Elizabeth M. Norman

Read Elizabeth M. Norman Online

Authors: We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan

Tags: #World War II, #Social Science, #General, #Military, #Women's Studies, #History

Also by Elizabeth M. Norman

Women at War: The Story of

Fifty Military Nurses

Who Served in Vietnam

Copyright © 1999 by Elizabeth M. Norman

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Norman, Elizabeth M.

We band of angels: the untold story of American nurses trapped on Bataan by the Japanese/by Elizabeth M. Norman.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79957-9

1. World War, 1939–1945—Medical care—United States.

2. World War, 1939–1945—Prisoners and prisons, Japanese.

3. Prisoners of war—Philippines—History—20th century.

4. Nurses—United States—History—20th century. I. Title.

D807.U6N58 1999 940.54′7573—dc21 98-45998

Random House website address:

www.atrandom.com

v3.1

To Michael, Joshua and Benjamin

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

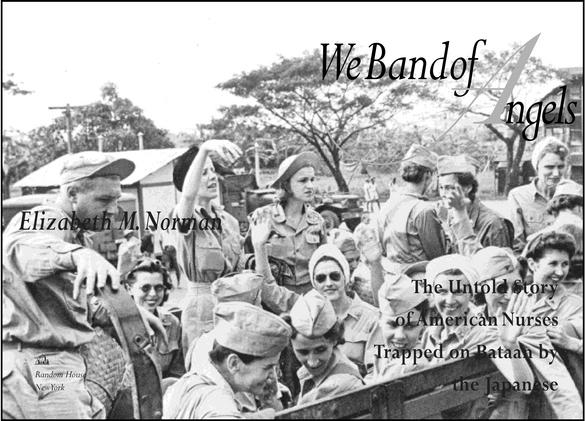

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Maps

1. Waking Up to War

2. Manila Cannot Hold

3. Jungle Hospital #1

4. The Sick, the Wounded, the Work of War

5. Waiting for the Help That Never Came

6. “There Must Be No Thought of Surrender”

7. Bataan Falls: The Wounded Are Left in Their Beds

8. Corregidor—the Last Stand

9. A Handful Go Home

10. In Enemy Hands

11. Santo Tomas

12. STIC, the First Year, 1942

13. Los Banos, 1943

14. Eating Weeds Fried in Cold Cream, 1944

15. And the Gates Came Crashing Down

16. “Home. We’re Really Home.”

17. Aftermath

18. Across the Years

Afterword

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Appendix I: Chronology of Military Nurses in the Philippine Islands, 1940–1945

Appendix II: The Nurses and Their Hometowns

Bibliography

Endnotes

About the Author

Foreword

I

CANNOT SAY

where or when, exactly, this story really began. Sometimes, I think it started with my mother.

Dorothy Riley Dempsey served as a SPAR in the Coast Guard in World War II. Growing up, my four sisters and I heard a lot about our mother’s days in uniform, holding down Stateside duties to free the men to go to sea, but it was hard to think of Mom as a “military woman.” The term always seemed an oxymoron to me. In fact, it was hard to think of any woman in such a “man’s world,” a domain I thought was antithetical to everything a woman was, or was supposed to be: wife, mother, sister, friend.

Then early in my academic career I interviewed fifty women who had served as military nurses in Vietnam. As a registered nurse I became fascinated by their stories, stories of dying soldiers and wounded children, of exhaustion, frustration and fear. They said their experiences—caring for the sick and wounded, sorting out mass casualties, suffering rocket and artillery attacks—changed them. War, they told me, was their life’s dividing line.

I wondered: Was it the bizarre and tragic nature of Vietnam that made these women seem so different from the other nurses I had worked with across the years, or was the difference the result of women trying to live and work in a domain almost exclusive to men, women trying to adapt to what has always been a man’s enterprise, war?

During my research on Vietnam I kept coming across references to a small group of women who had “fought” in World War II, a group commonly referred to as the Angels of Bataan and Corregidor. To follow up I called Brigadier General Lillian Dunlap, a retired chief of the Army

Nurse Corps. What she said that morning started me on a search that has taken me eight long years to complete.

T

HE SAME DAY

the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its surprise attack on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii it also struck American naval and army bases, airfields and ports in the Philippine Islands—December 8, 1941.

1

Caught in the air raid and the murderous invasion that followed were ninety-nine army and navy nurses. Without any formal combat training or wartime preparation, most found themselves on Bataan with their backs to the sea, retreating from a well-trained, well-supplied and relentless army. They were hungry and scared, jumping into trenches during bombing raids, caring for thousands of casualties. Before the enemy finally caught up with them on Corregidor, a handful of the women—some two dozen—escaped on ships or small aircraft that managed to slip through the enemy blockade. The main body, however—seventy-seven women, a group in many ways representative of American womanhood in the era between the great wars—were captured by the Japanese and held behind concrete and barbed wire for three years in prison camps.

As a unit the nurses of Bataan and Corregidor represent the first large group of American women in combat and the first group of American military women taken captive and imprisoned by an enemy.

Thinking of my mother, a strong purposeful woman, and thinking of the nurses of Vietnam, a group struggling to reconcile their notions of women’s identity with their experience in war, I knew the Angels’ story would be compelling and decided to go after it.

General Dunlap had given me phone numbers for two of the Angels, and in the spring of 1989 I called them, offered my background and explained my purpose. At length they agreed to sit down and talk. Their willingness to cooperate came, I’m sure, from our sorority—nurse talking to nurse—but I also got the sense that these women were painfully aware that their ranks were dying, and that if they did not speak out now, if they did not attempt to preserve their dark but wonderful story, it would disappear. In short they did not want their legacy folded into the larger story of World War II and lost in the often indiscriminate pages of history.

So I set out to visit the two women the general had recommended to see if there was a story I could tell. At first I wondered about their ability to recall in detail events and relationships some fifty years old. To my

surprise, and embarrassment, both women, Mary Rose Harrington Nelson, a former navy nurse in her late seventies, and Ruby Bradley, a retired army nurse in her mid-eighties, were often encyclopedic in their accounts, and I sat there rapt as they took me back to their war and the trials of their survival.

Each woman also supplied me with names and addresses of her comrades, but told me to hurry because time was taking them. Old and enervated by their long captivity, the group was dying. At the time, January 1990, only forty-eight of the original seventy-seven captured in 1942 and repatriated in 1945 were still alive.

I quickly began to arrange visits. Several times my fears about the Angels’ advancing age and ill health proved true. In January 1992 one of them, Bertha Dworsky of Sunnyvale, California, apologized and said she could not see me. “I’m eighty-one years old,” she wrote, “and it’s all I can do to take care of myself.”

2

A month later, she was dead. Another woman, Ruth Straub from Colorado Springs, went into a hospital the day before I was scheduled to sit down with her. After that I rushed to find Josephine Nesbit, a senior army nurse and a central figure in the story. Her husband, Bill Davis, called to say his wife was too weak from a recent heart attack to talk. Then I wrote a letter to Inez McDonald Moore in San Marcus, Texas. A week or so passed and an envelope arrived bearing her return address. I opened it to find a note from her husband and a clipping—Inez’s obituary. Nine other women died before I could find and contact them.

Three of the forty-eight refused to see me. “It was too long ago and too hard to remember,” one said.

3

Another wrote, “I regret that I am not able to assist you. I do not want to live in the past.”

4

About a dozen were simply impossible to locate, lost to time or circumstance.

In the end I spoke with twenty of the women, all generous with their time and their memories. We talked in their homes or in the retirement centers they called home. I filled out these personal accounts with scores of additional interviews—other veterans, government officials, the Angels’ children and relatives.

Early in my search I noticed that the interviews seemed to take on a pattern. They always began with humor—something I had noticed in my interviews of the women from Vietnam. I have spoken with other war writers about this, why those who have seen heavy combat mask their grim vitae with jokes and rhetorical slapstick. I think it is a way for them to introduce the idea of living with the absurd or of taking part in the unthinkable.

Or perhaps the jokes are a way to keep the loss and the savagery from overwhelming them. Several nurses, for example, told me the same raucous prewar story about a particularly self-possessed nurse in a bar who became so angry at the soldier interrupting her quiet beer, she slugged him and knocked him out.

When we finally got past the “fun” and turned to the real fighting, many found it extremely painful to talk about their losses—the loss of their youth, health, patients, battlefield husbands and boyfriends. A few broke down and wept as they recalled the helplessness they felt watching the enemy pull the wounded from their hospital beds and cart them to certain death in a military prison. Nothing, nothing at all, is more devastating to a nurse than to be pulled away from the patients in her charge, the lives entrusted to her.

The more I studied the women, the more I realized I was dealing not with individuals but with a collective persona. The women often answered my questions using the pronoun “we” rather than “I.” They were some of the least egocentric people I’ve met and as such were difficult interviews. Many simply did not want to talk about themselves. They did not have the habit of self-reflection that seems to drive the conversation of our era, the need to dwell on identity, to indulge the ego and see all stories as memoir. Rather they insisted on emphasizing their connections, their relationships with one another—a turn of mind made familiar to the modern woman by the research of social psychologists. And so their individual stories were sketchy, too sketchy for full-length profiles or portraits, but when those stories were put together, the Angels seemed to come to life. So I let them teach me the way, and the way was to consider their experience as a group, an identification of their own making.