Edge (13 page)

Authors: M. E. Kerr

I was mad! You bet I was mad!

But I worked on the ceiling, even while I was cursing my father. I was careful, too, neatnik that I am, I'd covered everything around me so paint wouldn't get on it.

I put newspapers down to keep the stove and the icebox clean.

I was about to do the last wall when I went out in the yard to shake my father and tell him he had to wake up and help! It was

his

idea to do them this favor, not mine!

The thing was, I'd never thought about that old gas stove. We had an electric stove, and so did everyone I knew.

While I was out yelling at Dad, the pilot light on the stove must have worked through the newspapers.

“I'm not going to paint anymore until you get up!” I told Dad.

“Who said you had to paint?” He had one eye open.

“You called me for help, remember?”

“I changed my mind.” He turned over in the hammock, his back to me.

The fire must have been running along the walls just as I sat down in the beach chair and said, “Have it your way, Dad.”

I don't know if he heard me.

But soon we both heard the whoooosh and then the roar of the fire as it hit the propane gas tanks.

I can't stand to drive down Bay Street and see the lick of land where Far and Away used to be.

Robert and Paul are long gone from this town now, but in my mind's eye, I still see their shocked, sad faces as we stood out on the lawn that sunny afternoon, the smell of burnt wood in the air, what was left of the house black and smoking.

Everyone, including them, still believe my father set that fire somehow, even though I figured out how it started, and later an inspector from the fire department confirmed it.

There are certain truths no one wants to hear. No one can believe truths that are hard to accept, either.

For example, who would ever believe that the real reason Far and Away burned down was that my father was trying to do a favor for Robert and Paul?

A Personal History by M. E. Kerr

M

y real name is Marijane Meaker.

When I first came to New York City from the University of Missouri, I wanted to be a writer. To be a writer back then, one needed to have an agent. I sent stories out to a long list of agents, but no one wanted to represent me. So, I decided to buy some expensive stationery and become my own agent. All of my clients were me with made-up names and backgrounds. “Vin Packer” was a male writer of mystery and suspense. “Edgar and Mamie Stone” were an elderly couple from Maine who wrote confession stories. (They lived far away, so editors would not invite them for lunch.) “Laura Winston” wrote short stories for magazines like

Ladies' Home Journal

. “Mary James” wrote only for Scholastic. Her bestseller is

Shoebag

, a book about a cockroach who turns into a little boy.

My most successful writer was Vin Packer. I wrote twenty-one paperback suspense novels as Packer. When I wanted to take credit for these books, my editor told me I could not, because Vin Packer was the bestselling authorânot Marijane Meaker.

I was friends with Louise Fitzhughâauthor of

Harriet the Spy

âwho lived near me in New York City. We often took time away from our writing to have lunch, and we would gripe about writing being such hard work. Louise would claim that writing suspense novels was easier than writing for children because you could rob and murder and include other “fun things.” I'd answer that children's writing seemed much easier; describing adults from a kid's eye, writing about school and siblingsâthere was endless material.

I asked Louise what children's book she would recommend, and she said I'd probably like Paul Zindel's

The Pigman

, a book for children slightly older than her audience. I did like it, a lot, and I decided my next book would be a teenage one (at the time, we didn't use the term “YA” to describe that genre). I knew I would need yet another pseudonym for this venture, so I invented one, a take-off on my last name, Meaker: M. E. Kerr. (Louise, on the other hand, never tried to write for adults. She was

a very good artist, and her internal quarrel was whether to be a writer or a painter.)

Dinky Hocker Shoots Smack!

was my first Kerr novel. The story of an overweight and sassy fifteen-year-old girl from Brooklyn, New York,

Dinky

was an immediate success. Between 1972 and 2009, thirty-six editions were published in five languages.

Gentlehands

, a novel as successful as

Dinky

but without the humor, is a romance between a small-town boy and a rich, sophisticated Hamptons summer girl. The nickname of the boy's grandfather is Gentlehands, but he is anything but gentle. An escaped Holocaust concentration camp guard, he once took pleasure in torturing the female prisoners. His American family does not know about his past until the authorities track him down. Harrowing as the story is, the

New York Times

called it “important and useful as an introduction to the grotesque character of the Nazi period.”

One of the hardest books for me to write was

Little Little

, my book about dwarfs. I kept worrying that I wouldn't get my little heroine's voice right. How would someone like that feel, a child so unlike others? After a while, I finally realized we had a lot in common. As a gay youngster, with no one I knew who was gay, I had no peers, no one like me to befriendâjust like my teenage dwarf. She finally goes to a meeting of little people and finds friends, just as years later I finally met others like me in New York City.

I also used my experience being gay in a Kerr novel called

Deliver Us from Evie

. I set the story in Missouri, where I had studied journalism at the state university. I had been a tomboy, so I made my lead character, Evie, a butch lesbian. She is skillful at farm chores few females would be interested in, dresses boyishly, and has little interest in the one neighborhood boy who is attracted to her. I didn't want to feminize her to make her more acceptable, and I worried a bit that she would be too much for the critics. Fortunately, my readers liked Evie and her younger brother, Parr, who doesn't want to take over the family farm when he grows up. The book is now in two thousand libraries worldwide.

When I write for kids, I often draw on experiences I had when I was a teenager living in Auburn, New Yorkâa prison city. All of us were fascinated by the large stone building in the center of town, with gun-carrying guards walking around its stone wall. Called Cayuga Prison (Auburn is in Cayuga County), it appears in several of my books. One of these books is called

Your Eyes in Stars

.

Growing up, I was friends with a boy whose family was in the funeral business. As the only male, he was expected to take over the business when he grew up. Can you imagine looking forward to that in your future? Neither could Jack, who inspired

I'll Love You When You're More Like Me

.

My book

Night Kites

is about AIDS. To my knowledge, it was the first print book that featured two gay men who have contracted AIDS, rather than having the illness come about because of a blood transfusion. When we first learned of AIDS in 1981, everyone grew afraid of old friends who were gay males. There was a cruel joke that “gay” stood for “got AIDS yet?” But soon we realized AIDS was not just a gay problem. The book is set in the Hamptons, though much of the action takes place on a Missouri farm.

I have also written a teenage autobiography, called

Me Me Me Me M

e, which deals with my years growing up in upstate New York during the thirties and forties. My older brother, Ellis, was a fighter pilot in the naval air force, seeing action over Japan. After World War II, he fought in Vietnam for our secret airline Air America, and later in Korea. He was my favorite relative until Vietnam. We had a major falling-out over the war when he called me a “peacenik.” We never felt the same about each other after that, up until his death in the nineties. My much younger brother has lived with his family most of his life in Arizona. We don't see as much of each other as we'd like because of the distance between our homes.

I have always given my parents credit for my becoming a writer. My father was a great reader. Our living room was filled with walls of books. I grew up with him reading to me, and ultimately began reading any novel he did. But I am a writer largely due to my mom's love of gossip. Our venetian blinds were always at a tilt in our house because Mother watched the neighbors day and night. Many of her telephone conversations began, “Wait till you hear this!” On execution nights in our prison, my mother and her girlfriends huddled outside in a car, waiting for the executioner to go inside. He was one of ten men who entered the prison together on execution night, so no one snooping could know who had really pulled the switch.

I have taught writing for thirty-four years at nearby Ashawagh Hall in East Hampton, where I've lived most of my adult life. We benefit, in part, the Springs Scholarship Fund. My teaching inspired me to write

Blood on the Forehead: What I Know about Writing

. A dozen members who had never finished a book became published writers after joining the class, and we also have members who are already professional writers. Currently, I am in the middle of a memoir called

Remind Me

. The title comes from an old Mabel Mercer song:

Remind me not to find you so attractive

Remind me that the world is full of men

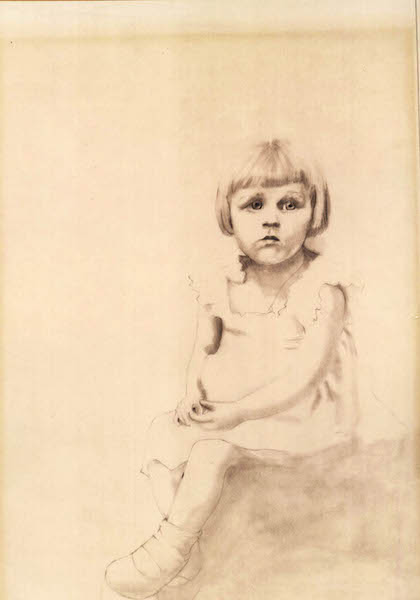

Portrait of Meaker, drawn by Louise Fitzhugh from a baby picture.

Seven-year-old Meaker, her mother, and her brother Ellis in Auburn, New York.

Meaker (front left) with her mother, her brother Ellis, her father, and several other Meakers at the home of British relatives in Brighton in 1938.

Meaker as a girl scout in Auburn in 1939.

Meaker, age seventeen, with her first car, a 1937 LaSalle convertible with a rumble seat, and a sailor from Sampson Naval Base. The bane of her parents' existencesâboth the base and the sailors.