Early Dynastic Egypt (61 page)

culture’ (Seidlmayer 1996b: 118).

Local temples and shrines seem to have been devoid of relief decoration. They were probably built entirely from mudbrick, the monumental use of stone apparently being a royal monopoly in the Early Dynastic period. By contrast, temples founded or ‘usurped’ by the state were either entirely stone built, or, more commonly, embellished with stone

elements. These were carved with relief scenes depicting the rituals of kingship, especially temple foundation ceremonies and the Sed-festival. This essential difference between local and state temples has been summarised as follows:

Evidently, state interests were pursued independently, without acknowledging the temples in their role as indigenous organisational and ideological nuclei of the local communities, and these shrines were not the places the kings chose to display their relationship to the local gods as a tenet basic to their ruling ideology. Consequently, it was felt unnecessary to adorn the provincial sanctuaries with carved and inscribed architectural elements which would have offered the possibility to express such a doctrine in visible and lasting form.

(Seidlmayer 1996b:119)

Temple building

An entry on the Palermo Stone for the reign of Den records the erection

( h )

of an unspecified temple

(hwt-n r),

whilst a label of Qaa from Abydos (Dreyer

et al.

1996:75) is unique amongst year labels of the First Dynasty in that it mentions a building project: the foundation of a building called

q3w-n rw.

The annals suggest that the foundation of a new religious building usually comprised a more elaborate sequence of events. Three different ceremonies—perhaps stages in the process—are recorded on the Palermo Stone for the same temple

swt-n rw,

‘thrones of the gods’, during the reign of Den. The first ceremony seems to have been designated by the word

h3, p

erhaps indicating the initial decision to found a new temple and perhaps the first planning phase (Erman and Grapow 1929:8, definition 4). However, the main Cairo fragment of the royal annals seems to challenge this interpretation since it apparently records a

second

‘planning’ of the

same

building

smr-n rw

in the one reign. The term

h3 m

ay instead refer to a ritual circuit of the building, performed by the king (Gaballa and Kitchen 1969:15; F.D.Friedman 1995:14). The annals also record the crucial ceremony of

p -šs,

‘stretching the cord’, which is customarily shown in temple foundation scenes, such as the relief block from the Early Dynastic temple at Gebelein and the door-jamb of Khasekhemwy from Hierakonpolis. The stretching of the cord represented the formal laying out of the temple, and accompanied the sanctification of the land on which the temple was to be built. A subsequent phase,

wpt-š,

‘opening of the (sacred) lake’, is recorded for the temple ‘thrones of the gods’. For this building, the three ceremonies are recorded for consecutive years. This indicates, perhaps, that the temple was not a particularly large one, since the construction of a major building might be expected to have taken considerably longer. Apparently, it was not necessary to accomplish (or to record) all three ceremonies for every new temple. Early in the First Dynasty, only one ceremony (

h3

) is mentioned for a temple called

smr-n rw,

‘companion of the gods’, whilst in the early Third Dynasty the stretching of the cord seems to have been the initial ceremony in the foundation of the temple

qbh-n rw,

‘refreshment of the gods’.

Early Dynastic shrines

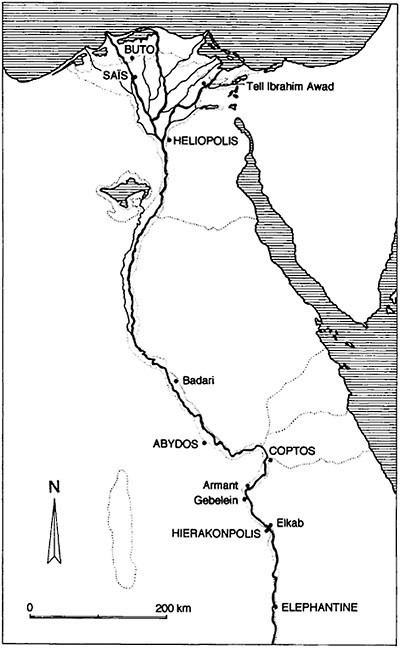

The evidence for early temples is both epigraphic and archaeological (Figure 8.8). Two distinct religious precincts at Buto, a complex with palm trees and the shrine of

b wt,

are well attested in Early Dynastic inscriptions—and throughout Egyptian history—but have not been located at the site itself. Excavations in the main temple area have not, so far, revealed any material older than the New Kingdom. Likewise, the important shrine of Neith at Saïs is known to have existed in the Early Dynastic period but still awaits discovery and excavation. Some early provincial shrines, like those at Tell Ibrahim Awad, Badari, Armant and Elephantine, do not merit a mention in the written record but are known through their surviving archaeological remains, which indicate very modest structures (Kemp 1995:688). In the case of important cult centres such as Heliopolis, Abydos and Hierakonpolis, discoveries through excavation have confirmed the epigraphic evidence for the importance of these sites at an early period of Egyptian history.

Elephantine

‘Elephantine is the only site in Egypt where, thanks to a lucky combination of circumstances, the development of a provincial sanctuary can be followed from protodynastic times onwards’ (Seidlmayer 1996b: 115). The earliest shrine on the island of Elephantine has been uniquely preserved, thanks to its unusual location. It was situated in a natural niche between a group of large boulders, to the north of the early settlement. Successive rebuildings and enlargements required more space, and so filled in the site of the early shrine, building over the top of the boulders. The structure of the Early Dynastic temple and many of the votive objects deposited there survived (Dreyer 1986; Kemp 1989:69–74). The first structure to be built comprised two small mudbrick chambers, which appear to have been designed to protect and shield the sanctuary holding the cult image. This was presumably housed at the very back of the niche, directly between two of the boulders. In front of these two small rooms, a courtyard, possibly roofed, was created by enclosing the space with further brick walls (Kemp 1989:70, fig. 23). Although Predynastic pottery was found within the shrine, the small mudbrick buildings which formed the earliest shrine seem to date to the Early Dynastic period (Kemp 1989:69). During the first half of the First Dynasty, modifications to the adjacent fortress impinged directly upon the shrine, restricting the space in the forecourt. As a result, the entrance to the shrine had to be moved to the north. A subsequent strengthening of the fortified wall further reduced the area of the shrine forecourt. Indeed, the actions of the Early Dynastic state showed wilful disregard for local religious practices, and the community shrine was entirely neglected by the court in favour of a royal cult installation on the southern part of the island (Seidlmayer 1996b: 115). Towards the end of the Second Dynasty, the expansion of the town led to the abandonment of the inner fortifications. This allowed the shrine to expand once again, regaining its former extent. Further expansion of the sacred enclosure took place during the Third Dynasty and early Old Kingdom (Kaiser

et al.

1988:135–82; Ziermann 1993).

Figure 8.8

Early Dynastic shrines and temples. The map shows the sites at which Early Dynastic religious buildings are known to

have existed, based upon archaeological and/or inscriptional evidence. Capitals denote ancient place names.

A large collection of votive material was recovered from the floor of the shrine. Many of the pieces may be dated to the Early Dynastic period (Dreyer 1986:59–153; Kemp 1989:72, 73 fig. 24). Figurines of animals and humans in glazed composition form the most numerous group of objects. Animals represented include baboons, frogs and crocodiles. A particularly common type of votive offering consists of an oval-shaped faience plaque with the stylised head of a hedgehog at one end; 41 examples of this strange object have been recovered from the shrine. None of the objects gives an indication of the deity worshipped in the shrine. In later times, the sanctuary is known to have been dedicated to Satet, local goddess of Elephantine, but it is possible that the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods witnessed cultic practices of a more general nature. These may have focused in particular on the phenomenon of the annual inundation (Husson and Valbelle 1992:94) since, according to later beliefs, the waters of the inundation were believed to well up from a subterranean cavern beneath Elephantine.

Elkab

The temple at Elkab, presumably dedicated to the local goddess Nekhbet, received royal patronage at the end of the Second Dynasty, in the form of a stone building erected by Khasekhemwy. A carved granite block bearing the king’s name was found during excavations at the beginning of the twentieth century but was subsequently lost (Sayce and Clarke 1905:239). Two additional fragments showing human figures in low relief were found at the same time, but their present whereabouts are also unknown. Further, uninscribed granite blocks still standing in the same spot, just inside the northern corner of the Great Wall, confirm the location of the building (Hendrickx and Huyge 1989:13), in all probability a small shrine or temple.

The results of archaeological investigation in the main temple area indicate that a sacred building stood there from Early Dynastic times. On the site of the existing temple ruins, excavations failed to reveal any domestic settlement material later than the Early Dynastic period, suggesting that the site was demarcated as a sacred area prior to the Old Kingdom (Sayce and Clarke 1905:262). Being on a slight elevation, the temple site would have been prominent above the surrounding area (Sayce and Clarke 1905:262), and therefore ideally suited to a sacred role.

Hierakonpolis

The early twentieth-century excavators of Hierakonpolis found the remains of a circular mound in the centre of the large rectangular enclosure within the walled town of Nekhen (Quibell 1900:6, pl. IV; Quibell and Green 1902: pl. LXXII). A revetment of rough sandstone blocks enclosed a mound of clean desert sand. This structure has been dated to the Early Dynastic period (Hoffman 1980:131; Kemp 1989:75) and probably served as the foundation for a temple, which, like its predecessor on the low desert plain, is likely

to have been a reed-and-post shrine. The revetment itself probably symbolised the primeval mound, upon which, according to Egyptian mythology, the falcon Horus had first alighted. A pavement of compacted earth, reinforced by rough sandstone blocks in the areas of greatest wear, extended from the base of the mound on all sides, but especially to the south-east (Quibell and Green 1902:7). There were also the remains of rough limestone column bases or pedestals for statues, the exact function of which is not clear (Quibell and Green 1902:8; cf. B.Adams 1977). Excavations in 1969 confirmed that the stone revetment enclosing the mound of clean sand and the associated paved area date to the period of state formation. The remains of a door socket suggested that ‘access to the platform had been controlled by a gate or door’ (Hoffman 1980:131). Two parallel wall trenches and three post-holes indicated the existence of a building some 2 metres by

1.5 metres, either contemporary with the pavement or slightly earlier. It is tempting to identify the building as an early shrine made of posts and reed matting, perhaps even the

pr-wr,

the archetypal shrine of Upper Egypt (Hoffman 1980:132).

The temple of Horus was the location of the famous ‘Main Deposit’, a collection of votive objects probably buried some time in the New Kingdom: not only did the deposit lie immediately beneath an early New Kingdom temple, it even contained an Eighteenth Dynasty

scarab

and sherd (Kemp 1968:155). This makes accurate dating of uninscribed objects from the ‘Main Deposit’ extremely difficult (cf. B.Adams 1977). The most important early objects, the commemorative palettes and maceheads, bear witness to the patronage bestowed on the cult of Horus by the first kings of Egypt. The fact that kings like ‘Scorpion’ and Narmer dedicated such important artefacts in the temple emphasises the pre-eminence of the local god, Horus of Nekhen, as the deity intimately associated with divine kingship. Long after Hierakonpolis had lost its status as a centre of political importance, the presence of a temple to the supreme god of kingship ensured continued royal patronage: a number of stone elements with the name of Khasekhem(wy) probably derive from a temple or shrine, perhaps situated on the circular mound. One block shows a temple foundation scene (Engelbach 1934). The construction of houses during the Second and Third Dynasties apparently encroached upon the earlier temple, ‘leaving the mound rising above the new accumulation’ (Quibell and Green 1902:8).

Outside the rectangular enclosure, Green found a large limestone statue, much worn and damaged, but recognisably early in style and comparable to the colossi from Coptos (Quibell and Green 1902:15). The statue is cylindrical in form and represents a man wearing a long, off-the-shoulder cloak. The figure’s left arm is held horizontally across the chest, while the right arm, greatly elongated, hangs close to the side of the body. The right fist was perforated, perhaps to hold a mace or other object, as seems to have been the case with the Coptos colossi (Kemp 1989:81, fig. 28). The figure was evidently shown in the characteristic semi-striding position typical of later representations, with the left leg slightly advanced. The knees are crudely indicated, again a feature found in the Coptos colossi. An identification of the statue has not been established, but the piece clearly indicates the importance of the temple at Hierakonpolis at the very beginning of Egyptian history.

Other books

Ten Guilty Men (A DCI Morton Crime Novel Book 3) by Sean Campbell, Daniel Campbell

Lost Souls by Neil White

The Biggest Part of Me by Malinda Martin

Uschi! by Tony Ungawa

A Stranger in the Mirror by Sidney Sheldon

Dante's Marriage Pact by Day Leclaire

Skinny Dipping by Kaye, Alicia M

Thin Lives (Donati Bloodlines #3) by Bethany-Kris

Redefining Realness by Janet Mock

Revenge Wears Rubies by Bernard, Renee