Eden's Outcasts (54 page)

Authors: John Matteson

Is not your paradise an Inferno? Please never name itâ¦. Would you destroy my paradise, too? Come with me, come, and I will show you Elysium; I know all about it, I am not deceived. I feel it to be solid, safe. It makes good its pledges always. I have a home of all delights,â¦while you seem [a vagabond]â¦bereft of friendsâ¦. Am I to quit my present satisfactions for your promised joys? Unkind! this taking me from my paradise, unless you conduct me to a happier?

48

Bronson had once thought he had known better than anyone else the true nature of a worldly Elysium. He now quietly conceded that, in a child's play garden, there were greater worlds than had been dreamt of in his and Charles Lane's philosophy.

Like the work of fiction that was simultaneously absorbing the efforts of his daughter,

Tablets

pays homage to domestic life and celebrates the home as the wellspring of virtue. But whereas

Little Women

is about the change from childhood to maturity and takes the individual life as its measuring unit,

Tablets

emphasizes the aspects of human existence that remain essentially unchanged across generations. Bronson's metaphorical means for transcending time was the idea of the garden, a place that connected him not only with the earth but also with distant ages. In his discourse on the garden, which takes up more than one fourth of the total length of

Tablets

, Alcott makes the obvious association between the modern garden and Eden, but he also cites Homer, Xenophon, Virgil, Columella, and the Bhagavad Gita. If the literary associations are grand, Alcott's applications of them emphasize humility. A garden, he writes, “may be the smallest conceivable, a flower bed only, yet it is prized none the less for that. It is loved all the more for its smallness, and the better cared for.”

49

Even the physical appearance of Bronson's book, which Louisa called “very simple outside, wise and beautiful within,” reinforced his message of simplicity.

50

To grow and eat one's own food was, for Bronson, to commune with an otherwise lost Arcadian past. In his efforts to raise the garden to a revered condition of nobility, Bronson occasionally stumbled into historic triviality and Orphic silliness, as when he reported that “the Emperor Tiberius held parsnips in high repute,” and when he proclaimed, “Lettuce has always been loyal.”

51

Nevertheless, Bronson's tribute to the garden is a convincing document. In

Tablets

, the soil becomes an aid to virtue, a spur to reflection, and a passport to serenity. “A people's freshest literature,” he wrote, “springs from free soil, tilled by free men. Every man owes primary duty to the soil, and shall be held incapable by coming generations, if he neglect planting an orchard at least, if not a family, or book for their benefit.”

52

Like Voltaire's Candide, Alcott finds refuge and redemption in work; his garden is not an Edenic place of ease, but a place where elemental tasks, earnestly undertaken, “promote us from things to persons.”

53

Removing the worker from the realms of anxiety and caprice, work, as Alcott ideally perceives it, “revenges on fortune, and so keeps us by

THE ONE

amidst the multitude of our perplexitiesâagainst reverses, and above want.”

54

Perhaps Alcott's most effusive words are reserved for women, in whom he observes a keenness of insight denied to men: “Entering the school of sensibility with life, she seizes personal qualities by a subtlety of logic over-leaping all deductions of the slower reason; her divinations touching the quick of things as if herself were personally part of the chemistry of life itself.”

55

To men seeking advice regarding womankind, Alcott urges that they should offer two things that women were too often denied: respectful treatment and the ballot box. No republic could call itself great, he insisted, while it excluded women from public life. He cautioned, “Certainly liberty is in danger of running into license while woman is excluded from exercising political as well as social restraint upon its excesses. Nor is the state planted securely till she possess equal privileges with men in forming its laws and takingâ¦part in their administration.”

56

One of the first great works of transcendentalism, Emerson's

Nature

, begins with the complaint “Our age is retrospective.”

57

The second half of

Tablets

, one of the last great transcendental texts, begins with the rallying cry “Our time is revolutionary.”

58

In Alcott's estimation, the American Age was to be an age of glory.

While its commercial success did not approach that of

Little Women, Tablets

promptly went into a second edition.

59

It also garnered enthusiastic reviews. Of these, none was sweeter than the assessment of the

Chicago Tribune

: “Mr. Emerson has been to Mr. Alcott as Plato to Socrates. He has elaborated where the elder thinker did little but meditate and converse. He has written for the world what his senior contemporary has wrought out in his closet. Alcott was an Emersonian Transcendentalist before Emerson.”

60

Bronson himself would never have claimed a superior relation to Emerson, who, he admitted, “has no peer with his pen.”

61

Nevertheless, the perception that the two were in the same class must have gratified him greatly.

Although

Tablets

discourses broadly and abstractly on the nature of women, family, and friends, it contains no anecdotes or personalities.

Little Women

is also a search for truth and love and the meaning of life, but it follows the path not of philosophy but of memory. Not seeking a high, smooth road to perfection, it began with the idea that goodness was not a status but a struggle. It did not take its freshness from the soil but from the struggles of people who try, fail, and forgive. Now, more than a century later,

Little Women

remains available everywhere;

Tablets

, by contrast, is out of print and long forgotten. To those with access to the latter volume, however, it is a rare treat to read the two works side by side, as two complementary glimpses into the past, and into the heart of the Alcott family.

“THE WISE AND BEAUTIFUL TRUTHS OF THE FATHER”

“Under every privation, every wrong, and with the keen sense of injustice present, the dear family were sustained.”

â

A. BRONSON ALCOTT,

Journals,

June 10â14, 1878

I

N HIS JOURNAL, BRONSON KEPT CLOSER TRACK OF LOUISA'S SALES

figures than his own.

1

He spent part of an early September day in 1869 reading over the notices of

Little Women.

He had a fine collection of them, assembled from all over the country and from every major city. The general verdict placed his daughter in the first rank of writers of fiction. Bronson received this judgment with happy disbelief. He felt even deeper pride, however, in Louisa's modest reaction to it all. She received her accolades as if there had been some strange mistake that was sure to be corrected soon. Louisa judged herself unworthy. The public emphatically disagreed, and for once, Bronson was more than happy to side against his daughter.

Bronson paused to consider how Louisa's success fitted into his own life, a life filled with fitful seeking after grand achievements and equally full of disappointments. No child who had sat in his classroom or at his table had ever acted in a public fashion to carry on the work of conscience and creativity Bronson had begun. None, that is, until Louisa, the one who had once seemed least of all to embody or even to understand his spirit and principles. So often the victim of ironic circumstance, Bronson could justifiably glory in this turn of fate. He had long ago surmised that the family was the best of all models for a school. Now, he observed with satisfaction that his family had yielded his truest scholars:

I, indeed, have great reason to rejoice in my children, finding in them so many of their mother's excellencies, and have especially to thank the Friend of families and Giver of good wives that I was led to her acquaintance and fellowship when life and a future opened before me.

2

Bronson then wrote the most accurate assessment of his and Abba's lives that he ever committed to paper: “Our children are our best worksâif indeed we may claim them as ours, save in the nurture we bestowed on them.”

3

For those hungry for a happy ending, the story of Bronson and Louisa May Alcott might comfortably end here. The goals that had danced so enticingly but inaccessibly before Louisa's eyes when she was a growing girlâfame, wealth, and the admiration of her fatherâwere all securely hers. Bronson, having finally written a successful book and having acquired the enduring sobriquet “the Father of Little Women,” had earned the assurance of an eager and interested audience. Almost simultaneously, and with each other's assistance, father and daughter had arrived at an apex in their lives.

Yet Louisa could not thoroughly enjoy her hard-won happiness. Since childhood she had heard in her mind the voice of incessant want. Just as her father had become used to finding contentment in what he had, Louisa had become habituated to desire. If happiness means the fulfillment of all one's wishes, then Louisa was fated never to know happiness, for she never ran out of wishes. She was by no means a greedy or selfish person; indeed, her wishes for others far outnumbered and routinely took precedence over her own quiet longings. Nevertheless, her characteristic state of mind had in it a sense of constant insufficiency that she seemed powerless to eradicate.

Then, too, there was the continuing problem of her health. Finishing

Little Women

had exhausted her. Once accustomed to working fourteen hours a day, she now had days when she could not write at all. Even in April, more than three months after sending the second half of

Little Women

to Roberts Brothers, she still felt “quite used up.”

4

Still not suspecting that her ill health stemmed from a less treatable cause than overwork, she wanted only to rest and recover, but her suddenly adoring public clamored for her. Louisa was initially charmed by the letters she received from admiring children.

5

Before long, however, she became astonished by the forwardness with which fans and journalists alike presumed upon her time and patience. She wrote in her journal, “People begin to come and stare at the Alcotts. Reporters haunt the place to look at the authoress, who dodges into the woods

à la

Hawthorne, and won't be even a very small lion.”

6

People were coming to Concord in droves, and not just to peer at Louisa and her family. A great many Americans were feeling an urge to recover some portion of the tranquility that the Civil War and its aftermath had stolen from them. To some of them, the town of Concord, with its gentle, tree-lined roads and its reputation for detached contemplation, spoke irresistibly. In its own day, transcendentalism may have struck these visitors as strange and quixotic. Now that its apostles were gray or departed, the revelations of the Over-soul seemed no longer a threatening disruption to the status quo but a welcome refuge from it. As a result, Louisa complained, “No spot is safe, no hour sacred, and fame is beginning to be considered an expensive luxury by the Concordians.”

7

For much of the year, Louisa was able to evade the questing throngs by removing to Boston. Sharing quarters with her sister May, she spent the winter of 1868â69 in the city, first in a new hotel on Beacon Street and later at a boardinghouse at 53 Chauncy Street. But when spring and Louisa both returned to Orchard House, she was again annoyed by the intrusions of the philosophy-struck and the curious who had mistaken her for an exhibit.

In early May, resurrecting her alter ego of Tribulation Periwinkle from

Hospital Sketches

, she sent a letter of withering satire to the

Springfield Republican

, in which she deftly lampooned the modern-day pilgrims. She reported in jest that a new hotel called “The Sphinx's Head” was soon to welcome the transcendental tourists, who would be served “Walden water, aesthetic tea, and wine that never grew within the belly of the grape.” After dining on wild apples and Orphic acorns and warming themselves by the sacred fires, fed from the Emersonian woodpile, devotees would be issued telescopes with which to view “the soarings of the Oversoul.” She also imagined a daily program of events for the entertainment of the faithful, for instance: “Emerson will walk at 4 p.mâ¦. Channing may be seen with the naked eye at sunset. The new Hermit will grind his meal at noon, precisely.” Among the rest, Louisa could not resist a jibe at her inexhaustibly garrulous father. Her bulletin also advertised: “Alcott will converse from 8 a.m. till 11 p.m.”

8

Louisa imagined what fun it would be to repel inquisitive strangers with a garden hose. It was ever clearer to her that she needed to escape.

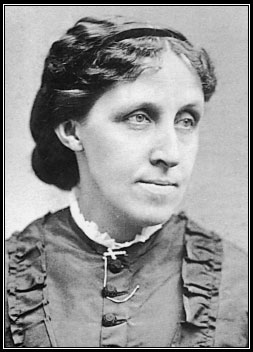

Louisa May Alcott at the height of her popularity.

(Courtesy of the Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Her initial retreats from the Boston area were relatively modest. She passed a quiet midsummer month with her cousins the Frothinghams at their house in Quebec. Mount Desert Island, off the coast of Maine, also became a refuge, and she spent August there with May. Meanwhile, the stream of revenue from

Little Women

flowed on. She entrusted the money that remained after paying the family's debts to her financially savvy cousin Samuel Sewall. Upon sending him the first two hundred dollars, she had exulted, “What richness to have a little not needed!”

9

Her growing nest egg was, she admitted, enabling her to bear her neuralgia more cheerfully.

Bronson could not help crowing over Louisa's financial success. He boasted to Frank Sanborn at the beginning of September that twenty-three thousand copies of

Little Women

had been printed and added that

Hospital Sketches

, now reissued with eight other stories under the title

Hospital Sketches and Camp and Fireside Stories

, was also enjoying a revival. He was eager for her to begin the novel about his life that she had first conceived a dozen years earlier, “The Cost of an Idea.” Bronson felt that this book would be “a taking piece of family biography, as attractive as any fiction and having the merit of being purely American.”

10

The Americanness of Louisa's work mattered greatly to Bronson. Not only did he maintain that she was among the first to draw her work from the life, scenes, and character of New England, but she had absorbed less foreign sentiment than any other writer he knew. If in other ways Bronson fretted over Louisa's lack of formal education, he felt her writing style was one aspect in which the absence of too much academic influence had served her well. It was, he thought, her “freedom from the trammels of school and sects” that gave her work its irresistible frankness and truth.

11

At the end of August, Louisa returned from Maine, improved in spirits though not in physical vigor. Bronson hoped that she might begin writing “The Cost of an Idea” immediately. He proposed taking her to Spindle Hill, which she had not seen since childhood, so that she might begin her research. However, Louisa's health required a series of postponements. In mid-October, Bronson observed that she was still far from well.

12

Louisa was also eager for a return trip to Europe, but this too would have to wait. In the meantime, Louisa found it more prudent to work on a book that would require no field research, but would draw instead on the readier resources of her own experience and imagination. She may also have sensed that her readers might prefer a story of another virtuous young heroine to the quixotic flounderings of a misunderstood philosopher. In October, she took another room in Boston with May. Paying little heed to her chronic pain, she descended into another writing vortex. Her imagination was captured by the image of an innocent but morally sturdy young girl who stands firm against the materialistic frivolities that seduce her more worldly and citified friends. She called the new book

An Old-Fashioned Girl

.

Like Dickens, Stowe, and others before her, Louisa had learned the trick of selling the same story twice: first as a magazine serial and then as a hard-bound book. Initially serialized in monthly installments in

Merry's Museum

throughout the second half of 1869,

An Old-Fashioned Girl

did not appear in book form until April 1870. Although the response from both readers and critics was generally enthusiastic, the reviewer for

The Atlantic Monthly

was not alone in complaining that the book contained some bad grammar and even some poor writing. In response to such criticism, Louisa told her family, “If people knew how O.F.G. was written, in what a hurry and pain and woe, they would wonder that there was any grammar at all.”

13

Louisa tended to discuss her work in disparaging terms, and her ready dismissal of

An Old-Fashioned Girl

therefore comes as no surprise. Nevertheless, the book ranks among the best of Alcott's children's fiction. Unlike many of her novels for juveniles, which are really little more than a series of sketches and vignettes,

An Old-Fashioned Girl

is confidently plotted and steadily develops its central theme: the shallowness of fashionable living and its particularly destructive effect on young women, whom it renders physically weak, emotionally vacant, and morally aimless. Alcott's cautionary tale trains much of its focus on the Shaw family, who, but for the beneficent influence of an ethically upright outsider, would doubtless have tumbled into ruin. Mrs. Shaw, an otherwise inoffensive woman, is a model citizen of Alcott's modern-day Vanity Fair. Her three children, also essentially good-natured but lacking any useful guidance, seek lives of ease, popularity, and pleasure. Fourteen-year-old Tom is forming the neglectful habits that will later plunge him into debt and expel him from college. His sister Fanny divides her time between reading cheap novels and buying costly hats. Even six-year-old Maud proves a quick study of her elders' vanities; she is already adroit at aping the fashionable nerves and sick headaches of her mother. The only moral ballast within the household is supplied by Mr. Shaw and his seventy-year-old mother. However, the latter is too old to have her counsels regarded, and the former has become too enmeshed in the pursuit of wealth to assert any real authority.

Salvation arrives in the person of Fanny's friend Polly Milton. Coming from the countryside to pay a lengthy visit to the Shaws, Polly is initially scandalized by their worldly manners. Fortunately, she refrains from openly rebuking her hosts, and over time and despite innumerable setbacks, the Shaw children learn from her the merits of selflessness and the evils of vanity. Mrs. Shaw proves something of a lost cause. When, however, Mr. Shaw's business fails, all three of his children rally around him, having finally understood Polly's example of sincere caring and faithful industry.

The more interesting problem for Alcott the author is not how Polly is to reform the Shaws, but how to tell so didactic a story without having it dissolve into a cloying, condescending sermon.

An Old-Fashioned Girl

escapes this fate in large part because Polly avoids the unctuousness that might be expected of her. Her goodness is neither self-righteous nor self-congratulating; it flows from an unaffected nature and a simple belief that kindness creates more happiness than self-indulgence. The real strength of Alcott's tale, however, derives from the book's firm advocacy of women's rights, supported by its conviction that sexual equality is not the cause of a political faction but a tenet of common sense. In demonstrating Polly's superiority over the Fanny Shaws of the world, Alcott protests a social system that fosters a commercialized sense of human value, a system particularly degrading to women. Allowed to participate in the marketplace only as purchasers, Fanny and her friends are themselves reduced to ornamental commodities. By resisting to define herself in objectifying economic terms, Polly tacitly insists that to live is not to have, but to think, to feel, and to do.