire dictated that one passion leads to another, and Parisian restaurants usually offered

cabinets

—private dining rooms, which ranged in size from cubicles to spaces capable of seating several dozen people—where customers might indulge what Brillat-Savarin termed the sixth sense—the urge to procreate—over lunch, or dinner. Cabinets also served as chapels of drunkenness for the students of the city, whose dedication to wine, whether as apostles of science or Baudelaire, was caricatured in satirical magazines of the age.

While the French carried off prizes for wine and luxury goods at the Universal Exhibition of 1867, they lagged in other categories, notably industrial machinery and weapons. The steel artillery pieces exhibited by Krupp, a Prussian firm, were emblematic of the difference in focus between pleasure-loving France and military-minded Prussia. Three years after the exhibition, the same brand of howitzers that had been displayed in Paris were employed against the French capital at the conclusion of a brief but decisive Franco-Prussian War, which established the Prussians as the major land power in Europe, at the head of a unified Germany.

48

The

Second German Empire,

which was constituted in Versailles shortly before France surrendered, was a novelty. From the Dark Ages to the Napoleonic Wars, Germany per se had been a patchwork of independent kingdoms. In order to inspire a sense of nationalism in the citizens of the new entity, it was necessary to invent them a common identity. Prussian concepts of what it meant to be German were used to shape the new ideal.

48

The

Second German Empire,

which was constituted in Versailles shortly before France surrendered, was a novelty. From the Dark Ages to the Napoleonic Wars, Germany per se had been a patchwork of independent kingdoms. In order to inspire a sense of nationalism in the citizens of the new entity, it was necessary to invent them a common identity. Prussian concepts of what it meant to be German were used to shape the new ideal.

Beer drinking was high on their list. It had been confirmed as a Teutonic trait by the hero of Prussian militarism, King Frederick the Great (d. 1786), who had set out his views on the matter in his

“Coffee and Beer” Manifesto

of 1777, which was intended to dissuade Prussians from drinking infusions instead of brews: “His Majesty was brought up on beer and so were his ancestors and his officers. Many battles have been fought and won by soldiers nourished on beer, and the king does not believe that coffee-drinking soldiers can be depended on to endure hardship or to beat his enemies.” Moreover, beer drinking was a pan-Germanic pastime. Bavaria, once Prussia’s greatest rival for Teutonic hegemony, had spent much of the nineteenth century developing a regional identity centered on beer. Its principal festival, the Oktoberfest, while established to honor the nuptials of King Ludwig I in 1810, had since evolved to become a beer-soaked celebration of Bavarianness. A similar passion for suds was evident in the myriad of smaller states incorporated into the new German Empire. Their collective beer love had been nourished during the Napoleonic Wars, when the French had occupied some of them, forced others into alliances, and set about rearranging their frontiers, laws, roads, and social institutions. The hated new rulers were wine drinkers and this preference had been seized on as a cultural point of difference. In consequence the new model German,

Deutsche Michel,

as he was styled at the time, was defined in part by what he opposed. He was simple, well-natured, and strong, in contrast to the effete and arrogant French. Similarly his diet was plain and nourishing—the antithesis of gastronomy. Michel enjoyed his rude good health from eating sausages and drinking beer, rather than picking at partridge wings and sipping Lafitte.

“Coffee and Beer” Manifesto

of 1777, which was intended to dissuade Prussians from drinking infusions instead of brews: “His Majesty was brought up on beer and so were his ancestors and his officers. Many battles have been fought and won by soldiers nourished on beer, and the king does not believe that coffee-drinking soldiers can be depended on to endure hardship or to beat his enemies.” Moreover, beer drinking was a pan-Germanic pastime. Bavaria, once Prussia’s greatest rival for Teutonic hegemony, had spent much of the nineteenth century developing a regional identity centered on beer. Its principal festival, the Oktoberfest, while established to honor the nuptials of King Ludwig I in 1810, had since evolved to become a beer-soaked celebration of Bavarianness. A similar passion for suds was evident in the myriad of smaller states incorporated into the new German Empire. Their collective beer love had been nourished during the Napoleonic Wars, when the French had occupied some of them, forced others into alliances, and set about rearranging their frontiers, laws, roads, and social institutions. The hated new rulers were wine drinkers and this preference had been seized on as a cultural point of difference. In consequence the new model German,

Deutsche Michel,

as he was styled at the time, was defined in part by what he opposed. He was simple, well-natured, and strong, in contrast to the effete and arrogant French. Similarly his diet was plain and nourishing—the antithesis of gastronomy. Michel enjoyed his rude good health from eating sausages and drinking beer, rather than picking at partridge wings and sipping Lafitte.

The Napoleonic rearrangement of Germany had influenced not just the prejudices of its inhabitants but also its brewing industry. Local feudal and ecclesiastic privileges were abolished, petty rulers were stripped of their wheat-beer monopolies in addition to their titles and kingdoms, and the monasteries were disbanded and their breweries sold to merchants. Market liberalization continued after the defeat of Napoléon, and in 1834 Prussia had formed a

Zollverein,

or customs union, with Bavaria and Württemberg, which reduced or removed tariffs on trade between its parties, and constituted the first step toward political union. The Zollverein was expanded in 1836 and again in 1838, and beer flowed across the old borders between German states. In the absence of medieval restrictions and import duties, small and inefficient breweries could not compete with larger better-capitalized operations, and their number declined. Munich, for example, which had had sixty breweries in 1790, had only thirty-five in 1819 and fifteen in 1865. The fewer survivors serviced larger markets. For the first time in centuries they could export to neighboring states and beyond. Concurrent advances in distribution—better roads with fewer tolls, and railways, encouraged the trend. The first freight to be carried by rail in Germany consisted of two casks of beer, which were transported from Nuremberg to Fürth on July 11, 1836.

Zollverein,

or customs union, with Bavaria and Württemberg, which reduced or removed tariffs on trade between its parties, and constituted the first step toward political union. The Zollverein was expanded in 1836 and again in 1838, and beer flowed across the old borders between German states. In the absence of medieval restrictions and import duties, small and inefficient breweries could not compete with larger better-capitalized operations, and their number declined. Munich, for example, which had had sixty breweries in 1790, had only thirty-five in 1819 and fifteen in 1865. The fewer survivors serviced larger markets. For the first time in centuries they could export to neighboring states and beyond. Concurrent advances in distribution—better roads with fewer tolls, and railways, encouraged the trend. The first freight to be carried by rail in Germany consisted of two casks of beer, which were transported from Nuremberg to Fürth on July 11, 1836.

In order to win and keep customers in a free market, German brewers needed to produce a consistent, stable product. To this end they embraced advances in science and technology. The malting process was improved by the introduction of indirect hot-air kilns that dried the grain with warm dry air instead of smoke, which tainted it with combustion residues. They bought thermometers and hydrometers and kept a close eye on innovations overseas. When an Australian named James Harrison constructed a refrigeration device for a brewery in Sydney in 1851, the Spaten Brewery in Munich followed suit a few years later with a “cold machine,” the forerunner of the modern refrigerator. Temperature control enabled German brewers to focus on lager beer, whose bottom-fermenting yeasts work best close to the freezing point and which, hitherto, they had only been able to brew with confidence in the winter months.

German lager was improved by the use of recipes from Czechoslovakia and Austria. Principal among these was

pilsner,

which had been created in the Czech city of Plzen by a Bavarian brewmaster named Josef Groll in 1842. Pilsner

49

was brewed with Saaz hops, soft water, and German bottom-fermenting yeast and was a pale, dry beer with a delicate flavor. The town of České was thought to produce the best Pilsner beer, known as

Budvar

in Czech and

Budweiser

in German. This ambrosia seems to have had a particular appeal to aristocratic households and acquired the nickname “the beer of kings” in recognition of its hold on stately palates. Its name was Germanicized to pilsener, or pils, after its adoption by the Prussians and its quality enhanced yet further with the invention, in 1878, of the beer filter. The end result was a dry, clear golden brew, served chilled, and manufactured in accordance with a centuries-old purity law

50

and new Prussian-inspired legislation imposing national quality standards.

pilsner,

which had been created in the Czech city of Plzen by a Bavarian brewmaster named Josef Groll in 1842. Pilsner

49

was brewed with Saaz hops, soft water, and German bottom-fermenting yeast and was a pale, dry beer with a delicate flavor. The town of České was thought to produce the best Pilsner beer, known as

Budvar

in Czech and

Budweiser

in German. This ambrosia seems to have had a particular appeal to aristocratic households and acquired the nickname “the beer of kings” in recognition of its hold on stately palates. Its name was Germanicized to pilsener, or pils, after its adoption by the Prussians and its quality enhanced yet further with the invention, in 1878, of the beer filter. The end result was a dry, clear golden brew, served chilled, and manufactured in accordance with a centuries-old purity law

50

and new Prussian-inspired legislation imposing national quality standards.

While beer took precedence over wine in the German psyche, German winemaking also flourished throughout the nineteenth century. The Prussian-inspired Zollverein stimulated the art of viticulture as well as that of brewing. Free trade encouraged growers to focus on quality, and German wines began to impress visiting gourmands, who had hitherto believed them (with a few glorious exceptions) to be weak, thin, and acidic. By the time that André Jullien, the pioneer sommelier, toured Germany in the 1840s, he was able to advise his fellow countrymen that change was afoot. Some of its vintages possessed a remarkable bouquet, “equaling, if not surpassing, that of our best wines,” and good or bad, all had the virtue of being weak so that they did not “attack the nerves or trouble the reason when one has drunk too much.”

The improvements Julien had noted were most in evidence in the Rheingau region, whose vintners had discovered the beneficial powers of the noble rot

(Botrytis cinerea)

—a fungus that shrivels grapes and ferments their juices while they are still on the stalk, and which imparts sweet flavors to their wines. Some Rheingau wines were made with hand-selected bunches of such grapes, and the best were pressed from berries chosen individually. These delicacies sent those lucky enough to drink them into raptures. Agoston Haraszthy sampled some on his fact-finding visit to Europe in 1861 and confessed that “to describe [them] would be a work for Byron, Shakespeare, or Schiller, and even those geniuses would not do full justice until they had imbibed a couple of glasses. . . . As you take a mouthful and let it run drop by drop down your throat, it leaves in your mouth the same aroma as a bouquet of the choicest flowers will offer to your olfactories.”

(Botrytis cinerea)

—a fungus that shrivels grapes and ferments their juices while they are still on the stalk, and which imparts sweet flavors to their wines. Some Rheingau wines were made with hand-selected bunches of such grapes, and the best were pressed from berries chosen individually. These delicacies sent those lucky enough to drink them into raptures. Agoston Haraszthy sampled some on his fact-finding visit to Europe in 1861 and confessed that “to describe [them] would be a work for Byron, Shakespeare, or Schiller, and even those geniuses would not do full justice until they had imbibed a couple of glasses. . . . As you take a mouthful and let it run drop by drop down your throat, it leaves in your mouth the same aroma as a bouquet of the choicest flowers will offer to your olfactories.”

The general trend toward the production of superior wines in Germany was further encouraged through the foundation of a wine school at Geisenheim and the creation of model German wineries near Trier. These latter concentrated on producing a dry Riesling, whose flavors became more subtle and delicate as it aged. By the time that the Second German Empire celebrated its tenth birthday, its inhabitants could celebrate their patriotism with perhaps the best beer in the world, and wine manufactured to the most fastidious of standards.

Other books

Moving On (Dominant Devils Mc Book 1) by H.M. Stewart

The Hunter From the Woods by Robert McCammon

Lethal Force by Trevor Scott

Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born: Ian Fleming's Jamaica by Matthew Parker

90 Minutes in Heaven by Don Piper

The Fall of America: Winter Ops by W.R. Benton

Turned to Stone by Jorge Magano

Down Weaver's Lane by Anna Jacobs