Duke (6 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

But there was no way for Washington’s middle-class blacks to ignore their dark-skinned neighbors, try though they might, since both classes were packed into one and a half square miles of crowded city streets. The lives of college professors and (in Hughes’s words) “the ordinary Negroes . . . folks with practically no family tree at all, folks who draw no color line between mulattoes and deep dark-browns” were inescapably intertwined, and an educated black who, like Hughes, felt more at ease among the “ordinary Negroes” who “played the blues, ate watermelon, barbecue, and fish sandwiches, shot pool, told tall tales, looked at the dome of the Capitol and laughed out loud” was never more than a stone’s throw from the buzzing street life of black Washington.

Nowadays it’s harder to see that both sides of this cultural coin have a like claim on our attention, since the popular culture of Hughes’s “ordinary Negroes” long ago prevailed over the genteel culture of U Street’s citizens. To listen to the first recording of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” made in 1909 by the Fisk Jubilee Quartet, whose members hailed from Nashville’s all-black Fisk University, is to be startled by its staidness. You might almost be hearing four gentlemen in high-button shoes warbling close-harmony hymns in the parlor. How to explain their near-Victorian tone? The answer is that the quartet consisted of university men, aspiring members of the middle class. Indeed, the mere fact that they were singing spirituals (instead of, say, part-songs by Brahms) was enough to make some of their fellow students look askance at them. In 1909 spirituals were still widely viewed in the black community, and in Fisk’s own all-classical music department, as quaint relics of the bad old days of slavery. The Jubilee Quartet’s singing of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is polished to a degree that sounds “wrong” to postmodern ears—but does that make it less authentic? In 1983 a surviving member of the quartet told an interviewer that the group “interpreted [spirituals] as the slaves did . . . we were closer to slavery and we got a deeper, an in-depth feeling of that music.”

All of which is another way of saying that black life in turn-of-the-century America was far more complicated than it looks from a distance, and that the politer black musical styles of the period were as “authentic” as the dance-based working-class music that today’s listeners esteem. So, too, do the ambitions of the middle-class blacks of U Street (if not their childish bigotry) deserve to be taken seriously. Even at their most affected, they were trying to live decent lives and make a better world for their children and grandchildren, some of whom, Duke Ellington among them, would go on to do things of which they could only dream.

• • •

What did Ellington think of the city of his childhood and youth? In old age he wrote of it with dewy-eyed affection. Washington, he said, was good to him—but he left it as soon as he could, never again to look back save through the comforting haze of nostalgia.

Here as always, one must read between the lines of

Music Is My Mistress

to get anything useful out of it. On occasion Ellington let slip a few indiscreet words about the realities of life in Washington, admitting that the black community there was divided into “castes” and that “if you decided to mix carelessly with another you would be told that one just did not do that sort of thing.” What he took greater care not to say was that his own parents belonged to the in-between caste that came to be known as the black bourgeoisie. It’s impossible to understand the man whom Ellington became without understanding this fact and its implications, yet he did his best to keep anyone from knowing the whole truth about his young years. Throughout his life he spoke warmly of James Edward Ellington (always known as “J.E.” or “Uncle Ed”) and Daisy Kennedy Ellington, and his praise was fulsome to a fault. What he said has mostly been taken as gospel truth, but there was more—and less—to J.E. and Daisy than their loyal son admitted. While he was more inclined to prettify than lie outright, the result was the same: The Ellingtons of

Music Is My Mistress

are candy-coated caricatures whose goodness beggars belief. The first step in understanding their son is to scrub away the sugar and see his parents as they were.

J.E. was born in North Carolina in 1879 and moved to Washington around 1890. He entered the service of Dr. Middleton F. Cuthbert, whom Ellington described as “rather prominent socially,” at some point between 1894 and 1898, eventually becoming Dr. Cuthbert’s butler. The two men seem to have been on friendly terms: Barry Ulanov, who interviewed Ellington at length for his 1946 biography, described J.E. as the doctor’s “confidant and very close friend.” Not having gotten beyond grade school, he educated himself further by reading the books in the doctor’s private library and acquired hand-me-down dishes and cutlery from other families whose parties he catered. “The way [J.E.’s] table was set,” Duke’s son said, “was just like those at which my grandfather had butlered.”

It would appear that he also picked up Dr. Cuthbert’s high-society manners. Whatever its source, J.E.’s suavity impressed all who met him, starting with his children. Ruth Ellington called him “a Chesterfieldian gentleman who wore gloves and spats.” Her brother’s memories were more specific—and worldly. He was particularly impressed by his father’s fancy turns of phrase, which made their way into his own speech:

I have always wanted to be able to be and talk like my pappy. He was a party man, a great dancer (ballroom, that is), a connoisseur of vintages, and unsurpassed in creating an aura of conviviality. . . . He was also a wonderful wit, and he knew exactly what to say to a lady—high-toned or honey-homey. I wrote a song later with a title suggested by one of those sayings he would address to a lady worth telling she was pretty. “Gee, you make that hat look pretty,” he would say.

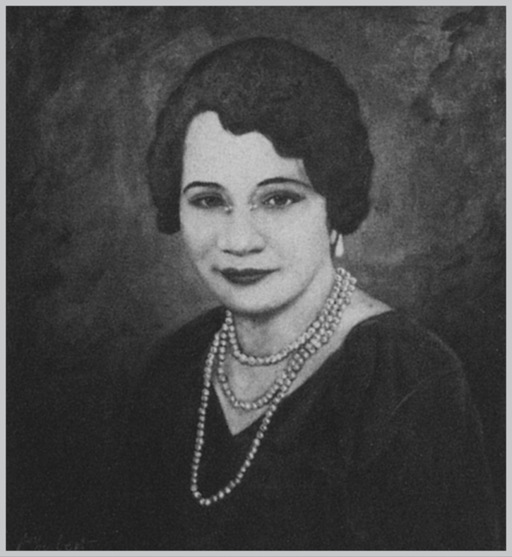

Beautiful and handsome: Family portraits of Daisy Kennedy Ellington and James Edward (J.E.) Ellington. These paintings, which hung in the living room of Duke Ellington’s Manhattan apartment, were seen on national television when he was interviewed by Edward R. Murrow on

Person to Person

in 1957

Daisy was born in Washington in 1879. Her father was a police captain, one of only forty black officers in the District of Columbia, and her grandparents included a white senator and a Cherokee Indian. In black Washington that constituted a good family, far better than that of the man she married. She was a regular churchgoer, and she also seems to have been a prude: Ulanov, possibly following her son’s lead, described her as “stiff-lipped” and “prim of mien and manner.” Her pince-nez and light-colored skin made Daisy’s gentility evident to all who saw her, as did her musical tastes. A competent pianist, she favored salon ballads like Ethelbert Nevin’s “The Rosary,” a favorite of Fritz Kreisler and John McCormack, which made her four-year-old son weep when she played it for him one day.

†

Ulanov believed that “the violently crossed influences of his father and mother” gave the mature Ellington a “startlingly ambivalent” personality that was at once “introspective” and “exhibitionist.” True or not, Daisy and J.E. were an ill-sorted pair—they even went to different churches—and one wonders what her parents made of their decision to marry in 1898. They also appear to have been sexually incompatible: Mercer Ellington said that they “slept apart” after Daisy found out that her husband was having an affair with another woman. Though Ellington says nothing disparaging about either of them in his autobiography, he devotes far more space to Daisy, going so far as to claim, “No one else but my sister Ruth had a mother as great and as beautiful as mine.” What he found most admirable about his father, by contrast, was his smooth-talking savoir faire, which he would endeavor to emulate. J.E., he said, “spent and lived like a man who had money, and he raised his family as though he were a millionaire.” But he wasn’t: J.E. was in service to a white man, and it was only much later that he struck out on his own, first becoming a full-time caterer during World War I and then, in 1920, taking a job as a maker of blueprints at the Navy Yard.

Might Ellington have been embarrassed by his father’s pretensions? If so, he never let on. But a later generation was to take a dimmer view of ballroom-dancing black men who exalted appearance over reality. E. Franklin Frazier, the chairman of Howard University’s sociology department, gave a name to such folk when he published

Black Bourgeoisie,

the still-controversial 1957 study in which he anatomized the “world of make-believe” in which they sought “to escape the disdain of whites and fulfill [their] wish for status in American life.” Malcolm X, born a quarter century after Ellington, wrote with biting contempt in his own autobiography of the lower-tier bourgeoisie of Roxbury, the Boston suburb where he had lived as a boy:

I’d guess that eight out of ten of the Hill Negroes of Roxbury, despite the impressive-sounding job titles they affected, actually worked as menials and servants. “He’s in banking,” or “He’s in securities.” It sounded as though they were discussing a Rockefeller or a Mellon—and not some gray-headed, dignity-posturing bank janitor, or bond-house messenger.

Was that how J.E. looked to the fortunate son who spent a lifetime putting the flesh of achievement on the bare bones of his father’s hand-me-down manners? Or did Ellington prefer to think of him not as a make-believe gentleman in spats but as a dead-earnest striver who played his cards as well as he could? The only clue to be found in the pages of

Music Is My Mistress

is this sibylline sentence: “My mother, as I said before, was beautiful, but my father was only handsome.” It’s tempting to hear in those last two words the judgment of a son on the failings of a parent, but if Ellington ever said anything else to anyone else about J.E.’s failings, it went unrecorded.

• • •

Duke Ellington was a spoiled child, and proud of it. The very first thing that he tells us about himself in

Music Is My Mistress

is that his parents pampered him:

Once upon a time a beautiful young lady and a very handsome young man fell in love and got married. They were a wonderful, compatible couple, and God blessed their marriage with a fine baby boy (eight pounds, eight ounces). They loved their little boy very much. They raised him, nurtured him, coddled him, and spoiled him. They raised him in the palm of the hand and gave him everything they thought he wanted. Finally, when he was about seven or eight, they let his feet touch the ground.

It may seem an odd point for him to make so emphatically, but for once his memoiristic instincts played him true. Not only was he “spoiled rotten,” but the child was father to the man: He arranged his adult life in such a way as to reproduce as closely as possible the way that his parents had treated him as a boy. Born in the home of his maternal grandparents on April 29, 1899, Edward Kennedy Ellington was named after J.E. and Daisy, who thereupon gave him whatever he wanted, as did Daisy’s many female relations. While the fact that their first child had died in infancy helps to explain the favor with which the second was treated, the unremitting intensity of his mother’s love, along with her certainty that he was destined to do well in the world, were a thing unto themselves. Daisy instilled in her son an attitude that might be described as “Ellingtonian exceptionalism,” a doctrine to which he would subscribe forever after. “Edward, you are blessed,” Daisy told him. “You don’t have anything to worry about.” Such love can be smothering, but he was inspired by it. When he descended from his upstairs bedroom to go to school, he would deliver a little speech to his mother and aunt: “This is the great, the grand, the magnificent Duke Ellington. Now applaud, applaud.” He offered multiple explanations of how he acquired his lifelong nickname, but most of them point to his having been dubbed “Duke” by a childhood friend, partly because of his princely manner (the Duke of Wellington’s name would have been known to his playmates) and partly because his mother dressed him so stylishly. Whatever the reason, it fit him well, and the schools that he attended, which taught “proper speech and good manners,” improved the fit still further.