Empire of Sin (27 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

A

ND

so the vice mills of Storyville rolled on more or less unchecked. Lulu White, Emma Johnson, and Willie Piazza continued to do business on Basin Street, within plain sight of the passengers arriving at the Frisco depot. In the dives and dance halls of Franklin Street, Freddie Keppard, “Big Eye” Louis Nelson, and the young wunderkind Sidney Bechet continued to play their new music to mixed audiences, provided there was an old ham sandwich on the premises. But for one Storyville icon, life had changed. A few years after her evening with Carrie Nation,

Josie Arlington had retired and left the profession as promised. She leased the Basin Street brothel to her former housekeeper, Anna Casey, but retained ownership, thereby ensuring an ample revenue stream to support the family’s luxurious new life on Esplanade Avenue. And though her plans to build a home for wayward girls were apparently on hold (and would in fact never come to fruition), she was now at least free of the taint of Basin Street in all ways but financial. She and her beloved niece Anna could spend all of their time together now, shopping, gardening, making excursions to Anna’s Villa in Covington, and generally living the life of just the kind of respectable upper-class family that Anna still believed she belonged to.

For the woman now known to the world as Mrs. John Thomas Brady, this transformation must have come with overtones of revenge. Her yearnings for respectability had always seemed shaded by a certain contempt for those born into the condition naturally, and this contempt had erupted memorably on at least one occasion late in her career. According to hoary Storyville legend, the queen of the demimonde had by 1906 come to resent the daring young persons of socially prominent families who would show up incognito at Tom Anderson’s annual Mardi Gras fete, the Ball of the Two Well Known Gentlemen. Masked in Carnival regalia, these slumming voyeurs would gape condescendingly at the colorful revels of fallen women and their sporting men, all while remaining safely anonymous behind their masks. “

Josie Arlington solved the problem,” one Storyville chronicler explained, “by arranging for the police to raid the affair and to arrest any woman who did not carry a card registering her as a prostitute in good standing. The stratagem caused great embarrassment to the large number of ladies of New Orleans ‘high society’ who were summarily carted off to the police station, unmasked, and sent home.” But now, in 1909, Arlington had an even sweeter revenge: those society ladies who enjoyed masquerading as prostitutes for a night would now have to tolerate a prostitute masquerading as a society lady for the rest of her life.

But Mrs. Brady seemed capable of extracting only so much pleasure from her new life of respectability. According to reports from friends and associates, the retired madam became

increasingly morbid and religious over the next few years. Eventually, she spent $8,000 on

an elaborate red-marble tomb in Metairie Cemetery. Flanked by two imposing stone flambeaux, the miniature temple featured elegant carvings and bas-reliefs front and back. At the doors to the tomb stood a statue of a beautiful young woman carrying an armful of roses, her other hand placed against the door as if in the act of pushing it open.

Mrs. Brady had meanwhile decided to devote the rest of her life to the cultivation of her adored niece. “

I am living only for Anna,” she confided to a friend, and indeed, the two women were reportedly inseparable now. At one point, Mrs. Brady confessed that she would rue the day that Anna finally got married. When the girl asked why, her aunt said simply, “

Because men are dogs.”

For a woman who’d spent her entire life catering to the carnal desires of thousands of men, the sentiment was perhaps understandable. But Anna was now in her mid-twenties. How much longer could even the most sheltered innocent be kept in ignorance of the basic facts of her own deceptively privileged life?

B

Y

1910, it had become clear that reformers generally—and Philip Werlein in particular—were not going to give up their campaign against Storyville. Their proposals to screen off the District and to move the Basin Street brothels had proven both unpopular and politically untenable. But now Werlein, armed with the provisions of the Gay-Shattuck Law, decided to try a new tack. And it would center on the one issue about which moral reformers, business reformers, and machine politicians were all of one mind—race: “

The one thing that all Southerners agree upon is the necessity of preserving our racial purity,” Werlein told reporters in early February. “The open association of white men and Negro women on Basin Street, which is now permitted by our authorities, should fill us with shame as it fills the visitor from the North with amazement.”

In the Gay-Shattuck Law, which forbade any alcohol purveyor from serving both blacks and whites in the same building, and in another 1908 law against interracial concubinage, Werlein thought he had the ammunition needed to abolish at least the so-called octoroon houses, and he was willing to use it. “I will enlist the aid of every minister in New Orleans,” he vowed. “I am determined to arouse public sentiment against the awful conditions which exist.… It is a shame and a disgrace that Negro dives like those of Emma Johnson, Willie Piazza, and Lulu White, whose infamy is linked abroad with the fair name of New Orleans, should be allowed to exist and to boldly stare respectable people in the face.” His conclusion: “These resorts should be exterminated, and the Negresses who run them driven from the city.”

The war against Storyville thus entered a new and particularly ugly stage. Until now, the District had been a lone holdout in the overall movement in New Orleans toward greater repression of African Americans. Black men had never been allowed to come to Storyville proper as brothel customers (even the black crib prostitutes were available to whites only), but they had always been able to work, dance, and drink there. And certainly sexual congress between white men and black women had not only been allowed but actively encouraged and advertised. All of this, however, was to change over the next few years, as reformers attempted to move the city closer to traditional Southern norms of racial regimentation. Life in Storyville—as both blacks

and

whites had known it—was about to change.

But perhaps the greatest threat to the District would come not from those who wanted to destroy it but rather from those who wanted to exploit it. For the remarkable success of Storyville had not gone unnoticed in the criminal underworlds in the rest of the country. A number of gangsters from places like New York and Chicago had been arriving in the Crescent City in recent years, eager to win their share of the bounty.

One pair of brothers from New York—Abraham and Isidore Sapir (or Shapiro), alleged white slavers looking to expand their interests—seemed especially determined to shake up the status quo of Anderson County. Changing their names to Harry and Charles Parker, respectively, they came to New Orleans in the early years of the twentieth century and opened a saloon on the corner of Liberty and Customhouse Streets. In 1910, they sold that saloon and bought a dance hall on Franklin Street called the 101 Ranch, right behind Tom Anderson’s Annex. By all reports, they were not pleasant, easygoing fellows like the mayor of Storyville. And they were apparently eager to show the local vice lords just how a tenderloin was supposed to be run.

WHEN THE PARKER BROTHERS FIRST DECIDED TO get into the dance-hall business in Storyville, their prospects for success were bright.

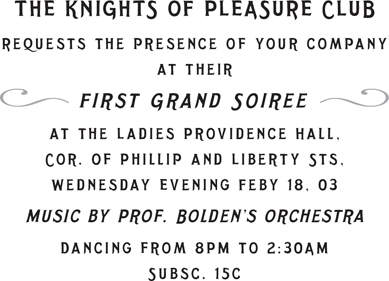

A dance craze had been sweeping the country, and bold new steps like the bunny hug, the grizzly bear, and the turkey trot were becoming wildly popular—in New Orleans as in the rest of the nation. Local clergymen and bluestockings may have complained, pointing to provisions of the Gay-Shattuck Law that were supposed to keep women, alcohol, and music strictly separated. But police enforcement had so far been lax. Business was good, and by 1910

numerous dance halls and cabarets had opened in Storyville, clustering mainly on and around Franklin Street, just one block behind the Basin Street brothels. The Parkers’ 101 Ranch quickly became one of the liveliest and most popular venues in the District, attracting crowds to hear some of the best black bands in the city.

But the Parkers weren’t satisfied. The competition for customers on Franklin Street was keen, and the brothers from New York were determined to eliminate some of their homegrown rivals.

Their first target was John “Peg” Anstedt, the popular, one-legged proprietor of Anstedt’s Saloon (a place where many white musicians like Nick LaRocca came to hear the black bands). According to local gossip, in 1911, Charles Parker began spending time with Anstedt’s mistress—a prostitute named May Gilbert—hoping to convince her to swear out an affidavit accusing her lover of being engaged in the white-slavery trade. When Anstedt heard about this, he was enraged, and responded as one typically did in Storyville in 1911—by taking a potshot at Parker one evening in a Franklin Street saloon. The bullet missed its mark, as did Parker’s retaliatory shot at Anstedt sometime later at another District dive. But although no one was hurt or arrested in the incident, it did make one thing clear—the power structure that had grown up in the District in its first decade of existence was about to be challenged.

In 1912, the Parkers sold the 101 Ranch to William Phillips, a local restaurateur (and friend of Peg Anstedt’s).

Phillips renovated the building and reopened it as the 102 Ranch, a venue that soon became a popular gathering place for the city’s horse players. Tom Anderson—still very much involved in the racing world—was said to occasionally take refuge at the 102, whenever he tired of the many tourists who came to his Annex around the corner and insisted on seeing the great host.

But the Parkers had not left the dance-hall business. That same year, in fact,

they opened the Tuxedo, almost directly across the street from the 102 Ranch—a move that was in direct violation of a clause in their sales agreement with Phillips. The new Tuxedo, moreover, was a large and modern entertainment complex, with a dime-a-dance section in the rear and a large bar up front that opened out directly onto Franklin Street. Soon the Parkers were directly competing with Phillips for the best of the city’s musical talent.

Even so, Phillips, to the Parkers’ annoyance, continued to attract a large share of the dance-hall business. The rivals argued frequently, sometimes coming to blows in the street. The resulting brawls soon created lurid newspaper headlines that ended up hurting Storyville’s reputation at a particularly inopportune time, just when reformers were looking for ammunition in their campaign to close the District.

For New Orleans’ jazzmen, however, the increasing competition among dance-hall and cabaret operators was a boon. Thanks to the ongoing dance craze—to which the revolutionary new sound proved especially conducive—jazz was becoming increasingly popular, not just with the denizens of poor black neighborhoods but among the city’s white “sporting set” as well. Work was plentiful, and musicians were finally making enough money to give up their day jobs and play full-time. Clarinetist Alphonse Picou described a typical jazzman’s schedule during these years. “

I worked at my trade all week. All day Saturday I would play in a wagon to advertise the dance that night. [Then I’d] play all night. Next morning we have to be at the depot at seven to catch the train for the lake. Play for the picnic at the lake all day. Come back and play a dance all Sunday night. Monday we advertise for the Monday night ball and play

that

Monday night. Sometimes my clarinet seemed to weigh a thousand pounds.…”

By this time, most of the now-storied venues of early New Orleans jazz were up and running. In 1910, Italian businessman Peter Ciaccio opened the Manhattan Café on Iberville. Universally known as “Pete Lala’s,” the club was, according to one Storyville denizen, “

a noisy, brawling barn of a place, [offering] music and dancing downstairs, heavy gambling in the back rooms, and assignations upstairs.” And it wasn’t long before it became central to the city’s jazz scene. “

Pete Lala’s was the headquarters,” pianist Clarence Williams would later recall, “the place where all the bands would come when they got off work, and where the girls would come to meet their main man.… They would come to drink and play and have breakfast and then go to bed.” Trombonist Kid Ory, who finally moved full-time to New Orleans in 1910, managed to get his group a regular gig at Pete Lala’s, and soon many of the other big names were playing there as well.