Dublin Folktales (10 page)

Authors: Brendan Nolan

There is a monument to her on Grafton Street. Although the cart depicted in the monument is a hand cart and not a barrow, and her low-cut dress would cause her to contract pneumonia in Dublin’s moist climate, Molly it seems, is in Dublin to stay. One thing is sure, she is already generating more Dublin folk tales just by standing there in all weathers, rain or shine, like a true Dublin street seller. For a start, she was conferred with the soubriquet of the Tart with the Cart, though few enough citizens actually call her that, preferring instead to call it the Molly Malone Statue. The actual sculpture was commissioned by Dublin City Council in their millennium year of 1988. The commission was granted in July of that year to the sculptor Jeanne Rynhart for completion and installation by late December. To guarantee a perfect result in the limited time-scale available, two heads were simultaneously prepared from the original mould. Both castings were successful.

Some twenty-three years later, in June 2011, the spare head of Molly Malone, a bronze bust measuring 22in by 15in, was offered for sale at auction in a Castlecomer art salesroom with a guide price of between €20,000 and €30,000. It was not sold on the day. So, not only is Molly said to have lived in two different centuries or not at all, her

statue has a spare head, for the time when she might lose the head she has, if the argument goes on for much longer.

One thing is certain, the sound of the song being sung is like a homing beacon for Dubliners, who don’t really care about the facts, but enjoy a song about one of their own. Molly Malone, whether she existed or not in the seventeenth or the nineteenth century, is alive-alive-o in the city of Dublin and wherever Dubliners gather together to explain how it is that they speak the best English in the world.

W

AKES AND

H

EADLESS

C

OACHMEN

In the olden times, people in Dublin told stories at wakes, to while away the hours before dawn and internment of the deceased. Poor people were generally buried without much fuss, while richer people were wont to show off their affluence in big funerals, lots of carriages, respectful newspaper coverage and ostentatious memorials. But they were still as dead as the poor people.

Normally, when someone died, it was arranged to have a grave dug and a church service was organised to see off the dead person on their way to the next world. Nowadays, the corpse is generally brought to a funeral home where viewing of the remains is facilitated. In older times, people could not afford such luxury and the person was laid out in their own home with the assistance of neighbours who were versed in the niceties of respect for the dead. Stories were shared of other wakes where strange occurrences were seen in the night.

It was said that in parts of Dublin a phantom coach drawn by black horses would come galloping along the street. It would stop outside the wake house and take away any living soul unfortunate enough to be standing there, or foolish enough to wait about for such a thing to happen. Few people could attest to seeing the coach in reality, for if you had, you would be dead yourself. This story was circulated

especially by the sack-’em-ups, as it had the great benefit of keeping people inside the house, where the curtains were already closed out of respect for the recently deceased, and where mirrors were turned to the wall. Closed curtains and empty streets helped the grave robbers to pass along with fresh bodies stolen from any cemetery that had seen a recent interment. This story carried on even when the grave robbers had gone to their own judgement, for a good story will outlast its first telling.

Such considerations matter very little to a man in love with a recently bereaved widow woman. In fact, the ceremonials and sombreness of death can heighten desire, as Andrew was to observe in his amorous pursuit of a dead man’s wife.

Andrew was in love with the recently-bereaved Belinda, who was not paying him an awful lot of attention, on account of the death of her husband Tom. She had been married to Tom for more years than she had thought possible on her wedding day. Tom was a great deal older then she, but, as Tom would joke when demanding she join him on their knees in prayer every night, there was never any prospect of her catching up with him. Belinda did not believe in any religion but she dutifully followed her husband in his nightly devotions because she worked out that if she lived for another five years, and her husband did the same, then she would be rich, for he would surely expire on or before then.

There was neither chick nor child to be considered in disbursement of his fortune. The fortune, which he kept in a box of money beneath their bed, would be Belinda’s and she would be young enough to enjoy it still. In fact, the fortune was the only reason that Belinda had married the man who was as old as her own father. He had come calling to her house when he was growing unsteady on his peasant legs, and needed someone to keep his house neat and tidy, and to prepare his food when he needed it. Belinda, who was not blessed with conventional beauty, agreed to marry him.

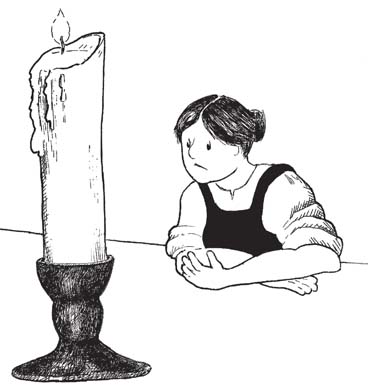

So excited was Tom at the prospect, that he ordered a very large candle from the candlemaker with their names embossed in gold, deep into the wax. He lit this candle every night of their married life, when they knelt down in prayer. In turn, the candle was the recipient of all her disappointment as she watched it flicker before her eyes every evening before the dreary hours of wheezing bed.

There are people living in Ireland who say that when the evil eye is put upon you, you will die no matter what way you twist and turn to avoid it. If so, the evil eye that Belinda placed on her husband Tom came to term when the five years was up. Tom knew his race was run, for he called Belinda in one evening when the prayers were said. He doused the candle by squeezing the burning wick to extinction with his thick fingers.

He said, ‘I am going to have to leave you alone here, soon enough. You have been a faithful companion to me since we wed. For that reason I want you to take the money that I have kept beneath the bed and I want you to enjoy yourself while you live. Buy what you want with it, go wherever you like, but you must promise me one thing.’

She said, ‘Of course, whatever you wish, for you have been a good husband to me in our time together and you have taught me many things.’ But, what he said next shook her deeply, ‘I will wait for you on the far side, no matter how long your time on earth should be. Since we married I have not been with another woman and I know that you have been faithful to me. So as a reward, we will be re-united forevermore in the next life.’

Belinda was a little nonplussed, as one might be at such a proposal, but she agreed for the moment, just in case he had any treasure stored away that she knew nothing about, as he had a great interest in the garden and was forever digging around at the back of the house. Then he said something else that unsettled her further, ‘Take our candle and swear to me that so long as that candle shall burn, you will not allow

your resolve to be swayed by any man.’ This she did, for promising this was worth nothing, and Tom expired more or less the next day.

Neighbours came in and washed the dead man, shaved his stubble and placed his good wedding suit on him. His coffin was placed on their marital bed and a little table was placed at the end of the bed. Candlesticks were loaned by the priest and a saucer of holy water was left on the table near the open coffin where Tom lay sleeping his final sleep. Neighbours came in and commiserated with Belinda, then sprinkled holy water at the dead man while they said a silent prayer. Other neighbours made up sandwiches and they were placed on a large table in the back kitchen for visitors to help themselves. Tea was brewing all the time and there were bottles of drink for those that had a thirst on them.

It was at this point that Andrew wandered in to try his luck with the widow. He was a fine-looking chap that could have had his pick of the female population, but when he settled on nobody in particular, local interest waned in attracting him more permanently. This lack of interest on his part was a direct result of Andrew’s fascination with the married Belinda. Standing beside her, he took her hand, in such a way that she was startled at his touch. ‘I’m very sorry for your troubles’, he whispered in a low voice. ‘But I am touched by your quiet beauty and strength. And I wonder if I might call upon you in the days to come when the house is a bit quieter?’ Belinda pulled her hand away from his, ‘How dare you; can’t you see I am in mourning for my late husband?’

‘I can see that,’ he replied. ‘But your beauty of soul is such that I am touched by the thought of calling in and seeing you again. Alone.’ He then stepped away from her. He threw a few drops of holy water in on the mortal remains of Tom in the coffin. They landed on his face and eyes. Tom wandered into the kitchen for some words with the local lads and a drop of whatever was going. Belinda

moved from her place. She opened the high dark-wooded chest of drawers and took out the wedding candle. Other women watched with some interest as she placed the candle firmly on the table beside the coffin. ‘It was Tom’s favourite candle’, she explained as she lit it with a taper from the lesser candles.

As the night drew on, men came from the kitchen and took up their places around the coffin. They were to stand watch through the long hours of night. It was what was done; no corpse lay alone in a Dublin household through the hours of darkness on the night before the funeral. Outside in the kitchen low songs were sung for the consolation and diversion of the living. Memories of the dead man were exchanged and stories were told to celebrate his time among them. A perfect balance between death and life was sought.

There was talk of the headless coachman and the black horses and the phantom coach coming along the road, and drinking continued. Andrew drank his share of a white liquid distilled locally in an informal way by an old neighbour of Tom’s who was skilled in such matters. By the time he rose to leave, he had begun to sway gently. He would walk home, he announced, as he needed to sleep now to fortify himself against what was to come in the future. Nobody paid him much attention for people often speak nonsense in the early hours of the morning at a wake. He saluted all there and he saluted Belinda from the door of the coffin room and turned away.

What happened next became the stuff of legend and was re-told at other funerals.

While Andrew left the house, intact and alive, he was found the following day lying face down on the road two parishes away. He had been hit by a passing truck with only one decent headlight working. He was carried along unbeknownst to the driver who did not know that he had hit Andrew in the dark. Neither was he aware that a body fell out from underneath the lorry as he crossed a hump-backed bridge some distance away. Ever afterwards, people at the wake swore they had heard horses hooves galloping past after Andrew left the house. They said he must have been taken into the coach, fought for his liberty and fallen out at the bridge.

In the bedroom, Belinda, who knew nothing of this, made sure Tom’s candle burned down as swiftly as she could will it to. By dawn, it was guttering away and finally it sputtered out. As it went, she fancied she heard a noise from the bier. She looked at Tom’s face. His face remained as it had been all night, but who knew what the dying candle light had shown as it finally expired.

L

OST

S

HOES

Lack of footwear for children in poor parts of 1940s Dublin led to such a high level of school absenteeism that concerns were raised in the Dáil about the situation. An evening newspaper set up ‘The Herald Boot Fund’ to raise funds for the purchase of footwear for children in the city. Conferences of the St Vincent de Paul Society, the Children’s Clothing Society, the Roomkeepers Society and the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, all joined the effort to shoe the poor.

The problem was not unique to Dublin. Boots were issued by various local councils around the country to the deserving. Such footwear came with a council stamp placed resolutely on the sole of the boot, to prevent profiteering. This lead to major embarrassment, when the wearer knelt down in church and exposed his sole for all behind to see.

Hobnails placed underneath the boots made so much noise that when a troop of boys came along the busy streets of Dublin it was not unlike the sound a small invading army making its way along the thoroughfare. Add in the rattle of ball bearing wheels of numerous handcarts conveying everything from coal, to pig feed, to newspapers and fish for sale, and Dublin was a noisy place. Most families had a hand cart, or access to one, in an era when running a car or van was out of the question for most.

Imagine then the catastrophe facing a teenage Brian Byrne when he lost a new shoe in the river Liffey. The river’s weirs were built to control the level of water on its journey to the sea. Included in their design were salmon chutes to aid spawning salmon on their annual journey upstream. To get to the grassy island, where it was safe to swim, local swimmers walked along the green mossy rounded tops of the weirs. Shoes had to be carried in the hand, trouser legs had to be rolled up, and a balancing act was employed to keep the wandering eye away from the rushing white water of the chute. It was heady stuff, right enough.