Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852’1912 (76 page)

Read Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852’1912 Online

Authors: Donald Keene

Tags: #History/Asia/General

The Japanese army advancing near Weihaiwei. Print by Kobayashi Kiyochika(1895). More Japanese soldiers died from the bitterly cold winter than from Chinese bullets.

Courtesy the Kanagawa Museum

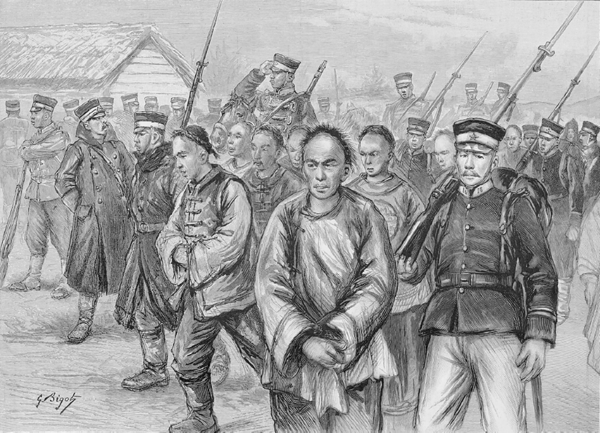

Japanese troops convoying Chinese prisoners. Lithograph by Georges Bigot (1895).

Courtesy Donald Keene

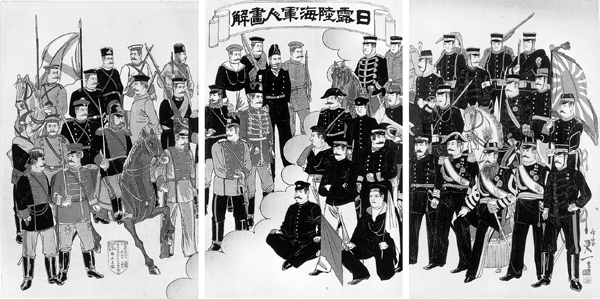

Russian and Japanese military at the outset of the Russo-Japanese War. Print by Watanabe Nobukazu (1904). The soldiers and sailors of the two nations are facially almost indistinguishable.

Courtesy Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Chapter 33

The customary New Year ceremonies for 1880 were performed by the emperor, now in his twenty-ninth year. The emperor and empress received the duke of Genoa, and Prince Heinrich, the grandson of the German kaiser, telegraphed greetings from his ship in Nagasaki harbor. On the second day of the new year Emperor Meiji sent a telegram of congratulations to Alfonso XII, the king of Spain, not on the New Year, but on his having escaped assassination.

1

More than ever, Meiji was in communication with the crowned heads of Europe, but he may have felt, even as he expressed joy over the narrow escapes of various kings, how remote their world was from his own; surely he had no fears that anyone would attempt to assassinate him.

This was the first year in which Meiji might be said to have routinely exercised his powers as emperor. His councillors’ proposals were brought to him for a final decision, not (as in previous years) as a mere formality, but because his opinion was needed, often to break a deadlock within the cabinet. This new responsibility may account for the reduction in his other activities. There was a marked decrease, for example, in the emperor’s visits to the empress dowager and in the number of times he went horseback riding. His formal education also suffered: he listened to lectures delivered by Motoda Nagazane and other scholars only twenty-three times between April and December, despite being scheduled to hear them four or five times each week. Instead, Meiji attended meetings of the cabinet almost every day,

2

and he had frequent lunch meetings with high-ranking officers of the government to discuss state business. It

ō

Hirobumi was particularly eager at this time to establish direct links between the emperor and the cabinet and for the emperor to assume a major role in decision making.

3

Financial problems were a principal concern of the government during 1880. Government revenues were far from covering expenditures. Although in the previous March the emperor had commanded the ministers, councillors, and others to practice strict economy and had given orders to the imperial household minister for the palace to serve as a model to the nation in its avoidance of wasteful expenses, his orders had little effect. The different ministries insisted that they were unable to cut expenses any further, and the palace’s expenses reportedly had actually increased. This was partly due to inflation, but the news prompted another call for economy: the staff was ordered to refrain from having repairs made to the palace that were not absolutely urgent and not to buy anything new.

Believing that a more positive policy than thriftiness was needed to overcome the financial problems,

Ō

kuma Shigenobu submitted in June 1879 a four-point proposal for remedying the situation. The first point was to redeem a considerable part of the paper money that had been printed to pay the expenses of the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion. The flood of banknotes had resulted in a loss of confidence in their value, and now a silver 1-yen coin was worth 1 yen, 43 sen in paper money. Inflation was rampant, and the only way to restore confidence in the banknotes was to replace nonconvertible notes with notes convertible into specie. The money for redeeming the notes could be raised in part by selling government-owned factories, but

Ō

kuma’s main proposal was to float a foreign loan of 50 million yen to be repaid over twenty-five years. He estimated that these measures would permit the government to redeem 78 million yen in nonconvertible notes.

4

Another 27 million yen in paper money would be redeemed in exchange for convertible bills.

The cabinet was evenly divided on the issue of whether to float a foreign loan.

Ō

kuma had won over the Satsuma faction, but the Ch

ō

sh

ū

and allied councillors, headed by It

ō

Hirobumi, opposed the loan, though not all for the same reasons. Among the strongest opponents was Minister of the Right Iwakura Tomomi, who (as a member of the nobility) was in constant communication with the palace. His allies among the former

jiho

, especially Sasaki Takayuki and Motoda Nagazane, also continued to have access to the emperor’s ear. Motoda spoke strongly against any foreign loan, conjuring up the peril to the nation that this might involve and recalling General Grant’s warning against accepting foreign money. The question he (and Iwakura) posed was, what if Japan were unable to repay the loan? Would Japan have to yield part of its territory—say, Shikoku or Ky

ū

sh

ū

—in order to satisfy its creditors?

5

The only way to overcome the financial crisis, these men argued, was to practice strict economy.

The emperor was aware of

Ō

kuma’s plan and did not like it, but he was also anxious not to risk a permanent split in the cabinet, such as had occurred at the time of the dispute over Korea. He sought the opinions of the heads of the different ministries, but they also were divided. Unable to get a clear recommendation either way, the emperor finally decided against borrowing money from foreign countries. On June 3, 1880, he issued this rescript:

Ever since the early years of the Meiji era, there have been many demands on the state that have brought about the present financial difficulties. Today, in the thirteenth year of the era, there is an outward flow of specie, resulting in a loss of confidence in paper money. This was the reason for Councillor

Ō

kuma’s proposal. I have examined this proposal. I have also been informed that there is no unanimity of opinion in the cabinet or in the various ministries. Although I am well aware that it is not easy to dispose of the financial problem, I am convinced that borrowing money from abroad is today an inadmissible solution. Last year Grant spoke at length concerning the advantages and disadvantages of foreign loans. His words are still in my ears. The financial crisis looms before us today, and we must choose a goal for the future. Now is the time for putting thrift into practice. I call on you, my lords, to implement my wishes and, making strict economy your watchword, establish a course for economic recovery. Discuss this fully with the cabinet and ministries, then report back to me.

6

There was naturally no opposition to the emperor’s command, although there was discussion about how to implement it. The emperor’s decision in effect had established the palace as the ultimate authority when divisions existed in the cabinet and ministries. Before long, a similar decision would be required of the emperor with respect to the proposal that in order to control the mounting price of rice, the farmers should be required to pay taxes in rice rather than in cash, reverting to the system that had existed under the shoguns. But before this problem came to a head, the emperor set out on another progress, this one to Yamanashi, Mie, and Ky

ō

to Prefectures.

7

The announcement of the forthcoming journey, made on March 30, set the date for his departure on June 16. In May the people of the Shimo-ina district of Nagano sent a petition to the emperor imploring him to travel through their backward part of the country rather than through Kiso, which already had a fine road and might soon expect the railway. Such a visit would serve to stimulate the production of silk, the local industry, and would give women and children, who could not hope to visit the capital even once in their lifetimes, an unforgettable experience.

8

Although the emperor did not accept the petition, it suggests the people’s eagerness for the emperor to visit their region.

In preparation for the emperor’s travels, the roads were improved. For example, the road beyond Sasago, formerly a perilous trail into the mountains, had been widened and railings erected at places where there was a sharp drop below.

9

The cost of mending the roads over which the procession would pass soon became the subject of conflicting statements by the newspapers and the authorities. According to one newspaper, each household in the district was required to pay part of the cost of improving the road and of providing flags, roadside lighting, and the like. It was reported that many people, though delighted at the prospect of worshiping the emperor as he passed, had complained that even if they sold all their possessions, they would not be able to raise the 3 yen, 53 sen, 3 rin that was their share of the expenses.

10

The headman of the town of Kita Fukashi, however, denied that vast sums of money were being spent in preparation for the emperor’s visit. He insisted that no levy had been imposed on the population, that the expenses would be paid by public-spirited persons.

11

Perhaps the most striking editorial on the emperor’s proposed journey appeared in the

T

ō

ky

ō

Yokohama mainichi shimbun

on April 4. The writer drew a distinction between necessary and unnecessary travels by the emperor. At the beginning of his reign when people in such places as the northeast or in Ky

ū

sh

ū

were unaware there was an emperor who ranked even higher than their feudal lords, it was necessary for him to journey to these places to make people aware of his existence. However, the editorial continued,