Eat Him If You Like (2 page)

Read Eat Him If You Like Online

Authors: Jean Teulé

Alain was hailed on all sides as villagers jostled each other to let him through. The crowd divided, forming a semicircle. Seen from the sky, it looked like a smile. He entered and the human mouth closed behind him.

‘The whole place is teeming!’

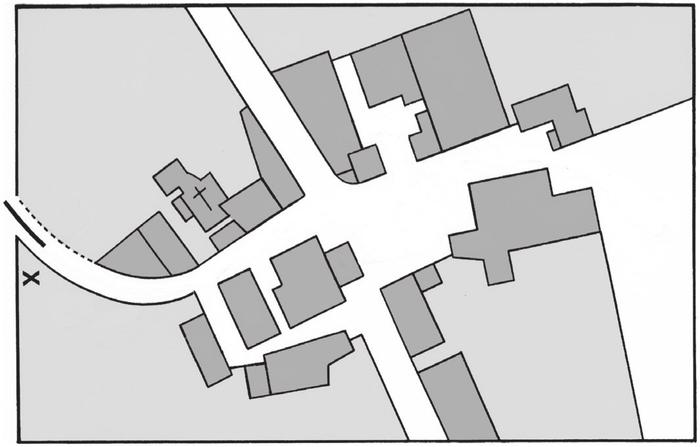

On his left, he could see the triangular garden between the priest’s house and the church. The adjacent meadow had been transformed into a pig and donkey market for the day. He headed in that direction. The fair had not extended to the meadows on the right because they were blocked off by a low dry-stone wall.

People continued to flock up to Hautefaye from the surrounding countryside. They were dressed in their Sunday best – flat caps, smocks, clogs and ribbons. Each held a stick or cattle prod to chivvy along their livestock. Alain watched them wind their way in columns up to the top of the hill where the village sat, with it’s magnificent view.

‘What a lot of people have come for the Saint-Roch fair this year! Don’t you agree, Antoine Léchelle?’

‘Oh, good day, Monsieur de Monéys. Yes, I’ve never seen such a crowd. Twice as many people as usual. Six or seven hundred, they say, which is surprising in a village of just forty-five souls. The crowds stretch right to the other side of the village and the fair goes down to the dried-up lake.’

‘I wouldn’t be surprised if all the inhabitants of all the surrounding hamlets had decided to gather here today. Probably everyone within a fifteen-mile radius has turned up. How are you, Antoine?’

‘Things were better when we had some water,’ replied Antoine Léchelle, a wicker basket at his feet. ‘Feuillade hasn’t seen a drop these last eight months. The crops have all withered. They’ve shrivelled up in the heat wave. Our cattle are dying.’ The worried villager toyed idly with his hat. ‘Some people say it’s a comet. I do hope it won’t land on our heads! The barometer’s still rising.’

Behind him, a couple of young calves struggled to keep their balance.

‘You don’t seem to have any females there, Antoine. I’m looking for a heifer for our Bertille.’

‘They’re with the other cows over there by the dried-up lake.’

‘And how’s business?’

‘Bad. We just can’t find any cattle dealers prepared to take the animals off our hands. I’ve never known anything like it. Everything is going wrong this year and the hens are barely laying either.’

‘Put your eggs in the shade, Antoine. They’ll bake in the sun.’

‘Silly me! What’s the matter with me today?’

Alain continued on his way, trying to beat a path through the horseflies that buzzed relentlessly around the livestock. He was surrounded by the stench of animals, the shouts of horse dealers and the low drone of conversation. From time to time he would overhear the odd snippet: ‘This heat! Soon we’ll be trying to get water from stones!’ ‘My throat’s as dry as kindling. I’m almost afraid that if I spit, I’ll start a fire!’ A little old man who sold umbrellas was complaining he hadn’t sold enough this year. He was speaking to Sarlat, a tailor from Nontronneau. Sarlat peered through his glasses at Alain as he passed, recognised the summer suit that he himself had made, gave Alain a thumbs up, winking to let him know that it looked good on him. The smell of frying meat and doughnuts hung in the air, but hardly anyone could afford to buy them. Someone was telling a story:

‘So, the prefect of Ribérac went up to the mayor here in Hautefaye and asked, “Do you have any rebels in your region?” To which the mayor replied, “We’ve got brown bulls and black bulls, but no re-bulls!”’

‘That Bernard Mathieu, he does come out with them. I don’t know where he gets them from! He says such funny things,’ chuckled a cobbler.

Despite the laughter around him, Alain had the impression that, this year, the place was pretending to be jolly. Sweating men tanned from the sun spread lard and rubbed garlic on their crusts of bread, which they swallowed down, rolling their worried eyes as they ate. On the other side of the road, Alain spotted the ragman he had overtaken on his horse earlier and to whom he had promised his ‘scraps’. The man was sitting on the low dry-stone wall looking stricken.

‘What’s wrong with him this year?’

‘Piarrouty learnt of his son’s death yesterday,’ explained a nearby man. ‘He was shot in the head by a machine gun at Reichshoffen. A letter was sent to the mayor’s house in Lussas. It was from one of the boy’s injured friends who’d found him shot to smithereens. He’d even picked a lucky number, but a pharmacist’s son who had an unlucky one bought it from him at Pons.’

The old ragman remained prostrate, his weighing hook across his thighs and a bottle of wine at his feet. He was distraught that he had sold his son to replace someone else. A loud droning sound came from the crowd. Small knots of people started to form. The heat was becoming heavy and oppressive.

Alain shook hands with the friendly villagers as he passed. Small landowners like himself, at the fair to do business, wandered amongst the crowd. The opulent glint of rings on their fingers made them easy to identify. They stopped to talk to tenant farmers about breaking the terms of their lease, and said they would discuss the matter again on St Michael’s day, when it was the tradition for bosses and workers to settle their yearly accounts.

‘Oh, Alain,’ said Pierre Antony, a friend and neighbour, as he approached, ‘I wanted to congratulate you on being elected unanimously as leader of Beaussac town council! There never was a worthier candidate.’

‘Amédée must be so proud!’ added a stonemason from Beaussac, referring to Alain’s father. Then he asked, ‘What’s this plan of yours to divert the Nizonne that everyone’s talking about?’

‘Well, Jean Frédérique, it’s a question of changing the river’s course slightly. At the moment, a lot of water runs into the fields and is wasted. Uncultivated land will be transformed into pastureland and our insalubrious countryside will become hospitable and prosperous. People will benefit from these works for hundreds of years to come. I finished my report this morning and I shall send it to the government shortly.’

‘Well, if you manage to convince those men in the ministry, then it won’t be a waste of ink,’ said Jean Frédérique, clasping Alain’s hands warmly.

‘You should stand for election to Parliament!’ exclaimed Antony admiringly, flattering Alain.

‘Oh, it is quite enough to be deputy mayor of Beaussac. My political ambition stops there,’ he replied. He then asked the stonemason if he had spotted the carpenter from Fayemarteau in the crowd.

‘Brut? I saw him earlier at one of the inns, but I can’t remember whether it was Élie Mondout’s or Mousnier’s place.’

Alain glanced in the direction of the two inns in the centre of the village. They were packed. Men clustered around the

tables and bottles were being passed around. There were so many people at the inns that Anna Mondout – the beautiful young girl who wanted to learn to read and write – was also bringing carafes of wine to the fair’s entrance. She went over and served the horse traders, who were leaning against the priest’s garden wall. They clinked their glasses, which flashed in the light.

‘To the Emperor! To victory! To the destruction of Prussia and the death of Bismarck! If he ever dares to come to Hautefaye, we’ll give him something to remember us by!’

Anna moved on to the labourers, gelders and wheelwrights, and filled their glasses with the nectar.

‘Is this rainwater you’re bringing us?’

‘It’s Noah, a white wine from Rossignol.’

‘Blow me, that’s strong!’ said the men, tasting it and giving their verdict.

They paid their three sous, but thought that the wine was rather expensive. Anna – a sweet, pale girl with dark eyes and long eyelashes, wearing a grey and green dress – went on her way. Her straw hat blew off and her hair glinted red in the sun. Nearby, a pedlar was trying to sell a bundle of newspapers that had just arrived from Nontron. Even those who only knew how to read a few basic words in large print were snapping them up and trying to decipher the front page of the

Dordogne Echo

. Some of them were holding the paper upside down.

‘I don’t have my glasses. Can somebody read what it says?’

A broad-shouldered man in a black frock-coat read aloud the front-page headline above the five columns that

Alain had not wanted to read to his mother. ‘

DEFEAT AT FROESCHWILLER, REICHSHOFFEN, WOERTH AND FORBACH

,’ he announced, and then summed up the article below and gave his opinion. ‘Things aren’t going as well as hoped for the French armies at the border. The Emperor is done for. They’re out of ammunition.’

Alain recognised the arrogant voice. It belonged to his cousin, Camille de Maillard.

‘This pointless war, supposedly “fresh and joyous”, is turning into a disaster,’ he continued. ‘Yet the Minister for War promised that “we are ready, more than ready. This will be a Sunday stroll from Paris to Berlin.” Well, that’s news to me, because Reichshoffen was a massacre.’

Piarrouty rose from his perch on the low, stone wall and turned to face the crowd. Around Alain’s cousin, the news hit like a punch in the stomach.

‘That’s not true!’ cried someone in protest. ‘That’s impossible! You don’t know what’s going on. To say that our emperor, who beat the Austrians in Italy and the Russians in the Crimea, isn’t capable of holding back a few Prussians. Come now …’

‘Our army has had to retreat to the Moselle!’ responded de Maillard. ‘It says so in the newspaper.’

Silence descended on the villagers who had gathered around de Maillard, the bearer of bad news. Many of them stared at their feet or gazed into the distance. The labourer from Javerlhac was sad that his glass was already empty and that he couldn’t afford to refill it.

‘You’re an idiot,’ he said.

‘You’re no more able to read than we are,’ said a sawyer

from Vieux-Mareuil, examining a large fly crawling on his finger.

‘The French will never retreat!’ shouted a butcher from Charras, flicking the fly away as it came to land on his nose.

But de Maillard was emphatic. By saying that he knew for certain that the most recent battles had been even bloodier than reported in the

Dordogne Echo

, he was spreading panic amongst the relatives of soldiers. He said the government had ordered that the real numbers of dead be hushed up in case people started to worry. He said the war was lost, that Napoleon III was beaten and that perhaps nothing could stop the Prussians from taking over France. ‘Regrettably,’ he said, wincing, but nobody heard his sigh.

His pessimistic analysis of the situation caused indignation. A donkey brayed. Pigs banged their snouts against the fences. Two men in leather aprons carrying goads chivvied along a calf. The tinsmiths started to bang on their cauldrons with mallets. Horse traders, whips slung over their shoulders, moved closer, their voices growing louder. The strong wine was already going to people’s heads.

‘It’s awful to hear such things. To think that some people are happy about what’s happening!’ grumbled a villager under his breath, fiddling with his shirt-tails and not daring to look up.

‘Long live the militia!’ shouted somebody, already tipsy on cheap wine.

Camille de Maillard’s servant, Jean-Jean, who was standing nearby, must have sensed danger. Failed businesses,

drought and now fear of invasion were poisoning the fair’s atmosphere. He whispered urgently into his master’s ear. As de Maillard turned his head sideways, Alain could not fail to recognise his sideburns, cut in the style of old King Louis-Philippe. Suddenly, the arrogant young man bolted, pushing people out of his way, and jumping over the low wall to the right of the road with Jean-Jean at his heels. They ran across the sloping field and headed for a small wood. Three villagers jumped the barrier as well and followed them. It was almost like a children’s game, like watching little tin soldiers on a green baize surface. The farmers soon fell behind, their boots hampering their progress. De Maillard and his servant fled as quickly as they could. People seemed furious that they had managed to escape. Their pursuers returned, climbed back over the low, stone wall and surveyed the crowd.

‘Now now, my friends, what’s going on?’ said Alain, limping towards them.

‘It’s your cousin,’ explained a pedlar. ‘He shouted, “Long live Prussia!”’

‘What? No! Come now, I was standing just here, and that’s not what I heard at all! And I know de Maillard well enough to be sure that he would never say such a thing. “Long live Prussia”? That’s almost as ridiculous as shouting “Down with France!”’

‘What did you just say?’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘You said “Down with France!”’

‘What? No, of course I didn’t!’

‘Yes, you did! You said “Down with France!”’

‘But no, I didn’t say that. I—’

‘All those who heard him cry “Down with France!” raise your hand!’ said the pedlar, addressing the people standing by the low wall.

‘Oh, I heard him say “Down with France!”’ said a voice, and a hand shot up.

Other fists were raised, five, then ten. Some villagers who may not even have heard the question saw hands go up and raised theirs too. People asked their neighbours what had happened.