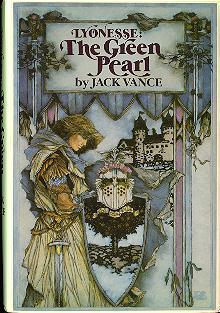

Elder Isles 2: The Green Pearl

Read Elder Isles 2: The Green Pearl Online

Authors: Jack Vance

The Green Pearl

by Jack Vance

VISBHUME,apprentice to the recently dead Hippolito, applied to the sorcerer Tamurello for a similar post, but was denied. Visbhume then offered for sale a box containing articles which he had carried away from Hippolito’s house. Tamurello, glancing into the box, saw enough to warrant his interest and paid over Visbhume’s price.

Among the objects in the box were fragments of an old manuscript. When news of the transaction came by chance to the ears of the witch Desmei, she wondered if the fragments might not fill out the gaps in a manuscript which she had long been trying to restore. Without delay she took herself to Tamurello’s manse Paroli in the Forest of Tantrevalles, and there applied for permission to inspect the fragments.

With all courtesy Tamurello displayed the fragments. “Are these the missing pieces?”

Desmei looked through the fragments. “They are indeed!”

“In that case they are now yours,” said Tamurello. “Accept them with my compliments.”

“I will do so most gratefully!” said Desmei. As she packed the fragments into a portfolio, she studied Tamurello from the comer of her eye. She said: “It is somewhat odd that we have not met before.”

Tamurello smilingly agreed. “The world is long and wide. New experiences await us always, for the most part to our pleasure.” He inclined his head with unmistakable gallantry toward his guest.

“Nicely spoken, Tamurello!” said Desmei. “Truly, you are most gracious!”

“Only when circumstances warrant. Will you take refreshment? Here is a soft wine pressed from the Alhadra grape.”

For a time the two sat discussing themselves and their concepts. Desmei, finding Tamurello both stimulating and large with vitality, decided to take him for her lover.

Tamurello, who was keen for novelty, made no difficulties and matched her energy with his own, and for a season all was well. However, in due course Tamurello came to feel that Desmei, to an enervating degree, lacked both lightness and grace. He began to blow hot and cold, to Desmei’s deep concern. At first she chose to interpret his waning ardor as a lover’s teasing: the naughtiness, so to speak, of a pampered darling. She thrust herself upon his attention, tempting him with first one coy trick, then another.

Tamurello became ever more unresponsive. Desmei sat long hours with him, analyzing their relationship in all its phases, while Tamurello drank wine and looked moodily off through the trees.

Neither sighs nor sentiment, Desmei discovered, affected Tamurello. She learned that he was equally proof against cajolery, while reproaches seemed only to bore him. At last, in a facetious manner, Desmei spoke of a former lover who had caused her pain and hinted of the misfortunes which thereafter had dogged his life. Finally she saw that she had captured Tamurello’s attention, and veered to more cheerful topics.

Tamurello let prudence guide his conduct, and once again Desmei had no complaints.

After a hectic month Tamurello found that he could no longer maintain his glassy-eyed zest. Once again he began to avoid Desmei, but now that she understood the forces which guided his conduct, she brought him smartly to heel.

Desperate at last, Tamurello invoked a spell of ennui upon Desmei: an influence so quiet, gradual and unobtrusive that she never noticed its coming. She grew weary of the world, its sordid vanities, futile ambitions and pointless pleasures, but so strong was her disposition that she never thought to suspect a change in herself. From Tamurello’s point of view, the spell was a success.

For a period Desmei moved in gloomy contemplation through the windy halls of her palace on the beach near Ys, then at last decided to abandon the world to its own melancholy devices. She made herself ready for death, and from her terrace watched the sun set for the last time.

At midnight she sent a bubble of significance over the mountains to Faroli, but when dawn arrived, no message had returned.

Desmei pondered a long hour, and at last thought to wonder at the dejection which had brought her to such straits.

Her decision was irrevocable. In her final hour, however, she bestirred herself to work a set of wonderful formulations, the like of which had never been known before.

The motives for these final acts were then and thereafter beyond calculation, for her thinking had become vague and eerie. She surely felt betrayal and rancor, and no doubt a measure of spite, and seemed also urged by forces of sheer creativity. In any event she produced a pair of superlative objects, which perhaps she hoped might be accepted as the projection of her own ideal self, and that the beauty of these objects and their symbolism might be impinged upon Tamurello.

In the light of further circumstances* her success in this regard was flawed, and the triumph, if the word could so be used, went rather to Tamurello.

The details are chronicled in LYONESSE 1: Suldrun’s Garden.

In achieving her aims, Desmei used a variety of stuff: salt from the sea, soil from the summit of Mount Khambaste in Ethiopia, exudations and pastes, as well as elements of her personal substance. So she created a pair of wonderful beings: exemplars of all the graces and beauties. The woman was Melancthe; the man was Faude Carfilhiot.

Still all was not done. As the two stood naked and mindless in the workroom, the dross remaining in the vat yielded a rank green vapor. After a startled breath, Melancthe shrank back and spat the taste from her mouth. Carfilhiot, however, found the reek to his liking and inhaled it with all avidity.

Some years later, the castle Tintzin Fyral fell to the armies of Troicinet. Carfilhiot was captured and hanged from a grotesquely high gibbet, in order to send an unmistakably significant image toward both Tamurello at Faroli to the east and to King Casmir of Lyonesse, to the south.

In due course Carfilhiot’s corpse was lowered to the ground, placed on a pyre, and burned to the music of bagpipes and flutes. In the midst of the rejoicing the flames gave off a gout of foul green vapor, which, caught by the wind, blew out over the sea. Swirling low and mingling with spume from the waves, the fume condensed to become a green pearl which sank to the ocean floor, where eventually it was ingested by a large flounder.est part always breaks first. If I fixed the dead-eyes, then the

SOUTH ULFLAND FACED ON THE SEA from Ys in the south to Suarach in the north: a succession of shingle beaches and rocky headlands along a coast for the most part barren and bleak. The three best harbours were at Ys and Suarach and at Oaldes, between the two. Elsewhere harbours, good or bad were infrequent, and often no more than coves enclosed by the hook of a headland.

Twenty miles south of Oaldes, a line of crags entered the ocean and with the help of a stone breakwater, gave shelter to several dozen fishing boats. Around the harbour huddled the village Mynault: a clutch of narrow stone houses, two taverns and a marketplace.

In one of the houses lived the fisherman Sarles, a man black-haired and stocky, with heavy hips and a small round paunch. His face, which was round, pale and moony, showed, a constant frown of puzzlement, as if he found life and logic always at odds.

The bloom of Sarles’ youth was gone forever, but Sarles had little to show for his years of more or less diligent toil. Sarles blamed bad luck, although if his spouse Liba were to be believed, indolence was by far the larger factor.

Sarles kept his boat the Preval drawn up on the shingle directly in front of his house, which made for convenience. He had inherited the Preval from his father, and the craft was now old and worn, with every seam leaking and every joint working. Sarles well knew the deficiencies of the Preval and sailed it out upon the sea only when the weather was fine.

Liba, like Sarles, was somewhat portly. Though older than Sarles, she commanded far more energy and often asked him: “Why are you not out fishing today, like the other men?”

Sarles’ reply might be: “The wind is sure to pipe up later this afternoon; the dead-eyes on the port shrouds simply cannot take so much strain.’

“Then why not replace the dead-eyes? You have nothing better to do.”

“Bah, woman, you understand nothing of boats. The weak-shrouds might part, or a real blow might push the mast-step right through the bottom of the boat.”

“In that case, replace the shrouds, then repair the strakes.”

“Easier said than done! It would be a waste of time and I would be throwing good money after bad.”

“But you waste much time at the tavern where you also throw away good money, and by the handfuls.”

“Woman, enough! Would you deny me my single relaxation?”

“Indeed I would! Everyone else is out on the water while you sit in the sun catching flies. Your cousin Junt left the harbour before dawn to make sure of his mackerel! Why did you not do the same?”

“Junt does not suffer miseries of the back as I do,” muttered Sarles. “Also he sails the Lirlou, which is a fine new boat.”

“It is the fisherman who catches fish, not the boat. Junt brings in six times the catch you do.”

“Only because his son Tamas fishes beside him.”

“Which means that each out-fishes you three times over.”

Sarles cried out in anger: “Woman, when will you learn to curb your tongue? I would be off to the tavern this instant had I one coin to rub against another.”

“Why not use the leisure to repair the Prevail” Sarles threw his hands in the air and went down to the beach where he assessed the deficiences of his craft. With nothing better to do, he carved a new dead-eye for his shrouds. Cordage was too dear for his pocket, so he performed a set of makeshift splices, which strengthened the shrouds but made an unsightly display.

And so it went. Sarles gave the Preval only what maintenance was needed to keep it afloat, and sallied out among the reefs and rocks only when conditions were optimum, which was not often.

One day even Sarles became alarmed. With a soft breeze blowing on-shore, he rowed from the harbour, hoisted his sprit-sail, set up the back-stay, adjusted the sheets and bow nicely across the swells and out toward the reefs, where fish were most plentiful… . Peculiar! thought Sarles. Why did his back-stay sag when he had only just set it up taut? Making an investigation, he discovered a daunting fact: the stern-post to which the stay was attached had become so rotten from age and attacks of the worm that it was about to break loose to the tension of the back-stay, thereby causing a great disaster.

Sarles rolled up his eyes and gritted his teeth in annoyance. Now, without fail or delay, he must make a whole set of tedious repairs, and he could expect neither leisure nor wine-bibbing until the repairs were done. To finance the repairs he might even be forced to beg a place aboard the Lirlou, which again was most tiresome, since it meant that he would be forced to work Junt’s hours.

For the nonce, he shifted the back-stay to one of the stem-cleats, which, in mild weather such as that of today, would suffice.

Sarles fished for two hours, during which time he caught a single flounder. When he cleaned the fish, its belly fell open and out rolled a magnificent green pearl, of a quality far beyond Sarles’ experience. Marvelling at his good fortune, he again threw out his lines but now the breeze began to freshen, and concerned with the state of his makeshift back-stay, Sarles hoisted anchor, raised his sail and turned his bow toward Mynault, and as he sailed he gloated upon the beautiful green pearl, the very touch of which sent shivers of delight along his nerves.

Once more in the harbour, Sarles beached his boat and set out for home, only to meet his cousin Junt.

“What?” cried Junt. “Back so soon from your work? It is not yet noon! What have you caught? A single flounder? Sarles, you will die in penury if you do not take yourself in hand! Truly you should give the Preval a good work-over and then fish with zeal, so that you may do something for yourself and your old age.”

Nettled by the criticism, Sarles retorted: “What of you? Why are you not out in your fine Lirlou? Do you fear a bit of wind?”

“Not at all! I would fish and gladly, wind or no wind, but for caulking and fresh pitch done to Lirlou’s seams.”

As a rule Sarles was neither clever, spiteful, nor mischievous, his worst vice being sloth and a surly obstinacy in the face of chiding from his spouse. But now, impelled by a sudden tingle of crafty malice, he said: “Well then, if zeal rives you so urgently, there is the Preval; sail out to the reef and fish until you have had enough.”

Junt gave a derisive grunt. “It is a sad comedown for me after working my fine Lirlou. Still, I believe that I will take you at your word. It is odd, but I cannot sleep well unless I have rousted up a good catch of fish from the deep.”

“I wish you good luck,” said Sarles and continued along the jetty. The wind, so he noted, had shifted and now blew from the north.

At the market Sarles sold his flounder for a decent price, then paused to reflect. He pulled the pearl from his pocket and considered it anew: a beautiful thing, though the green luster was unusual and even… it must be admitted… a trifle unsettling.