Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon Greatness (27 page)

Read Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon Greatness Online

Authors: Scott Jurek,Steve Friedman

Tags: #Diets, #Running & Jogging, #Health & Fitness, #Sports & Recreation

Most times, sunrise in the Italian Alps would cheer me. In August 2008, though, I was in third place in the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc, nursing a bloody knee.

Most times, sunrise in the Italian Alps would cheer me. In August 2008, though, I was in third place in the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc, nursing a bloody knee.

In 2010, New York Times columnist Mark Bittman interviewed me. Before any questions, he opened his fridge and asked me to prepare a meal. I whipped up a veggie and tofu stir-fry with homemade Indonesian almond sauce and quinoa.

In 2010, New York Times columnist Mark Bittman interviewed me. Before any questions, he opened his fridge and asked me to prepare a meal. I whipped up a veggie and tofu stir-fry with homemade Indonesian almond sauce and quinoa.

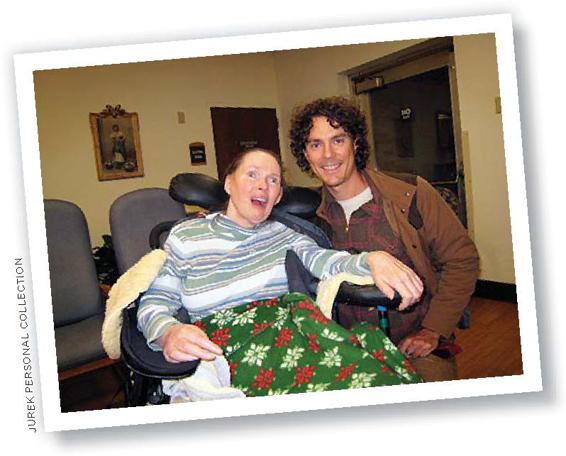

My mother struggled with Multiple Sclerosis most of her adult life, and her last few years were filled with pain. Her response to my concern was always the same and it still inspires me: "Don't worry about me. I'm tough."

My mother struggled with Multiple Sclerosis most of her adult life, and her last few years were filled with pain. Her response to my concern was always the same and it still inspires me: "Don't worry about me. I'm tough."

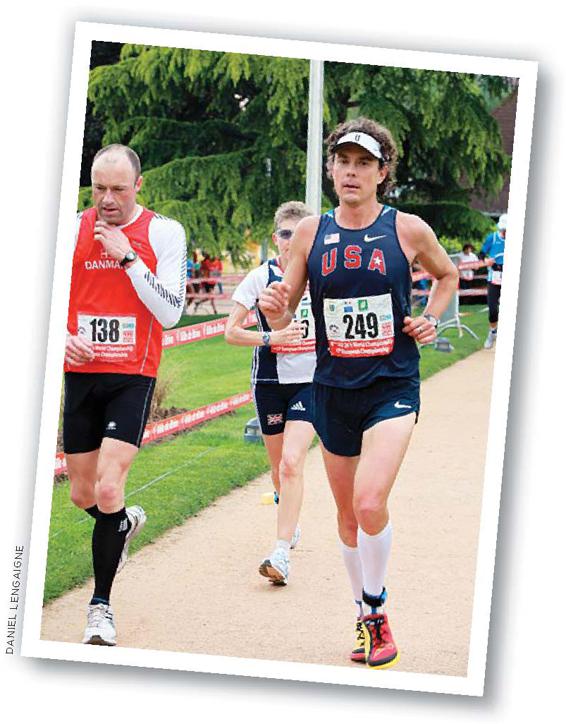

Mountains, deserts, and canyons bring with them fiendish challenges, but nothing compares to the monotony and mental strain of a 24-hour race. In 2010, I traveled to Brive la Gaillarde, France, to see if I could set a national record.

Mountains, deserts, and canyons bring with them fiendish challenges, but nothing compares to the monotony and mental strain of a 24-hour race. In 2010, I traveled to Brive la Gaillarde, France, to see if I could set a national record.

I met Jenny Uehisa in 2001 through the Seattle running community, and I was taken with her kindness, adventurous spirit, and infectious smile. Today, there's no one I depend upon more.

I met Jenny Uehisa in 2001 through the Seattle running community, and I was taken with her kindness, adventurous spirit, and infectious smile. Today, there's no one I depend upon more.

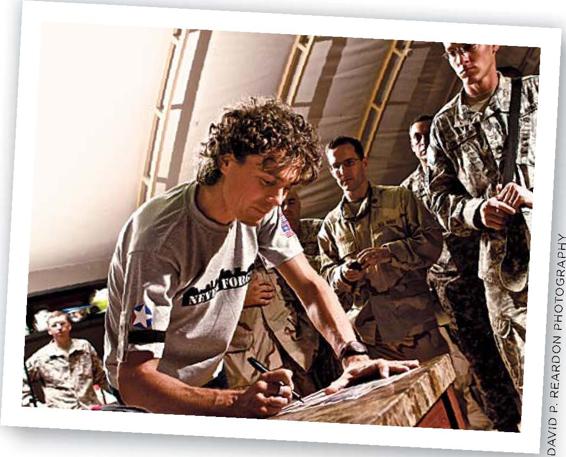

In September 2010, I went on a USO tour in Kuwait, where I ran alongside 1,400 soldiers in a 9/11 memorial event, signed autographs, and swapped stories. I consider the trip one of my greatest honors.

In September 2010, I went on a USO tour in Kuwait, where I ran alongside 1,400 soldiers in a 9/11 memorial event, signed autographs, and swapped stories. I consider the trip one of my greatest honors.

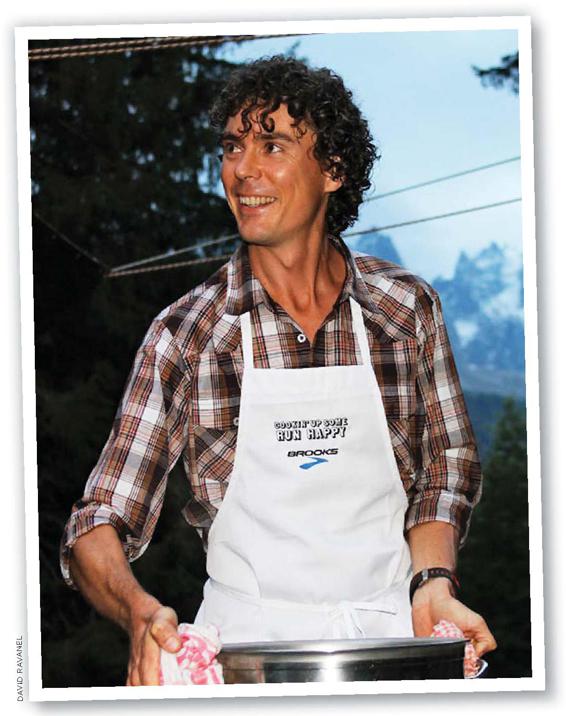

I love eating healthy food, but like my grandma Jurek, I find preparing it for others is almost as gratifying. In 2010, I cooked Thai curry and brown rice for fifty in Chamonix, France, a few days before the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc.

I love eating healthy food, but like my grandma Jurek, I find preparing it for others is almost as gratifying. In 2010, I cooked Thai curry and brown rice for fifty in Chamonix, France, a few days before the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc.

Popsicle sticks. I tried a stiffer insole. I told myself that I had almost nine days, that the body could do miraculous things.

Finally, I reminded myself to be grateful for my latest injury. It helped me remember why I ran ultras in the first place. It wasn’t for the chance to best a record. It wasn’t for simple physical pleasure. It was for something more profound, something deeper. To run 100 miles and more is to bring the body to the point of breaking, to bring the mind to the point of destruction, to arrive at that place where you can alter your consciousness. It was to see more clearly. As my yoga teacher would say, “Injuries are our best teachers.”

I’m convinced that a lot of people run ultramarathons for the same reason they take mood-altering drugs. I don’t mean to minimize the gifts of friendship, achievement, and closeness to nature that I’ve received in my running career. But the longer and farther I ran, the more I realized that what I was often chasing was a state of mind—a place where worries that seemed monumental melted away, where the beauty and timelessness of the universe, of the present moment, came into sharp focus. I don’t think anyone starts running distances to obtain that kind of vision. I certainly didn’t. But I don’t think anyone who runs ultra distances with regularity fails to get there. The trick is to recognize the vision when it comes over you. My broken toe helped me do that.

By the time of the race, my toe still hurt with every step, but I was trying to ignore the pain. I had other things to think about—Nunes, for example. Masayuki and Ryoichi from Japan, Austria’s Thalmann. The only other runner I paid some attention to was Polish, and he had run to Greece from his country, pushing a modified baby buggy that he had rigged to carry his goods and gear. Piotr Korylo had stopped in Rome to see the pope. I admired his single-mindedness, but figured he had to be exhausted. I didn’t see him as serious competition.

The Spartathlon course is hilly but not steep, which presents problems of its own. Even the fastest ultrarunners in the world are forced to walk steep sections of the Hardrock, for example, but in the Spartathlon the only excuse for walking is weakness. So I ran. Thalmann and Nunes went out first, as I expected. The Pole overtook Nunes after a mere 20K and was building a huge lead.

With no pacers, the first time you see your crew is 50 miles in. I kept a steady pace, occasionally downing some gels, potatoes, bananas, and energy drinks, willing myself to stay in the moment, to concentrate on the next step and the step after that. It was about five o’clock in the afternoon, the temperature was in the mid-90s, and I had climbed away from the sea, had woven in and out of orchards of orange trees and through the ancient, column-filled city of Corinth. I was running toward the sun, which was setting behind a great hill in front of me, turning everything a misty, thick red. I tried to not think too much; in a race this long, at a moment this hot, with lips this parched, thinking could be dangerous. It too easily led to a calm, rational assessment of where I was, how far I had to go. Rational assessments too often led to rational surrenders. I tried to go to that place beyond thinking, that place that can bring an ultramarathoner such happiness.

People always ask me what I think about when running so far for so many hours. Random thinking is the enemy of the ultramarathoner. Thinking is best used for the primitive essentials: when I ate last, the distance to the next aid station, the location of the competition, my pace. Other than those considerations, the key is to become immersed in the present moment where nothing else matters.

But I was struggling to hold on to third place, and I was

so

thirsty. Every time I saw someone—a villager, a vintner, an old lady sitting in a patch of shade—I yelled, “

Paghos nero parakalo,

” which means “ice and water, please,” but no one seemed to understand. Finally, emerging from a chalky, lonely taverna, a bent old woman in a long, navy blue dress shuffled toward me. “

Paghos nero parakalo,

” I called, and miraculously she seemed to understand. She yelled something to a man standing in the doorway as she mimed drinking.

She had thick arms, thick ankles, and a rough, weather-beaten face. Her husband handed her a large glass of water filled with chunks of ice, and she gave it to me. The ice could have come from keeping freshly caught fish cold. I could not have cared less. To me, the chunks were more valuable than glittering diamonds. She also picked a handful of basil leaves from the garden at her feet and thrust them into my hands. I was trying to drink and thank her at the same time when I saw her motioning to the basil leaves and then to my small waistpack, where I carried my gels and food. She was telling me to put the basil in there. When I took the pack off, though, she pulled one of the leaves out and stuck it behind my ear. Then she kissed me on the cheek.

Suddenly I felt a lightness and a strength. Whether it was her kindness, the water, or the basil (which I discovered later is the king of herbs, the word

basil

deriving from the Greek word

basileus,

which means

king

; it is revered as a symbol of strength and good luck in Greece), my mind shifted. It was the moment in an ultramarathon that I have learned to live for, to love. It was that time when everything seems hopeless, when to go on seems futile, and when a small act of kindness, another step, a sip of water, can make you realize that

nothing

is futile, that going on—especially when going on seems so foolish—is the most meaningful thing in the world. Many runners have encountered that type of crystalline vision at the end of a race, or training run, that brings with it utter fatigue and blessed exhaustion. For ultrarunners, the vision is a given.