Edge of the Orison (10 page)

Read Edge of the Orison Online

Authors: Iain Sinclair

And what of Clare's mysterious poem, ‘A Moment's Rapture While Bearing the Lovely Weight of A.S’?

Now lovely Anna in her Sunday dress

In softest pressure sits upon my knee

This young woman, whoever she was, gives her name to Clare's first child, born in 1820.

Anna belonged to Glinton in a way that her mother, a Lancastrian, never did. The awkwardness for Joan Hadman, her first visit after marriage, of those farmers' meals, quantities she couldn't manage, green bacon with ruffs of heavy fat. The slithery weight of it, food too close to source, pigs in the orchard; the decorative pattern on the plate buried under layers of freshly killed meat. ‘She's pleasant,’ her mother-in-law reported, ‘but unfinished.’

We never hear what Mary Joyce, the tenant farmer's daughter, thought of John Clare. It's always his side of the story, the walnut thrown in the schoolyard, the walks to North Fen bridge, yards of poetry (attempts to trap her in a mythic past). There is no written account of Mary's time in that Lady Chapel school, her afterlife, post Clare. Young woman, social being. Spinster living at home. It's a harsh destiny: muse by appointment. Heritage pests paying their respects at the wrong grave.

Anna locked her cousin Virginia (Gini) in the empty pig sheds and left her there. She remembers where the sheds were, on the far side of the lane. Ground that is built over, new houses. Discovered, she was imprisoned in that concrete box as a suitable punishment.

On later visits to Glinton, Anna was putting on time, slightly melancholy (as it might appear), but generally content, waiting for something: an operation, entrance to university. Auntie Mary to the rescue. Inflamed appendix. Taken out of school. Three weeks in hospital. Then, as the rest of the family went on holiday, Anna

was left behind. The operation would be performed in September, when her parents returned. Meanwhile, a warm, dusty August, forbidden to swim, she hung about with her aunt. She did swim (permission granted by local doctor) in the gravel pits, deep cold, clear water: out at Tallington, beyond Lolham Bridges, where Clare cut his initials into stone, and where he fished.

Before Dublin, her start at Trinity College (where, at last, our paths cross), Anna was back at Glinton. An August like one of those French novels told in letters, solitary bicycle rides through flat country, heat haze, lazy rivers. Law books piled up, unread, beside a deckchair: seasonal lethargy. She'd been working as a receptionist at a hotel in Blackpool, the big one, the Imperial; catching the eye (tall, dark, dramatic) of businessmen and French waiters, but still living at home. This was a different movie. English rite of passage at the seaside (social surrealism), Blackpool always obliging to location scouts. Her father walked into the Imperial with a party of colleagues and pretended to flirt. He made her write a poem a day, every day, no nonsense about inspiration, a poetry notebook. The Clare inheritance (with chasers of Rupert Brooke): approved subjects in established forms. Prize-winning sonnets.

Myron Nutting's 1923 sketch of Lucia Anna Joyce (daughter of notorious Paris-domiciled novelist, James) replicates Anna Had-man's Glinton interlude. Weight of hair, tilted head, eyes closed in concentration, pen in hand: the duty of composition. Winning paternal approval. Task set, with good intentions, by a troubled father: be what you are, my daughter. Demonstrate the gifts I gave you. Geoffrey Hadman made family sketches. He worked in pencil, chalk, crayon; portraits of his children, of the gardener, craggy work folk. Portraits of Anna. Sitting, as ordered, unoccupied; inventing herself, slowly.

We followed the North Fen path Clare is supposed to have taken with Mary Joyce, out towards the trysting bridge. It was a walk Anna often took with her aunt and the golden Labradors. Balcony House had long since been sold, the garden pebbled and planted in

a Jacobean style that played up to the unusual balcony addition. The weather was kind; our path soon escaped the village. But it was not the path Anna remembered. The high, wild hedges were gone, fields were exposed. This landscape, evidently, had come full cycle: the hedges and odd-shaped strips of enclosure returned to the wide horizons of Clare's childhood. William Hadman, before moving to the Red House, had his farm out here: ground once occupied by James Joyce, Mary's father. William rented his property to the eccentric Mrs Benson, who ran it as a home for children, which she later moved to another gloomy property in Rectory Lane.

Thorny copses offer good cover as we approach the bridge and its heritage prompts. A humped silver car squeezes past and is later discovered, parked on the verge, dos-à-dos to a muddy hatchback. (Number plates blanked to protect the guilty.)

I notice a bush that has been dressed, country fashion, with a limp crop of grapeskin condoms. Over a mulch of crumpled cigarette packets. Pie wrappings. Discarded tights.

Beyond Car Dyke and the Welland, the half-hidden Paradise Lane leads straight to Northborough and the poet's cottage; which is now in the keeping, so we discover, of a dealer in teddy bears. Northborough is heavy with absence; of all the cemetery villages encountered on our walk out of Essex, this is the paradigm. Internal exile as a prelude to the Big Sleep.

We confront the bridge. Three bands of human affection can be felt: the romance of those youthful lovers, John Clare and Mary Joyce, given emphasis by our demand that it should be so, innocence before the fall; then illicit conjugations, off-road couplings authorised by the signboard broadcasting Clare's passion; and, finally, a stolen time with Anna, triggering memories of all our earlier walks. Embraces. Collusion. Private interludes rescued from domestic routine. The knowledge that you may be watched is both exciting and inhibiting: in a landscape shaped for ambiguity. Assignations, close talk in parked cars. A line of furled poplars diminishing into a blue distance.

I draw from Anna an account of her Glinton holidays, village

school, appendix operation, forbidden swim – and, most vividly, that period before we met, before she came to Dublin, the afternoons cycling down these lanes, sitting on the lawn, in her bedroom with the window open: a compulsion, lightly held, to remake the past, mend a fractured narrative.

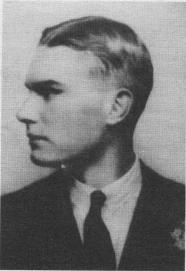

Her father had friends in Germany, student years, late Twenties, early Thirties, everybody went there. Auden, Isherwood, Spender. University men, gays. Left and right, all persuasions. Samuel Beckett. The friendship with his cousin, Peggy Sinclair. Geoffrey Hadman, returned from Oxford, poses against a tall hedge in the garden of the Red House. ‘What a handsome man,’ my daughter said. Blazer and flannels, heavy brows, off-centre parting, frowning at the camera: clenched left hand. A moment of consequence. Excellent degree (1932). Newspaper cuttings of his performance in the ‘half-mile handicap’. Scrapbook thick with young women, rivers, parties, snow. Big coats, arrogant hats. The women are laughing. The men are pleased.

GLINTON SCHOLAR'S SUCCESS

Mr. Geoffrey Hadman, youngest son of Mr. and Mrs. Had-man, of the Red House, Glinton, has gained first-class honours and his B.Sc. degree at Oxford University.

Mr. Hadman is an Old Boy of Stamford School, to which he won a scholarship from Glinton School at the age of 10. Whilst at Stamford he became head boy and captain of the Rugby Team. He was also prominent in running and swimming, winning many honours in both…

After spending a well-earned holiday with his parents, in September Mr. Hadman takes up a post with Imperial Chemical Industries.

Among Anna's files is a letter from Imperial Chemical Industries to the headmaster of Stamford School.

Subject to the fulfilment of these conditions, the commencing salary to be not less than £350 per annum. If Hadman should prove satisfactory he would be continued in our employment and would be given an agreement for a period of years, with every prospect of advancement

.

Might I ask you to be good enough to communicate this decision to the boy

…

Anna bribed £10 to cram five hundred words of German vocabulary (never used). That climate of cultural seriousness combined with physical exercise, nude bathing, mountain walks (Leni Riefenstahl): a firm grip on social problems, the mob. Students in college scarves driving buses and ambulances at the time of the General Strike. Now it was spoilt, Germany. Painfully so. Friendships suspended.

From Oxford, the best of times, into digs in Thornton Cleveleys, north of Blackpool. According to family legend, Geoffrey Hadman

was the youngest works' manager ever appointed by ICI, that global power. Mercurial, he challenged received notions: premature

free marketeer. He was elected as a Conservative (for want of a stronger word) to the local council, but couldn't stick the addlebrained bureaucracy. Lancastrian committee men brokering deals on a nod and a wink. Debate not decision.

There was to be no advance within the corporate structure. No invitation to join the main board. An early ceiling. Too bright, too singular: too bloody-minded. Team captain, not team player: action in place of consensus politics and spin.

He brooded on radio news: Germany and England, the breaking of that bond. The splitting of the atom: Anna remembers her father, alone in a darkened room, knowing immediately what the announcement meant. ‘It's the end.’ The children talked in whispers. Her mother stayed out of the way. Anna was the one deputed to sit with him, keeping him company.

Something happened. Something that is hard to appreciate: a brain tumour, one son says. An episode nobody but a man as driven as Geoffrey Hadman would interpret as a sign of weakness. Anna thinks it was more probably a stroke, requiring weeks, months, in hospital. Out of circulation. ‘We thought you were dead,’ colleagues muttered when he reappeared.

Geoffrey didn't tell his parents. He wrote letters from his hospital bed without alluding to the drama. He let them think he was still at work. He ignored, as far as was possible, the partial paralysis in his left side, the clawed hand. He couldn't run, but he would walk, shoot, load the children into the Bedford van on cold Lancashire evenings, wind cutting off the Irish Sea, a compulsory dip in the murky waters. Poppa would set out from the house in a towelling robe, driving barefoot, stiff leg on pedal.

‘I am a new man,’ John Clare wrote to his Cambridge friend, Chauncy Hare Townsend, ‘and have too many tongues.’ The Helpston boy divorced himself from ‘the old silence of rusticity’. For every social gain, there was private loss. He knew that he was no longer the subject of his own story. Succeed elsewhere and you can't go home again.

When Anna was flown across England, Blackpool to Glinton,

her father had suffered his stroke; loss of sensitivity in the left side, dragging leg. His fingers wouldn't open. In a car, he drove at speed, impatient with socialist regulations. Now, high over fields and roads and reservoirs, atrophied nerves tightened the grip on the joystick. The young girl in the bucket seat was unafraid.

DREAMING

Anxiety – ghosts, nothing specific.

Max Brod (on Kafka)

Poet in the Park

He had to learn the difficult thing, in different places we are different people. We live in one envelope with a multitude of voices, lulling them by regular habits, of rising, labouring, eating, taking pleasure and exercise: other selves, in suspension, slumber but remain wakeful. Walking confirms identity. We are never more than an extension of the ground on which we live.

The birds knew him, knew John Clare, a wanderer in fields and woods; they recognised him and he belonged. They proved his right to common air. He shared their heat. Twenty-three years fixed in Helpston, between limestone outcrop and Fen, flailing, herding, stalking the circle, minor expeditions, runs at the horizon. The child lost among the yellow furze of Emmonsales Heath. The crabbed adolescent on the barge, Peterborough to Wisbech. The hot young man tramping to Newark. The lime-burner landing himself with a wife. On an invisible leash, Clare was drawn back, always, to his ‘hut’, hovel, home.

Poetry is a form of going away. Of holding landscape, and its overwhelming, simultaneous particulars, in the float of memory. ‘For Clare, as for all poets in the Romantic tradition,’ wrote Jonathan Bate, ‘writing was the place of remembering, of preserving what was lost: childhood, first love, moments of vision, glimpses of ordinary things made extraordinary by virtue of the attention bestowed upon them. Without loss, there would be no reason for the poetry.’

It arrived, this seizure, disturbing intimations of destiny, as Clare walked back from the market town of Stamford, towards Barnack and his cottage at Helpston. The first Clare biographer, Frederick W. Martin, publishing in the year after the poet's death, turns the documented materials of a life into romantic fiction; a fiction

extracted from Clare's scribblings, his papers. Extracted from a single visit to Helpston, interrogation of unreliable witnesses. Everything folds back into Clare's own telling, his autobiographical ‘sketches’. Freed from punctuation, memory flows, racing ahead of itself in accordance with the (future) Kerouacian recipe for spontaneous composition: first thought, best thought.