Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine 09/01/12 (6 page)

Read Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine 09/01/12 Online

Authors: Dell Magazines

With a vengeance.

A good man driven

to crime is an old, familiar story, from

Robin Hood

to

Breaking

Bad.

It wasn’t hard to sell.

Desperate for money, Max had gone into

the drug trade. The brick of crystal meth the Staties found hidden in his garage was

the proof. Working on a story about meth labs, Sherry discovered his involvement.

She confronted him at the turnout, hoping he would give himself up.

Instead,

he killed her. He admitted it all to me before dying in a desperate shootout.

Resisting arrest isn’t suicide. If the two Staties had any doubts, they vanished

when I showed them the map of the meth labs I’d recovered from Max’s body.

The

story was a total crock, but it was plausible, and seamless. And they bought

it.

The raids on the crank labs began at dawn the next day and continued

through the week. The state police and DEA rolled up eight labs and a dozen cookers.

It made national news. Which was the second point of the exercise.

Helping

Margo collect the insurance money her man had died for wasn’t the only reason I sold

the state police a bill of goods. It was my last chance to give Sherry what she’d

always needed so desperately. More than anything in this world, she’d wanted to be a

star.

By God, she went out as one.

My version of events conveniently

omitted her complicated love life. Instead, Sherry died as a courageous newswoman

hot on the trail of a big story.

I think Zee knew better, but by the time she

wrapped up her own investigation, the raids were already underway and my fairy tale

had gone viral in the media. On the Net, facts never get in the way of a good

story.

Desperate for a heroine after the recent scandals, the national press

turned Sherry into an instant icon. Overnight, her dream came true. Everyone knew

her name. She was the center of attention.

It won’t last, of course. Andy

Warhol set fame’s expiration date at fifteen minutes, and most of us never achieve

that.

But Sherry got her share and then some. Her funeral was a media circus.

Talking heads from the major networks and most of the minors covered it live from

the cemetery, wearing somber faces and black armbands.

It was a spectacular,

star-spangled sendoff. I only wish she could have seen it.

And maybe she

did.

I’m not religious. The afterlife is a mystery to me. But I knew Sherry

down to the bone. Knew her drive and her desperation.

No power in this world

or the next could have kept her away from that show. In my heart, I know she saw

that turnout, and warmed herself in the spotlight one last time.

And if you

could ask her if it was worth it?

I know exactly what she’d say.

Copyright © 2012 by Doug Allyn

by Susan Lanigan

The

short fiction of Irish author Susan Lanigan has appeared in a variety of

publications, including

The Stinging Fly, Southword, The Sunday

Tribune,

the

Irish Independent,

and

The Mayo News.

She has been shortlisted twice for the Hennessy New Irish Writing Award and has

won several other awards.

Nature

magazine’s science-fiction section

recently acquired two of her stories and her work is featured in the

science-fiction anthology

Music For Another

World.

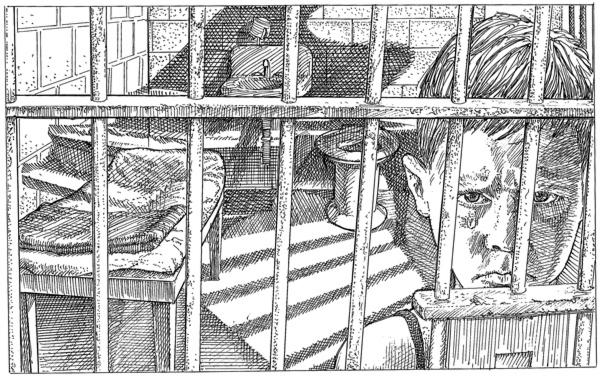

Once again, the sunset. To be precise, the bit I

am allowed to see: parallel gold diagonals streaking across the edge of my bunk and

hitting the door, while the sink and privy stay in the dark and the mirror reflects

nothing. I prefer the shadow. Since they moved me here five years ago, a kindly

promotion from the cell that faced the prison’s north wall, I have seen too many

sunsets, each one leading back to the same memory: my mother, long dead now, playing

the piano.

She always became more girlish when she played; even then I

noticed the shy hesitant smile when she made the odd mistake. I was five then,

standing in the doorway of the study in a manner, Dearbhla told me afterwards, of a

child self-consciously trying to be “cute.” I have no idea whether Dearbhla told me

this out of malice—whether she already detected a resentment I could find no words

to express—or because she was genuinely amused. Anyway, she was not there to witness

it firsthand. By the time she was there on a regular basis, my mother and her orange

kaftans and hair tied back with a grubby chenille ribbon had gone, gone

forever.

My mother had few pieces in her repertoire but since I, at the age of

five, was her primary listener, it should not have mattered too much. Yet I recall,

in flashes, how her head would jerk upwards when my father pushed the creaking gate

of our little garden open. The look of strained hope that crossed her face as she

pushed the open window full out and started a few bars of the same piece. She

started

in medias res,

I believe, to fool my father into thinking that she

had been playing on for hours, unaware of his presence, in some sort of creative

trance. I don’t believe he fell for it. He would come to the door and wink at me as

she fingered the keys like alien objects, her eyes self-consciously shut.

It

was always the same piece, Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, and she was never able to get

all the way through without making a mistake. To me now, that seems absurd; unlike

Dearbhla, I never had a great talent for music, but even I could pick my way through

something of that level with no great difficulty. But my mother’s mistakes were

always so small—a missed note when it unexpectedly changed to F minor on the second

repetition, an E instead of a D in the bass—that somehow I could always hear the

soft chords transcending the little awkwardnesses. I remember (this must have been

earlier, I must have been even younger then) hearing the muffled ripple of bass and

right-hand chords through the timber of the shivering piano as I curled myself into

a ball at my mother’s feet. I nearly fell asleep with my cheek touching the cold

bronze of the

una corda

pedal, spittle drooling down my cheek. The evening

sun was coming through the two-paned window, shafts of it warming the wood, and

warming my mother’s orange kaftan and warming the pale brown carpet where I lay my

head. The soft pedal remained cold, unmoving. I don’t know how long I lay there

until I was picked up and brought to bed. It seemed like infinity, but then again

this happened long ago, before I learned to measure time, each begrudging second,

hour, and year of it.

She never quite got it right. Each rendition was a

diamond with a different flaw. I didn’t mind. Like an idiot savant, I craved

routine. The routine of sun falling on my mother and the Gymnopédie, the routine of

drizzle soaking the unmown grass in our front garden and the Gymnopédie, the dying

elm shedding its last leaves as the Dutch beetle gnawed away at it from the

inside—and the Gymnopédie—

“I’ll get it,” my mother would call out, “I will,

you’ll see.” Then she would fling her head back and laugh, and the light would catch

the fine hairs on her neck, her neck that was able to arch so elegantly and make my

father catch his breath. Dearbhla says I don’t remember properly, after all I was

very young and children idealise things a lot, don’t they? But then again, rare

things are easy to recall by virtue of their rareness—and happy memories of my

childhood are rare indeed.

I don’t know why Dearbhla still visits me,

week in, week out. I should be the last person she wants to see. She is a joy to

look at through the Perspex panel: those tapering, gloved fingers are still

beautiful, their clasp of the thin, unlit cigarette irreproachably filmic. They will

never touch a piano again. But even in late middle age she retains the proud cheeks

and prominent eyes that captivated her audience as much as the pieces she performed

for them. The last time she came, she brought a letter in a vellum envelope. Typed,

of course; she can hardly write by hand now. I haven’t read it yet. I want to hold

off as long as possible to make the anticipation all the keener. Prison has taught

me discipline, the ability to ration pleasure. She arrives again tomorrow: I will

have read it by then.

She has forgiven me much, Dearbhla, or perhaps she

visits me out of need: I am the only surviving witness of the great tragedy of her

life. As long as she blames me, she is safe. She can duck responsibility for her one

failure.

Perhaps she is correct. Perhaps it is my fault.

When

Dearbhla first came to the house, the laughter was different. It was laughter that

sounded as if it were trapped in a bad sitcom and never let out. It banged crossly

against the china my mother brought out for her visitor and rat-tatted irritably

against the walls.

Dearbhla sat on the edge of one of our armchairs, her eyes

eager, hands holding her cup in a way that spoke pure elegance. My mother, her face

white and strained, her hair still pulled back in the grubby ribbon, had lost her

look of girlishness. Her belly rounded out a little and her neck no longer arched

the way it used to. When my father propelled me forward to Dearbhla and boomed at me

to say hello, I was crushed in silk and perfume and Dearbhla’s slightly harsh voice

breathed affectionately in my ear, “Well,

there’s

the darling.”

Her

presence unsettled me. It was as if something alien, wondrous, and scary had come

into our little cottage, enveloping it with an aura I had never experienced before.

When I had lain under my mother’s feet back then, I had felt such security, but in

Dearbhla’s arms I sensed danger and excitement. Her embrace was too cloying and yet

delightfully warm, her fingers wrapped around me and dug in like claws. I looked

over to my mother’s fingers, which were lacing and unlacing each other in tension. I

saw how short and spatulate they were. Fingers that would get lost playing the

difficult octave spans that Dearbhla was to show me, though I could not know that at

the time.

It was my father who first suggested that Dearbhla play something.

She smiled, but looked uncomfortable at the suggestion. “Oh David. Should I,

really?” I could tell from the tautness of her body, still holding mine, that she

longed for it, but did not dare say yes. Not openly. Not yet.

But my father,

his voice queer and rough, said, “Yes. Play. Play!” His command was heavy with a

weird ache.

“Well,” Dearbhla said. “If you insist.”

My mother’s eyes

widened. The pupils in them had shrunk into tiny black dots and they were all iris.

She stood up in a jerky, unlovely movement, walked over to Dearbhla’s chair, and

pulled me out of her arms. I squeaked with alarm.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” Dearbhla

said good-humouredly, getting out of the chair.

I could tell my father was

about to say something to my mother, but then Dearbhla sat down at the stool, her

fingers running lightly over the keys without pressing them. I shuddered as they did

so, imagining them clinging hard to me, even though her touch on the keyboard was

delicate. I looked over at my father. His eyes were closed, lips parted open. Now it

was he who looked as if he were in a trance.

“What shall I play?” Dearbhla

asked gaily.

“Anything,” my father whispered.

I did not look at my

mother.

After what seemed like an age, Dearbhla hit two black keys and then

let loose. I was later to learn that the piece was a Fantasie-Impromptu in C sharp

minor by Chopin, but at the time it was just a roaring tumble of notes, all pouring

out sweetly and asynchronously into the air. The energy in the room changed as she

played. Her eyes glazed over as left and right hand concentrated on maintaining the

difficult cross signatures the composer demanded.

My limbs were stiff with

awe, almost rooted, though I felt the urge to pee. I’d barely shifted when my father

placed a hand on my shoulder. He shook his head briefly, curtly. I stayed to listen

to Dearbhla play.

It ran down my leg. I felt the trickle seep through my red

cord dungarees, warm, burning, immediate. The music enraptured me so that I felt no

shame. Dearbhla and my father remained oblivious also. But Mother was not of that

world, and saw.

“That child.” She pointed at me. “Look at those wet pants.

Look at them.”

Dearbhla stopped playing.

“David,” my mother continued,

glaring at my father. “Are you going to do something? Look at those wet pants.

They’re disgusting.”

I was embarrassed, not for myself, though my thighs were

beginning to chafe with the urinous sting, but for my mother. Even at that young

age, I sensed that she, not I, was in the wrong, that her motives for humiliating me

were suspect.

“Ah, don’t worry, Lily,” Dearbhla said, getting up. “It was an

accident. It could happen to any child.”

My mother stood up too and faced

Dearbhla. For a moment, it looked as if she were going to hit her. My father sat

down, crossed his legs, and folded his arms. The moment seemed interminable. Then my

mother crossed over to the piano and sat on the stool, breathing

heavily.

“Lily, for God’s sake.” My father was angry now.

Ignoring him,

my mother breathed in a sob, pulled her hair ever more fiercely into a ponytail, and

launched into—yes, you guessed it, same old same old—the Gymnopédie. Her playing it

all wrong made it even worse. As she made mistake after mistake, she started to cry

openly. At the major seventh chord that resolves into the final D, she made the

worst clanger of the lot, hitting an F sharp and then going to the wrong place in

the bass. I prayed she would stop, but no, she kept going. Dearbhla, to give the

woman her due, kept her face an emotionless cast as the whole miserable,

cringe-inducing ritual dragged on.

“Lily, stop.”

“No, I won’t. I won’t

stop. And I won’t have that woman telling me how to rear my

children.”

Dearbhla gasped discreetly.

“Now,” my mother looked at me,

“I’m going to finish my piece. Your favourite, honey, remember?”

I felt my

voice come from a very faraway place.

“No. It’s not my favourite. I like

Dearbhla’s better. And you were mean to me in front of people. Daddy

told

me not to go to the bathroom. And,” I felt my father’s and Dearbhla’s relief and

satisfaction surge towards me even though their faces still betrayed nothing, “you

don’t play it right. You make mistakes. Dearbhla never makes mistakes.”

For

the last fifteen years I have regretted saying those words. Perhaps if I had stayed

silent, none of this would have happened.

There is little else to

remember about my mother. A few weeks later, I remember my father buying ice creams

for everyone. She burst into tears. He asked her what was wrong with the ice cream.

I joined in, also angry at her always crying and ruining our fun. We couldn’t do

anything without her crying now. I came to dread her presence.

She puked up

her ice cream.

All

of it, in a yellow-white mess, over the kitchen table.

It had that sharp hydrochloric smell of vomited food and I couldn’t bear to eat any

more of mine after that. I didn’t understand about morning sickness then. As my

father cleaned up, his mouth was twisted in disapproval, a disapproval I

shared.

Another day she shouted at him, in front of me, “Why won’t you love

me? Why do you go to

her

all the time?”

I thought my father would

shout back, the way he had once or twice before then, but no, he just cleared his

throat and left the room. I didn’t understand why he wasn’t angry, but something in

his demeanour made me terribly afraid all the same. As a child, I did not understand

what it is to be indifferent to someone: I do now. The years I’ve spent in this

place have flattened me out pretty well, to the point where I am pleased to say I am

indifferent to almost everybody.