Eight Little Piggies (17 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

The hinges in the wings of an earwig, and the joints of its antennae, are as highly wrought, as if the Creator had nothing else to finish. We see no signs of diminution of care by multiplicity of objects, or of distraction of thought by variety. We have no reason to fear, therefore, our being forgotten, or overlooked, or neglected.

I can offer only two responses—both, I think, powerful and quite conducive to joyous optimism, if this be your fortunate temperament. We may lose a great deal of easy, unthinking, superficial comfort in the rejection of Paley’s God. But think what we gain in toughness, in respect for nature by knowledge of our limited place, in appreciation for human uniqueness by recognition that moral inquiry is our struggle, not nature’s display. Think also what we gain in increments of real knowledge—and what could be more precious—by knowing that evolution has patterned the history of life and shaped our own origin.

Thomas Henry Huxley faced the same dilemma more than one hundred years ago. Chided by his theologian buddy Charles Kingsley for abandoning the traditional solace of religion in Paley’s style, Huxley replied:

Had I lived a couple of centuries earlier I could have fancied a devil scoffing at me…and asking me what profit it was to have stripped myself of the hopes and consolations of the mass of mankind? To which my only reply was and is—Oh devil! truth is better than much profit.

And a gain of such magnitude is no barleycorn.

SOMETIME

, in a better world to come, the wolf shall dwell with the lamb on Isaiah’s holy mountain. Once, in the better world that was, Leonardo painted exquisite women, Michelangelo rendered the hand of God, and Raphael captured the even greater age of Plato and Aristotle in the

School of Athens

. (I know that these gentlemen have recently mutated into Teenage Ninja Turtles, and so perhaps may we measure the direction of changing excellence in history.)

The myth of a past golden age seems irresistible, but the contrary reality is undeniable. Leonardo built some frightening instruments of war; Michelangelo struggled against the virulent homophobia of his generation; and Raphael died on his thirty-seventh birthday.

A persistent and cardinal legend of this mythology holds that the age of Michelangelo encouraged people of talent to range across all realms of mind and art, to follow that wondrously optimistic motto of Francis Bacon: “I have taken all knowledge for my province.” In our present age of narrow specialization, we continue to credit this reverie by referring to a broad-ranging scholar as a “Renaissance man.”

But suspicion, deprecation, and narrowness have a pedigree as old as enlightenment. Professionals have always tried to seal the borders of their trade, and to snipe at any outsider with a pretense to amateur enthusiasm (though amateurs who truly love their subject, as the etymology of their status proclaims, often acquire far more expertise than the average time-clock-punching breadwinner). The classic maxim of narrowness—“a cobbler should stick to his last”—dates from the fourth century

B.C.

, the great age of Athens. (A “last,” by the way, is a shoemaker’s model foot, not an abstract claim about perseverance.)

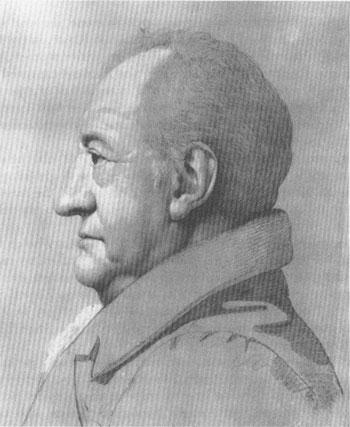

Sketch of Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1817).

Courtesy of Nationale Forchungs- und Gedenkstallen der klassischen deutschen Literatur in Weimar

.

Nothing—not even acknowledged greatness—can secure a clear passport for distant intellectual migration. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who enjoyed the ultimate pleasure of general regard in his own time as the world’s greatest poet, complained bitterly of his reception by scientists for considerable labor in their domain (Goethe did serious work, often with great success, in anatomy, botany, geology, and optics). Near the end of his life, in 1831, Goethe wrote:

The public was taken aback, for…it is expected that a person who has distinguished himself in one field, whose manner and style are generally recognized and esteemed, will not leave his field, much less venture into one entirely unrelated. Should an individual attempt this, no gratitude is shown him; indeed, even when he does his task well, he is given no special praise.

Goethe’s spirited defense against this parochialism not only displays his own justifiably expansive ego, but also asserts an intellectual’s most precious birthright.

But a man of lively intellect feels that he exists not for the public’s sake, but for his own. He does not care to tire himself out and wear himself down by doing the same thing over and over again. Moreover, every energetic man of talent has something universal in him, causing him to cast about here and there and to select his field of activity according to his own desire.

Six years after Goethe’s death, in 1838, the French biologist Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire devoted an entire article to justifying Goethe’s scientific excursions:

Sur les travaux zoologiques et anatomiques de Goethe

. (On the zoological and anatomical work of Goethe). (In his very last article, Goethe had defended Isidore’s more famous father Etienne Geoffroy in his celebrated confrontation with Georges Cuvier on theories of anatomy, so Isidore’s article might be viewed as the repayment of a debt, one generation removed.) Isidore gave incisive expression to the parochial tendencies of scientists:

Many well-informed people still do not know whether Goethe was limited to propagating ideas already developed in science by reclothing them in the colors of his admirable style, or whether he can claim the greater glory of an originator. Naturalists themselves hesitate to recognize as one of their own a man whom they have been accustomed, for so long, to admire as a dramatic poet, a novelist, and even as a writer of songs…. The more that this distance [between art and science] be viewed as immense, perhaps even unbridgeable, the more we have difficulty in imagining that the same hand that wrote Werther and Faust…could hold the anatomical scalpel with skill—and the more we may view this accomplished prodigy as admirable because he was able to combine intellectual qualities that ordinarily exclude each other.

Not that Goethe (or his reputation) needs my defense, but I do devote this essay to fighting the professional narrowness that Isidore Geoffroy identified and deplored—a tendency that has intensified with a vengeance in the 150 years since Isidore’s article, for we modern scholars often treat our professions as fortresses and our spokespeople as archers on the parapets, searching the landscape for any incursion from an alien field.

We might mount two kinds of defense for generosity towards incursion from scholars in other fields (beyond the general principle of virtue in ecumenicism and variety). The weaker claim—I shall call it universalism—holds that all good thinkers operate in pretty much the same way, and that benefits offered by outsiders are largely quantitative. Intellectual progress is tough, and we need all the help we can get, so why bar access to brilliant people in other disciplines? Although I will offer a different defense for Goethe, universalism is often a good argument. For example, I would not struggle against sexism (as many scientists have) by claiming that women tend to reason in a different but equally valuable way. I regard such a claim as both false and demeaning. We need to open all fields to women because it is simply absurd, given the rarity of genius, to recruit from only half the potential pool.

The second and stronger claim—I shall call it

special insight

—holds that we should value outsiders not simply as more bodies, but as potentially applying to their extracurricular concerns a fresh and different mode of thinking imported from their central profession. (I call this claim stronger because narrow professionals might accept the argument of more bodies, but usually rebel against special insight with the rallying cry of all parochialisms—how dare they come into my garden and tell me how to cultivate my tomatoes!)

In the case of Goethe and science, I advance this second claim of special insight for two reasons. First, I feel that characteristic ways of thinking in the arts—the role of the imagination, holistic vs. reductionistic approaches, for example—might enlighten science (not because scientists never think in this “artful” manner, but because the unpopularity of these styles among professionals greatly limits their fruitful use, and an infusion from outside might therefore help). Second, Goethe himself viewed his treatment of biological problems as different from that of most full-time scientists, and he attributed his unconventional approach to his training and practice in the arts.

In particular, Goethe argued that his artist’s perspective led him to view nature as a unity, to search for integration among disparate parts, to find some law of inherent concord. Goethe wrote:

What is all intercourse with nature if by the analytic method we merely occupy ourselves with individual material parts, and do not feel the breath of the spirit, which prescribes every part its direction, and orders, or sanctions, every deviation, by means of an inherent law!

I may then pose the cardinal question of this essay: Did Goethe get any mileage for his unconventional “artist’s” approach in science? Did it work? The answer, I think, is undoubtedly “yes.” We might hold that Goethe’s general brilliance allowed him to succeed whatever cockamamie method he happened to use—and that his artist’s vision of integration and imagination didn’t really help after all. But we might also take him at his word, admit the efficacy of his approach, and try to appreciate the message of pluralism and the artificiality of conventional boundaries among disciplines.

Goethe had a taste of success early in his career, in 1784, when he discovered a new bone in the human upper jaw. He called this bone the

intermaxillary

; others dubbed it

Goethe’s bone

. He insisted that such a bone must exist in humans (prior to any evidence and in the face of general denial) because other terrestrial vertebrates possessed it—and such a bone must therefore belong to the archetype, or abstract generating plan, of all reptiles, birds, and mammals. (This bone is called the premaxillary in other vertebrates; it generally holds the upper incisor teeth in mammals.) In humans, the small intermaxillary fuses with other bones of the upper jaw and cannot be recognized in skeletons after birth; Goethe ascertained its existence by noting the sutures that form before fusion in embryos. In an essay written in 1832, the year of his death, Goethe recalled this discovery as “the first battle and the first triumph of my youth.” He attributed his success to his artist’s vision of necessary unity: The bone must exist in humans if all terrestrial vertebrates share a common and abstract plan of development.

Goethe published his most important biological work in 1790—

Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären

(An attempt to explain the metamorphosis of plants). This work, a pamphlet devoid of illustrations or charts and consisting of 123 numbered, largely aphoristic passages, can scarcely be called a document of conventional science. It embodies the two principles that Goethe attributed to his artistic predilections—bold hypotheses based on assumptions of inherent unity. And yet, though Goethe’s central notion cannot be sustained, this curious little work is full of insight and has exerted a strong influence over the history of morphology (a word coined by Goethe). We may accept the assessment of Goethe’s scientific champion Etienne Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire, written in 1831:

The professional knowledge of the naturalist—what one might call the mechanical part—appears nowhere; no descriptions of flowers are given; no experiments are noted. It is the book of a scientist for its fund of ideas but, in its format, it is the book of a philosopher who expresses himself as a poet. Nonetheless, we must accept it as an excellent treatise in natural history.

Most subtle arguments can be ridiculed by oversimplification and stereotype. Goethe’s theory of plant form has been particularly subject to such unfair treatment because his drive to find unifying themes did lead him to a bold hypothesis, all too easily caricatured. Goethe worked within a developing morphological tradition generally called

unity of type

. He longed to find an archetype—an abstract generating form—to which all the parts of plants might be related as diversified products.

Many of Goethe’s colleagues sought the archetype of animal skeletons in the vertebra. (Etienne Geoffroy tried to homologize the external carapace of arthropods with the internal skeleton of vertebrates, and to identify the abstract vertebra as archetype of both. He actually claimed that insects therefore lived within their own vertebrae, and that insect legs represented the same structure as vertebrate ribs.) Goethe, following the same approach in another kingdom, held that the archetypal form for all plant parts—from cotyledons, to stem leaves, to sepals, petals, pistils, stamens, and fruit—could be found in the leaf.

The caricature of Goethe’s theory therefore proclaims “all plant parts are leaves” (with the implied corollary, “ha, ha, ha, what nonsense”). But Goethe said no such thing. First of all, the archetype is not an actual maple leaf or pine needle, but an abstract generating form, from which stem leaves depart least in actual expression. Goethe defended his use of the common word

leaf

in describing his archetypal idea:

We ought to have a general term with which to designate this diversely metamorphosed organ and with which to compare all manifestations of its form…We might equally well say that a stamen is a contracted petal, as that a petal is a stamen in a state of expansion; or that a sepal is a contracted stem leaf approaching a certain state of refinement, as that a stem leaf is an expanded sepal.

Secondly, Goethe’s theory applies only to the lateral and terminal organs of ordinary plants, not to the supporting roots and stems. Goethe’s defensive reaction to criticism on this point does not rank among his best arguments, but I cannot fault him for omitting stems and roots; after all, a theory for all appended parts is no mean thing, even if the underlying superstructure goes unaddressed. Goethe says that he copped out because roots are such lowly objects!

My critics have taken me to task for not considering the root in my treatment of plant metamorphosis…. I was not concerned with it at all, for what had I to do with an organ which takes the form of strings, ropes, bulbs and knots…, an organ where endless varieties make their appearance and where none advances. And it is advance solely that could attract me, hold me, and sweep me along on my course.