Empire of Sin (37 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

But respectable New Orleanians should not stand for the outrage: “In the matter of jass, New Orleans is particularly interested, since it has been widely suggested that this particular form of musical vice had its birth in this city—that it came, in fact, from doubtful surroundings in our slums. We do not recognize the honor of parenthood, but with such a story in circulation, it behooves us to be last to accept the atrocity in polite society, and where it has crept in we should make it a point of civic honor to suppress it. Its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great.”

So much, it would seem, for the music that would eventually be regarded as the first truly American art form. The

Times-Picayune

did not approve of it. Nor—judging from the

unusually large number of letters to the editor inspired by the editorial—did much of the paper’s readership; even the correspondent most sympathetic to jazz referred to it as “

a departure from the proper in music.” But the editorial’s reference to the new music as “musical vice” was telling. For the city’s privileged white elite, jazz and vice were of a piece, along with blackness generally and, for that matter, Italianness, too. All were forms of contamination—blots on the city’s escutcheon that found expression in crime, depravity, drunkenness, lewdness, corruption, and disease. These were the ills that reformers had first taken arms against almost thirty years earlier, with the lynchings at the Orleans Parish Prison. And now, in 1918, it seemed that perhaps the reformers had won. Storyville was closed, the Italian underworld was subdued, Jim Crow reigned supreme, and even jazz was under attack. Granted, the Ring was still in power, but the city seemed finally under some semblance of control. New Orleans’ thirty-year civil war, like the Great War in Europe, appeared to be nearing an end, and the city was poised to become the kind of “normal,” orderly, and businesslike place that the reformers wanted it to be.

Until, that is, the appearance of a mysterious figure with an ax in his hands.

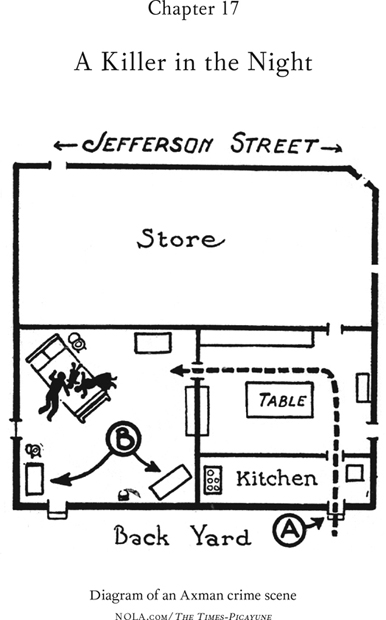

In the same manner in which Joseph Maggio and his wife, Italians, were chopped to death with a hatchet as they slept behind their grocery store at Upperline and Magnolia Streets a month ago, Louis Besumer and his wife were chopped with a hatchet early Thursday morning as they slept in their quarters back of their grocery store at Dorgenois and Laharpe Streets.

Police believe the hatchet user in both crimes was the same man.

The latest hatchet victims are in the Charity Hospital in a critical condition.

—New Orleans Times-Picayune

, June 28, 1918

FIRST THE MAGGIOS AND NOW THE BESUMERS. TWO similar crimes, two pairs of married grocers, two points on a grid that could be connected with a straight line of causality. Or not. Superintendent Frank T. Mooney couldn’t be sure. His detectives were uncertain too, though some of them clearly wanted to believe that the two events were unrelated. There were, after all, a lot of corner groceries in New Orleans, and a lot of reasons why a married couple might be brutally attacked in one of them. The two crimes didn’t

have

to be related. But it was impossible not to wonder:

Mrs. Maggio is going to sit up tonight just like Mrs. Toney

.

Certainly there were

important differences between the two attacks. For one thing, they happened on entirely different sides of the city. The Besumer assault occurred over near Esplanade Ridge, in an established, densely settled part of town; it was more than four miles away from the sparsely populated edge of Uptown, where the Maggios had been killed. And Besumer, far from being Italian, was an Eastern European Jew—a Pole, he claimed—which made no sense if the attack was Black Hand—related. That organization preyed only on other Italians. Or at least that was what Mooney’s senior detectives had always believed.

Another difference: the Besumers had actually survived their attack. They were now in Charity Hospital, both gravely injured, but Louis Besumer was expected to recover quickly. So Mooney had potential witnesses to this crime. But he hadn’t been able to get much sense from either of them in their current state. The extreme trauma of the ax attacks, which had left both victims with apparent skull fractures, had disoriented them, and they claimed to know nothing about what had happened. It might be days before they could remember any details about the attacks.

And there were no other witnesses. No one in the neighborhood had seen or heard anything—at least not until John Zanca, the driver of a bakery van, had shown up at the Besumer grocery with a delivery of bread shortly before seven on Thursday morning. Zanca had been surprised to find the grocery door closed and locked; the store was usually open at that hour. So he’d pounded on the door, and, when he got no answer there, at a side door leading to the residence behind the grocery. Finally, Zanca heard a voice inside. Someone came around to the front door and unlocked it. And when it opened, he saw Louis Besumer standing unsteadily on the threshold. The grocer was holding a damp sponge to his face and blood was streaming from a deep wound over his right eye.

“

My God,” Zanca cried. “What happened?”

Besumer said he wasn’t sure—that he was attacked in the night, but that it was nothing to worry about. Nonetheless, Zanca pushed past him into the store to reach the telephone. Besumer tried to stop him: He said that he didn’t want the police or an ambulance, that he would see a private doctor instead. But Zanca immediately telephoned the Fifth Precinct police station. “There’s been a murder or something here,” he shouted into the receiver, over Besumer’s continuing objections.

Minutes later, when police arrived and entered the residence behind the store, they found a scene in gory disarray. In the first bedroom, a sheet-less bed with bloodstained pillows stood amid piles of clothing and other effects strewn over the floor. This was apparently where Besumer had been attacked. But in the back bedroom, under a sopping sheet, they found Mrs. Harriet Besumer, unconscious and bloodied, with gaping wounds over her left ear and on the top of her head. A smudged trail of bloody footprints led from the bedroom, out through the hall, to a screened-in gallery overlooking the backyard. Here police found a hank of hair sitting in a pool of gore. Leaning against the screen nearby was a rusty ax head separated from its wooden handle.

The pair were immediately transported to Charity Hospital, where Superintendent Mooney, apparently worried that he might lose his only witnesses, rushed to question them. He found Louis Besumer conscious but dazed. The grocer—fifty-nine years old, bespectacled, and somewhat scholarly in appearance—claimed to remember nothing of the attack, or of anything at all that happened the night before.

“

I felt like I was going to faint,” he told the superintendent from his hospital bed, describing the moment he awoke, “and remember getting up and finding my wife in bed covered with blood. I put a sheet on her. I also recall having washed my face with a sponge and going to the door when the baker knocked. I found the door was not locked and that the wrong key was in the lock.”

This struck the superintendent as strange—Zanca had said that the grocery door was locked when he first tried it—and Mooney’s first suspicion was that Besumer was dissembling, that he had attacked his wife himself, perhaps cutting his own head in the struggle. That would explain his insistence that Zanca call a private physician rather than an ambulance and the police. When Mrs. Besumer regained consciousness, however, she

categorically denied that there had been a quarrel with her husband. But she could remember nothing else.

Over the next few hours, Louis Besumer became more talkative. For a man who had just been attacked with an ax, he soon grew remarkably expansive, even boastful. He was rich and well educated, he said, and he spoke many languages. Two years ago, he’d met and married Harriet Anna Lowe in Fort Lauderdale and the two had

moved to New Orleans for a rest. He’d bought the grocery store for $300 and was running it for a change of pace, almost as a hobby. His doctor, he said, had recommended that he do something like that—to buy and run a small, undemanding business—to help him recover from overwork.

“

Have you any enemies?” Mooney asked him.

“Not that I know of.”

“Any business competition?”

“Yes,” Besumer replied, “some Italian grocers. I’ve been selling things pretty cheap.”

Mooney made a note of it but didn’t pursue that line of questioning any further.

Eventually, Mrs. Besumer became more lucid as well. When Mooney asked her whether she remembered being attacked on the gallery, she paused a moment and then said she thought she did. She remembered finding someone in the grocery early that morning.

It was a mulatto man, she said, and he asked her for a package of tobacco. When she told the man that the grocery didn’t carry tobacco, he chased her. He pursued her back through the grocery, across the hall of the living quarters, to the screened-in gallery, where he struck her with an ax. That, she said, was all she remembered.

Here, finally, was something tangible to work with. Mooney alerted his detectives on the crime scene, and by afternoon they had a suspect in custody. He was Lewis Obichon, a forty-one-year-old, light-skinned black man who had apparently done a few odd jobs for Besumer earlier that week. Found at his mother’s home near the grocery, he’d been questioned about his whereabouts that morning. Obichon claimed that he’d been at the Poydras Market since one

A.M.

the night before. But when several witnesses denied this, Obichon admitted that he had lied and was evasive about why. He was arrested and taken to the Fifth Precinct station for further questioning.

But there were reasons for Mooney to doubt Mrs. Besumer’s story. Why, for instance, would Mrs. Besumer be tending the open grocery in her nightclothes? Why wouldn’t she have screamed while being pursued through the building by an ax-wielding assailant? And why would no one in the populous neighborhood have seen or heard anything at an hour when businesses up and down the street were opening for the day? All in all, Mooney was not satisfied with her account of the crime. And when he questioned Mrs. Besumer again a short time later, she turned vague and confused. No black man had attacked her, she insisted. “

If I said so formerly, I didn’t know what I was saying.”

For Mooney, of course, this was maddening. He could see the Besumer case unraveling in the same way the Maggio investigation had come apart several weeks earlier. In that case, the evidence against Andrew Maggio, the victim’s brother, had virtually evaporated under closer examination in the days after his arrest. The murder weapon that had been identified by a witness as Andrew’s razor was not, after all, the one the barber had brought home from his shop “to hone a nick from the blade”;

that

razor had subsequently been found in Andrew’s apartment, and the witness had been forced to admit his mistake. The alleged bloodstains on Andrew’s shirt, moreover, had proved to be red wine stains.

Faced with these embarrassing blunders, Mooney had been obliged to release Andrew Maggio immediately. “

The case has taken a peculiar turn,” the superintendent had announced to the press, hoping to put a better face on the fiasco. “It has become more interesting from the standpoint of investigators.… Tomorrow we will take up another phase.”

More “interesting” or not, the second phase of the Maggio investigation had yielded precisely nothing, and the case remained unsolved.

And now Mooney might have to release another man arrested on the mistaken testimony of a witness, with no alternative suspect. Hoping to put the case under tighter control, Mooney decided to deny reporters access to the confused and loose-tongued victims. But this did little to quiet the

rampant speculation in the press.

MYSTERY GROWS IN ORLEANS AX CASE

, the

States

reported after a few days of fruitless investigation. The

Item’

s headline was more probing:

MOTIVE OF AX MYSTERY PUZZLES POLICE: WHAT WAS BEHIND OUTRAGE? WHO DID IT?

By the weekend, the case had taken another bizarre turn. “

My husband is a German,” Mrs. Besumer blurted during one of her rambling monologues. “He claims he is not. I don’t know where he got the money to buy his store.” In July of 1918, with the United States actively at war with the Germans in Europe, this was an electrifying revelation, full of insidious possibilities. And when police turned up several suitcases in the Besumer home stuffed with hundreds of letters and pamphlets in Russian, Yiddish, and German, speculation rose to new heights.

SPY PLOT MAY BE AT BOTTOM OF AX MYSTERY

, the

Item

announced. Stories were soon circulating about hidden code books, suspiciously expensive clothing, and a foot locker fitted with a homemade secret compartment. If Besumer was indeed a German spy, the

Item

wondered, could this explain the violence that had occurred on Thursday morning? “Did the woman discover Besumer’s supposed German connections and attack him? Did he have cause to distrust her loyalty and attack

her

?… Did the two have a fearful silent struggle on the gallery?”