Easter Island (23 page)

“I was beginning to wonder what a man had to do around here to get asked out.”

“Is that a yes?”

“I was running out of baked goods. I figured if I had to wait until spring, I could bring fresh fruit.”

“Yes, no. True, false. Are we going on a date, Professor Farraday?”

“All right. What are your plans for the holidays?”

“I was going to put in some extra lab time. With everybody gone I might actually get sunlight through a window.”

“No trips home?”

“No.”

“No family visits?”

“No family,” said Greer, hating how final this sounded. Her father had died just before she’d been accepted to graduate school, a blow that had knocked the wind out of her. School gave her something to occupy her mind, but she missed talking to him about classes, about lab, and she now wished she could talk to him about the man standing before her. Greer didn’t know what her father would think of her romantic life—her relationships in college hadn’t been significant enough to mention. Once, when she was home for the holidays, he had asked, “You have friends at school?” “Some,” she answered. “Special friends? Those can be as important as your studies.” “When I meet a man as interesting as botany, you’ll be the first to know,” she replied. After his death, she’d sold the house to finance her degree, and now there was no home she could go back to. Greer felt the weight of her admission hanging between her and Thomas. This was the first personal information they’d exchanged, the first hint that behind their late-night meetings, their banter and flirtation, lay real life, the past.

Thomas adjusted his mood accordingly. “Well, certainly you should have some plans for Christmas. That’s no day to be alone.”

“I didn’t exactly imagine

you

celebrating the birth of Christ.”

“I’m using the day to core on Lake Mendota.”

“Much better.”

“Would you like to come?”

“At last, a date.”

“A working date. If you do a good job, I’ll take you to dinner afterward.”

Greer considered this, letting her attention drift over the walls of his office: certificates, awards, more Latin calligraphy in this one room than she’d seen in a lifetime. She knew he liked her—he had, after all, pursued her—but it was still hard not to feel overwhelmed by who he was. She could think of only one way to shake her intimidation. “How about you take me to dinner Christmas Eve, and if you do a good job, I’ll consider helping you take samples the next day.”

“The next day?”

“We can arrange something,” said Greer. She scribbled her address on a sheet of paper and tore it from her notebook. “You have to hold the doorbell down hard,” she said. “If that doesn’t work, throw a snowball at the second-floor window.”

For the next two weeks they didn’t see each other. Greer heard from another student that Professor Farraday was lecturing at a symposium at the University of Iowa, and the shades on his office door were drawn. The campus buildings quieted, the crowds on State Street dissolved. Jo left to spend Christmas with Jeb and Jeremiah in Minneapolis, and for the first time, Greer, in her small apartment, looking at the rows of dark windows across the street, experienced the full realization of her solitude. When she was young she had gone on long horseback rides through the countryside by herself, watching birds or bullfrogs for hours on end—a kind of loneliness, but chosen. This was a sense of people vanishing, of empty rooms, and it unsettled her. She called Jo a few times but never reached her. She ate dinner out for the noise and the company. Mainly, Greer missed her father—it was her first winter without him, and even though she kept herself busy in the lab, working late into the night, shuffling endless slides beneath her microscope, it only reminded her how much she wanted to talk to him.

By Christmas Eve, her sadness had turned to numbness. Greer had simply tired herself with feeling lonely. She managed to put on a red cardigan Jo had told her looked good; she barretted her hair, rubbed some rouge on her face. But when he rang her doorbell, and she met him downstairs, her smile was strained.

“I should let you know I was entirely prepared to throw a snowball. Oh, no.” He was standing on the walkway. “I’m too late. The holiday blues have gotten hold of you.”

“I’m just tired,” said Greer, examining his face, recently shaven, and the sharp line of his jaw against the collar of his coat. She couldn’t believe he was there. And she couldn’t believe how much she had wanted to see him, what need she harbored in herself.

“Trust me, I know the look. It took me fifteen years to devise a way to avoid the holiday blues. And now, for the price of your charming company, I will share it with you. I’ll save you years of despair. Trust me.”

“

You

know the holiday blues?”

“Miss Sandor, I’ve spent most of my life alone. Holidays. Birthdays. Symposiums. Even football games. You are dealing with an expert in solitude. I’m an award-winning solitarian.”

There must have been women, thought Greer. Perhaps on other holidays, perhaps other students. But she had no desire to ask about that now. She was simply glad that he was here. Beneath his overcoat he wore a blue sweater over a plaid shirt—the shirt’s collar was crooked, one side tucked beneath the sweater’s neck, the other side flipped upside down, a plaid arrow at his chin. It was the first time she’d seen him in anything other than a suit. His cologne floated toward her on an icy breeze.

“But you’d rather not be alone,” she said.

“I’d rather you not be alone.”

“Well,” said Greer. “Ditto, then.”

They let a pleasant silence spread between them.

“Hungry?” he asked.

“Ravenous.”

“Good. Me too.” He linked his arm in hers and they stepped slowly down the icy path. “Button up,” he said. “It’s cold.”

“You too,” she said. They buttoned their coats, adjusted their scarves, watched their breath steam into the night. He then pulled up her collar and wrapped her scarf in one more loop around her neck. “There,” he said.

Greer suddenly felt happiness, in all its perfect confusion, rise like tears. She leaned forward and kissed him—a burst of heat in the cold. “Merry Christmas,” she said.

He smiled.

And she felt the numbness begin to slip from her. She felt it would be a good evening, that they would enjoy each other, that this—his arm threading itself through hers—was the period put on a sentence begun months earlier. They began to walk, and Greer looked at his face. There is great beauty in this man, she thought.

“All good?” he asked.

“Very good,” she said. He steadied her as they made their way slowly along the icy path. A cold wind battered their faces, and as they leaned into each other she felt the weight and the warmth of him all at once.

13

A

fter their ten-thousand-mile journey across the Pacific, after their eight-day rendezvous at Easter Island, the German squadron experienced a small victory at the Battle of Coronel.

On November 1, off the coast of Chile, Admiral von Spee detected the British

Glasgow

nearby. Von Spee, who had received reports of a single enemy cruiser in the area, ordered his fleet to overtake the ship.

The

Glasgow,

however, was part of Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s squadron, which lay nearby, unseen.

Admiral Cradock was equally misled. Reports had reached him of a single German cruiser,

Leipzig,

in the area, and by chance this was the first of von Spee’s ships he spotted. He, too, ordered his squadron into rapid combat against the single cruiser.

Each side believed it had the superior force, and by the time the situation was clear, action was under way.

The German ships carried more big-caliber guns and the weight of their fire was nearly double that of the British. Within two hours the Royal Navy lost two cruisers and nearly sixteen hundred men beside the Chilean town of Coronel.

Von Spee, from his lookout, was surveying the British cruisers, when suddenly flecks of red and green and yellow burst from one of the flaming ships, like bright scarves in the sky. They swirled in odd circles, then began to flutter—they were parrots. The British officers had released parrots bought in Brazil as gifts. The birds, however, were too stunned by the explosions to accept their freedom. Swooping about the smoky forecastle, they collided with the cannons; they perched on the gunwale as fires erupted around them. It was noted by a young German officer that almost one hundred birds soon bobbed lifelessly on the sea. “This seemed to all of us,” the young officer wrote in the last letter his mother would receive, “a most eerie omen.”

The Battle of Coronel was the first defeat suffered by the Royal Navy in over a century, and prompted First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill to send almost the entire British Fleet after von Spee. Churchill’s orders were unequivocal: “Your main and most important duty is to search for the German armored cruisers. . . . All other considerations are to be subordinated to this end.” Von Spee was in immense danger. The battle had expended nearly half his ships’ ammunition, depleting the only resources that might have saved his fleet and returned him home.

Also, the sinking of Admiral Cradock’s ship,

Good Hope,

contributed to von Spee’s growing tension. Von Spee had known Sir Christopher Cradock since his first posting to Tsingtao; he had sent a man with whom he’d been friends for fourteen years to the bottom of the sea.

Days later, at a dinner to celebrate their victory, an officer made a toast: “To the damnation of the British navy.” Von Spee then stood and raised his own glass, proclaiming: “I drink to the memory of a gallant and honorable foe!” Without waiting for support, he drained his glass, gathered his hat, and departed.

The portentousness of such a victory on November 1st would not have been lost on von Spee, a Catholic. It was All Saints’ Day.

—Fleet of Misfortune: Graf von Spee and the Impossible Journey Home

14

The island is honeycombed, a lattice of caves. In some distant past, these were homes, shelters, hideouts for women and children. Now they house only relics, scattered bones, and, according to legend, the spirit

tatane.

Two female

tatane

—Kava-ara and Kava-tua—are said to live in a cliffside cave on the northeast coast, keeping watch over the sleeping figure of the man they fell in love with centuries earlier and kidnapped from Hanga Roa. It is said that from the cliff’s edge you can hear the man gurgling in deep, silken sleep, and above that the singing of his

tatane

captors as they try—for if his spirit awakens it will take flight—to prolong his slumber.

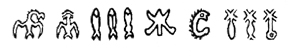

This is the only cave Biscuit Tin avoids. He knows them all, the caves strangled by grassy overgrowth, the caves clogged with lava rocks, the ones beneath the sharp cliffs splashed by surf, as though his short life has been spent exploring every inch of this island. Small and lithe, he can wiggle into the smallest of holes, emerging with a bone, a cracked clay pot, a wooden figurine, a salamander. He gives everything he retrieves to Alice, but she cares only for the strange tablet he presents one day: a three-foot-long piece of wood, oiled and worn, covered with pictorial engravings. As if reading braille, Alice runs her small hands across the mysterious script.

Alice then hands the tablet to Elsa. “Squiggles,” she says.

The moment Elsa touches it, she knows this is what she has been looking for. This is the script González noticed on his voyage almost one hundred and fifty years earlier, and deciphering it will be her project. The

moai

fascinate her, but their story belongs to Edward, and though she is glad to assist him, Elsa needs something of her own. She wants to secure a balance between them, even a distance. The tablet could record a genealogy, a legend, a codification of ancient law. It might help unravel the story of this island. If she can learn to read it, or grasp some small part of it, it will mean all her choices have served some higher purpose.

Her first task is to see if they can find more tablets. For weeks, led by Biscuit Tin, Elsa searches scores of caves, upturning skeletons, swatting at cobwebs, moving, one by one, the stones blocking secret chambers. Alice refuses to enter, so Edward waits with her outside while Elsa and Biscuit Tin survey the chambers. Edward has offered to go in, to let Elsa sit with Alice, but she has politely declined. If the tablets are her study, she should retrieve them. And, for practical purposes, she knows she is more agile than he is.

Soon they have amassed over twenty tablets and several inscribed staffs, the likes of which Elsa has never seen. The writing is an endless stream of small bulbous figures, hundreds squeezed onto each line. She has no immediate sense of whether the script is logographic, syllabic, or alphabetic. Some combinations of images appear over and over again, and some are unique. As she lays them side by side in the tent at night, the ambition of her task begins to overwhelm her. Where on earth does one begin to understand the markings? What she desperately needs is a key, her own Rosetta stone or Behistun rock, but the tablets seem filled with the hieroglyphics of one language alone.

She is thankful, now, for the distance from England, from scholars, from those qualified to take on this job. She knows it’s not the kind of project for a former governess, even the daughter of a professor. But she is here. And what, after all, is better than opportunity and desire?

First she decides to have Alice copy the figures, so they will at least have an accurate record. Also, Alice will be kept out of trouble.

For several weeks, Elsa sits on the hill above their campsite and reads Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson’s

A Commentary on the Cuneiform Inscriptions of Babylon and Assyria

and Champollion’s

Summary of the Hieroglyphic System of Ancient Egyptians.

Alice, beside her, sketches near-perfect reproductions of portions of each tablet.

As each series is completed, she shows Elsa. “Here, look.”