Duby's Doctor (36 page)

Authors: Iris Chacon

Tags: #damaged hero, #bodyguard romance, #amnesia romance mystery, #betrayal and forgiveness, #child abuse by parents, #doctor and patient romance, #artist and arts festival, #lady doctor wounded hero, #mystery painting, #undercover anti terrorist agent

“You got it,” said Hepzibah Stoner.

“Snicklebean is history.”

End of Prologue and Sample Chapter

of

SCHIFFLEBEIN’S FOLLY

by

Iris Chacon

Enjoy These

Sample Pages

From

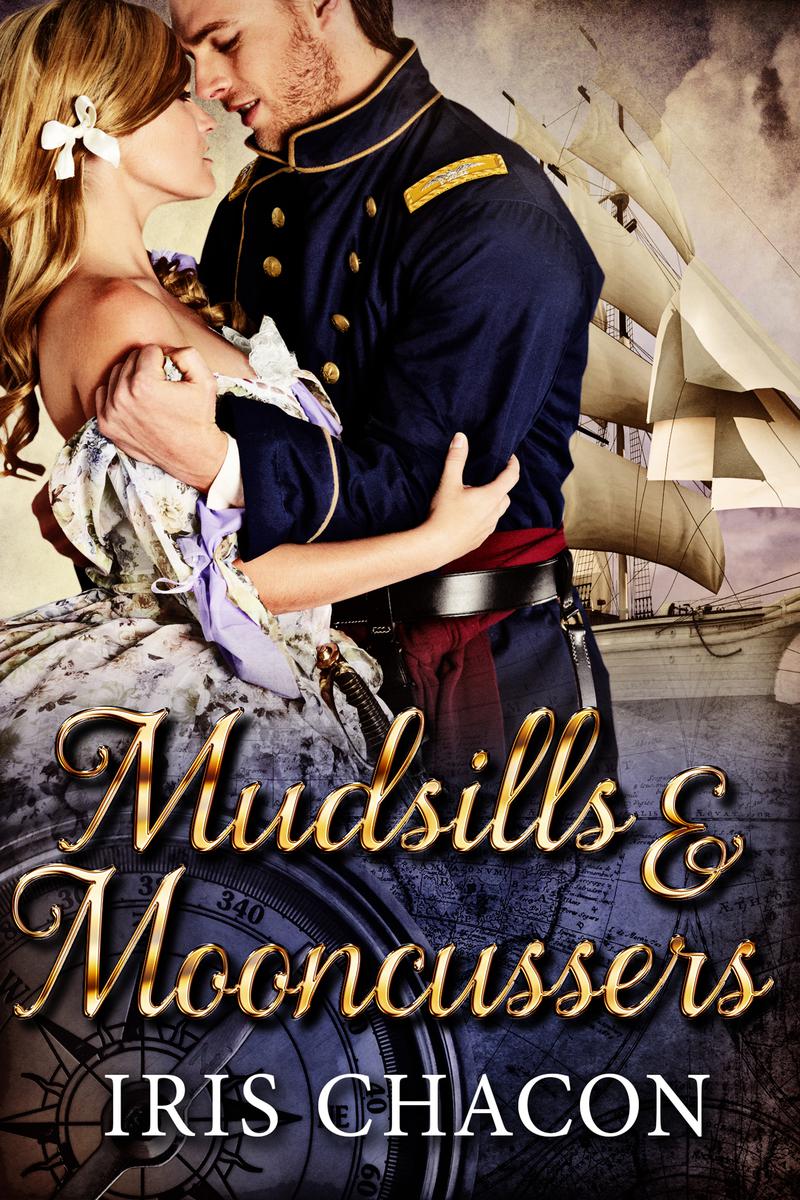

MUDSILLS & MOONCUSSERS

In Key West, the southernmost city in the South

during the War Between the States, Aaron Matthews has the

misfortunate to be a spy for the North. His search for a saboteur

working for the South is further complicated when Aaron realizes

the culprit may be the very woman with whom he is falling in

love.

SAMPLE CHAPTER

1862

Sergeant Jules Pfifer, a career Army man,

marched his patrol briskly through the evening heat toward a tall

wooden house on the corner of Whitehead Street and Duval Street.

Atop the house was perched a square cupola surrounded by the

sailor-carved balustrades called gingerbread. These porches, just

large enough for one or two persons to stand and observe the sea

from the rooftop, were known as widow’s walks. From this particular

widow’s walk an illegal Confederate flag flaunted its red stars and

bars against the clear Key West sky.

The soldiers in Union blue marched smartly

through the gate in the white picket fence, up the front steps, and

in at the front door—which opened before them as if by magic.

“Evenin’, Miz Lowe,” Sergeant Pfifer said,

without breaking stride, to the woman who had opened the door.

“Evenin’, Sergeant,” the lady of the house

answered, unperturbed.

On the Lowe house roof, the stars and bars

were whipped from their post; they disappeared from sight just as

the soldiers, clomping and puffing and sweat-stained, arrived atop

the stairway. Pfifer and another man crowded onto the widow’s walk.

Consternation wrinkled the soldiers’ faces when they found no

Confederate flag, only 17-year-old Caroline Lowe, smiling

sweetly.

~o~ ~o~ ~o~

In the twilight, the three-story brick

trapezoid of Fort Zachary Taylor loomed castle-like over the sea

waves. It stood on its own 63-acre shoal, connected to the island

of Key West by a narrow 1000-foot causeway. The fort had taken 21

years to build and was plagued by constant shortages of men and

material as well as outbreaks of deadly yellow fever.

Yankee sentries paced between the black

silhouettes of cannon pointed seaward. Firefly lights of campfires

and lanterns sparkled on the parade ground and among the Sibley

tents huddled on shore at the base of the causeway.

Midway between the fort and Caroline Lowe’s

flagpole, on the tin roof of a three-story wooden house, behind the

gingerbread railing of another widow’s walk, two athletic, handsome

youngsters stood close together, blown by the wind. Twenty-year-old

Richard scanned the sea with a spyglass. Joe, an inch shorter than

Richard, kept one hand atop a floppy hat the wind wanted to

steal.

Richard found something interesting to the

east. He handed over the spyglass and pointed Joe toward the same

point on the horizon. Joe searched, then zeroed in.

“Some rascal’s laid a false light over on

Boca Chica,” Richard said, referring to the smaller island just

north of Key West. “Come on!”

They tucked the spyglass into a hollow rail

of the widow’s walk and hastened down the stairs.

~o~ ~o~ ~o~

On neighboring Boca Chica island, night

blanketed the beach. A hunched figure tossed a branch onto a

blazing bonfire then slunk away into the darkness. Pine pitch

popped and crackled in the fire, adding its sweet aroma to the tang

of the salty breeze coming off the sea.

~o~ ~o~ ~o~

Inside a warehouse on Tift’s Wharf, all

shapes and sizes of kegs, boxes, and wooden crates towered in

jagged heaps. Sickly yellow light from a sailor’s lantern sent

quivering shadows across the stacks. A spindly boy of 15, Joseph

Porter, kept watch through a crack in the door.

On the floor a dozen teenaged boys hunkered

down, whispering. Richard sneaked in from the rear of the building

to join them. Behind him, out of the light and keeping quiet, came

Joe.

Porter hissed, “Mudsills comin’!”

The whispered buzz of conversation halted.

Someone doused the light. Bodies thumped to the floor as the boys

took cover.

Outside, footsteps ground into the gravelly

dirt of the street. Four Yankee soldiers, the source of the boys’

concern, completed a weary circuit of the dark dockside buildings.

They were Pennsylvania farm boys not much older than the Key West

boys hiding inside.

The southern boys would have been surprised

to know that the Yankees in the street were not technically

“mudsills,” that being the name given to northern factory workers

who lived crowded together in dirt-floored shacks along muddy

streets. Still, the word was applied to all the Yankee enemies,

just as the northern boys would have called Key West residents

“mooncussers,” as if they all were pirates.

Native born citizens of Key West referred to

themselves as Conchs, a term dating back to the 1780s immigration

of British Loyalists from the Bahamas. A large shellfish called a

conch was plentiful in the local waters and became a staple of the

pioneers’ diet.

On Tift’s Wharf one of the Pennsylvania

soldiers said something in Dutch-German, and the others murmured

agreement. They sounded homesick. One slapped a mosquito on his

neck then turned up his collar, grumbling.

In front of the warehouse the soldiers

stopped beside a barrel set to catch rainwater running off the tin

roof during storms. They loosened their woolen tunics and dipped

their handkerchiefs into the water, laving themselves, trying in

vain to ease the steamy agony of tropical heat.

Inside, the wide-eyed Conch boys held their

breath, listening to the sounds from the water barrel outside.

Joseph Porter trembled, perspired, and stared cross-eyed at a

gigantic mosquito making itself at home on the end of his nose. He

tried to raise one hand quietly to chase the brute away, but his

elbow nudged a crate of bottles. Glass tinkled. The boys froze.

Outside, a soldier started at the sound and

snatched up his weapon.

“Vas ist das?”

The other soldiers were less concerned. They

were hot, tired, and not looking for trouble.

“Rats,” one said. “These pirate ships are

full of them. Let’s go back to the ice house. It’s cooler.”

The sweat-covered Conch boys heard the

receding footsteps of the Yankees. Long, sweltering seconds later,

Porter crept to his crack in the door and risked a peek. “It’s all

right. They’re gone.”

Red-haired William Sawyer lit the

lantern.

A bigger boy, Marcus Oliveri, stepped forward

and cuffed Porter smartly. “Porter, you imbecile!”

“Here now, Marcus!” said William. “He didn’t

mean to.”

Oliveri returned to his place in the circle

of boys forming around the lantern. “I don’t fancy getting arrested

or maybe shot because Porter can’t abide getting mosquito bit for

his country!”

“I’m sorry,” said Porter. “It was an

accident.”

“Let’s just forget it,” urged William. “Let’s

finish up and get out of here before they come back. Now, the

English schooner leaves for Nassau tomorrow morning. Richard and

Marcus and Alfred and me will be on it. The rest of you know what

to do to cover for us.”

An older boy with a thick Bahamian accent,

Alfred Lowe, shook his finger under the nose of a friend. “And you,

Bogy Sands, stay away from my sister while I’m gone, you hear

me?”

Richard looked surprised. He thought he and

Caroline Lowe had an unspoken agreement. “Caroline? Bogy!”

“You ain’t engaged to her, Thibodeaux,” said

Bogy.

William Sawyer’s hair flashed the same fiery

color as the lamplight when he reached across the circle to

separate Richard and Bogy. “That’s enough of that! Let’s not be

fighting each other. God willing, we’ll all be soldiers of the

Seventh Florida Regiment within the year. Any questions?”

All around the circle the boys murmured in

the negative.

“Let’s get home then, and be ready when the

call comes,” William said.

The boys scrambled away. Joe and Richard were

the last to leave, watching for Yankee patrols while the others

sneaked out.

Joe complained, “I’ll probably break my neck

walking around in your boots. You got such big feet, Wretched! I

had to stuff the toes with rags.”

“You just keep that hat on and stay out of

Papa’s way. You’ll do fine,” Richard replied.

As they moved to leave the warehouse, Richard

put an arm around Joe’s shoulders and gave an encouraging

squeeze.

~o~ ~o~ ~o~

In the Florida Straits between Key West and

Cuba, just before dawn, two lithe, black fishermen reacted to the

flare of a distress signal that arced upward in the eastern sky.

One fisherman reached into the bilge of his craft and produced the

empty pink-and-white spiraling shell of that large mollusk called a

conch. He lifted the trumpet-size conch shell to his lips and blew

a loud, hooting blast.

Seconds later on Tift’s Wharf, a lookout in a

wooden tower reacted to the distant conch horn, scanned the eastern

horizon with a spyglass for barely an instant, then clanged the

wreckers’ bell and shouted to wake the whole island.

“Wreck asho-o-o-re! Wreck asho-o-o-re!”

Men of all sizes came running from every

direction. Black men and white, old and young, in jerseys and loose

short pants, they raced through the streets of Key West to the

Jamaica sloops moored in the harbor. Every shopkeeper (save one,

William Curry) left his store, every clergyman his church, every

able-bodied homeowner his house. Quickly it became apparent that

nearly every man in Key West, whatever else he might be, was a

wrecker.

Men shouted, the bell clanged, the distant

conch horn trumpeted. The race was on. Yankee soldiers, standing on

the street corner, did well not to be trampled in the rush.

At Fort Taylor, blue-clad soldiers on the

roof of the fort took note of the wreck and watched closely the

activity in the harbor, ready to take action if necessary.

Aboard the moored schooner Lady Alyce,

white-bearded, patriarchal Captain Elias Thibodeaux, regal in his

double-breasted jacket, surveyed the scene with hawk’s eyes. The

Lady Alyce, at 50 feet and 136 tons, was a sleek topsail schooner

with well-greased masts, coiled lines, and shining brightwork. She

looked like she could outsail anything.

“Mister Simmons,” the captain shouted.

The mate, Cataline Simmons, was a black

Bahamian with the muscles and instincts of an experienced sailor

and the accent of an Oxford professor. “Aye, sir!”

Thibodeau’s eyes searched the wharf again,

but it was no use. What he sought was not there. “Hoist the

mains’l,” he commanded.

Cataline, too, looked with concern at the

wharf before executing the order.

“Today, Simmons!” bellowed the captain.

“We’ll leave him if we have to, but I will be first to bespeak that

wreck!”

Cataline leapt into action, gesturing to four

crewmen—three white, one black—who waited poised at their stations.

“Aye, sir! Hoist the mains’l.”

The three white crewmen set about their tasks

quickly, skillfully. The small, wiry black man, Stepney Austin,

hesitated. If Thibodeaux was king here, and he undoubtedly was,

then Stepney Austin was the court jester. Monkeylike in his

movements and Cockney in his speech, he could be the bane of

Simmons’ existence if he were not so brave and loyal.

“Cast off the docklines,” said the

captain.

Cataline threw Stepney a look. Stepney moved

as if he had been waiting for just such an order.

The sail was filling; other boats were

getting underway. Stepney cast off the bow lines and moved

deliberately toward the stern, watching the wharf as did Cataline.

Thibodeaux turned away and looked seaward, giving up on finding

what he sought upon the wharf.

Then Joe, baggy in Richard’s clothing and

unsteady in Richard’s boots, appeared at the far side of the wharf,

running toward the Lady Alyce.

Stepney cried, “There he is!”

Thibodeaux did not look. “Cast off!”

Cataline lifted a cargo block hanging from

the rigging nearby and, as he spoke, swung the block like a great

pendulum out over the wharf. “Casting off. Aye, aye, sir.”

Stepney was forced to comply, but it was in

slow motion that he cast off the stern line.

Joe ran desperately to close the gap of

several yards between Richard’s reluctant boots and the departing

schooner. When the cargo block swung toward Joe, Joe took full

advantage of it by grabbing it and hanging on for dear life.

Stepney chanted, “Come on, come on!”

Joe’s forward motion combined with the

pendulum swing of the block to carry Joe, like a trapeze artist,

across the chasm now yawning between schooner and wharf. Joe landed

more-or-less flatfooted on the deck behind Captain Thibodeaux.

Richard’s floppy hat tumbled from Joe’s head, followed by a cascade

of unruly curls that reached halfway down her back.