Empire of Sin (4 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

The result was a city that had become hopelessly backward, at least in terms of urban development. Other major cities—New York, Chicago, St. Louis—had surged ahead with electrified streetcars, modern sanitation facilities, and miles and miles of well-paved streets. But New Orleans seemed stuck in an earlier era: streetcars were still pulled by dusty, overworked mules; sewage ran through open gutters at the edges of dirt-paved or otherwise primitive streets; few residents had running water; and the city’s main arteries—except for the recently electrified main drag of Canal Street—were still illuminated by old-fashioned gas lamps. (New Orleans, it was often observed, was the first American metropolis to build an opera house, but the last to build a sewerage system.) By the late 1880s, then,

the city desperately needed to rebuild its port and overhaul its increasingly antiquated infrastructure. To do all of that, it urgently needed to attract Northern capital investment. But as one local businessman wrote, “

The reputation of our city has been fearful and it has been utterly impossible to interest capital in any enterprise in New Orleans.”

Faced with this rapidly deteriorating situation, the Crescent City’s self-anointed leading citizens had by 1888 concluded that drastic measures were necessary to halt the city’s moral and economic slide. In that year, a well-heeled young lawyer named William S. Parkerson formed a new political party, the Young Men’s Democratic Association, with the explicit purpose of taking on the Ring machine that had allowed such conditions to flourish in the city. Other similar parties, of course, had risen up with that same goal in the past, only to falter after a few years of limited electoral success. But Parkerson’s YMDA had some very powerful supporters. “

Its campaign committee,” as one historian put it, “read like a blue book of the city’s commercial elite,” and they were all determined to put the city on the road to long-desired reform. Rejecting the candidates put up by Democratic Party regulars in the spring city elections (“

a ticket which is an insult to the intelligence of this community and a menace to its progress and integrity”), the YMDA instead rallied around its own slate of higher-toned hopefuls. Led by mayoral candidate Joseph A. Shakspeare, the YMDA ticket promised the voters a war on vice and corruption, a total revamping of the city’s inept and venal police department, and a large-scale effort to revitalize the crumbling infrastructure through honest tax collection and other sound business practices. And the reformers backed these heady promises with a threat that their opponents could understand: the association was gathering an arsenal, and would ensure that the election was conducted properly “

if need be at the point of the bayonet.”

The strong-arm tactics worked. Though Ring operatives attempted “

countless questionable devices and election legerdemain” to steal the vote, armed contingents of YMDA men at every polling station kept the usual hired thugs and vote buyers in check. And when the votes were counted, Shakspeare had won a commanding victory, with the rest of the reform slate taking all but two of the city’s seventeen wards. The triumphant Parkerson, offered the position of city attorney in Shakspeare’s new administration, ultimately declined to serve. But he—along with his gun-toting private militia—would remain a potent force backing the new mayor in all of his endeavors to come.

For the cream of New Orleans society, this was a hopeful beginning. At least for the time being, the so-called better half—the city’s clergymen and newspaper editors, its upright lawyers and businessmen, its social reformers and club women—would control city government, with a popular mandate for change that few could gainsay. But the job before them was clear: in order to survive and thrive in the coming new century, the city of New Orleans—like brothel madam Josie Lobrano—was going to have to remake itself along more respectable lines. The city would have to normalize its scandalous sex life, isolate and regulate its notorious entertainment districts, and take control of the infamous crime on its streets. The task would be formidable, requiring direct confrontation with the forces of the city’s demimonde, its entrenched vice industries, and its black and immigrant underworlds. To win their city back, in other words, the self-styled champions of respectability and order were going to have to launch the equivalent of an all-out civil war.

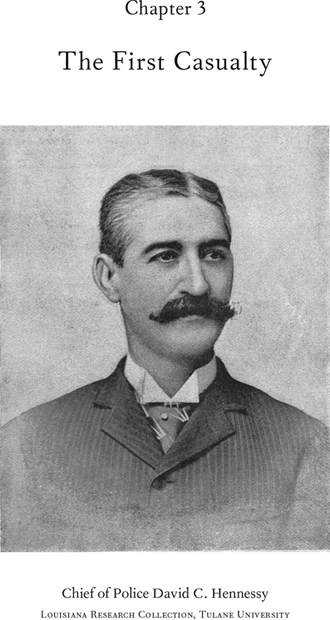

That the first major casualty in this war was the city’s popular police chief—David Hennessy, gunned down in front of his own home—was an early indication of just how bitterly the conflict was going to be fought.

THE WAR BEGAN QUIETLY ENOUGH, ON A CHILLY, WET evening in October of 1890.

At the weekly police board meeting at City Hall, New Orleans mayor Joseph A. Shakspeare was presiding over

the disciplinary hearing of two police officers accused of blackmail. Beside him at the examiner’s table sat the other four members of the police board, along with several clerks and Superintendent and Chief of Police David C. Hennessy. Rain pattered the tall windows of the boardroom as the last of the early-evening light faded away.

Sgt. James Lynch and Stableman H. Thibodaux—both officers from the Eighth Precinct, just across the river in Algiers—stood in front of the board, listening to the charges against them. The pair had been accused of extorting bribes from several grocery-saloons on a Sunday evening ten days earlier. The officers had allegedly gone from one establishment to another in Algiers, demanding drinks; then, when they were served, they would turn around and threaten to charge the owners with a violation of the city’s putatively faith-based Sunday Closing Law unless they paid an adequate bribe. Four of their victims had felt outraged enough to file complaints with the police department.

Sergeant Lynch, asked to respond to the charges, pled not guilty, and requested that the hearing be postponed to allow him and Thibodaux to prepare a defense.

But Shakspeare wouldn’t hear of it. The mayor pointed out that the witnesses had been put to substantial trouble coming over on the ferry from Algiers on such a rainy evening. The board would therefore hear their testimony that night. The accused could answer the charges at a later date.

Shakspeare, now more than two years into his term, was doubtless feeling somewhat outraged himself. The law forbidding Sunday liquor sales was one of his own pet initiatives, and to see it abused by the city’s own police must have been particularly galling. Reforming the police department, after all, had been one of the major planks in the platform on which he’d been elected back in 1888.

Virtually his first act as mayor had been to appoint his friend Hennessy as chief, instructing him to reorganize the entire department and get rid of the corrupt elements that had plagued it for decades. The accusations against Lynch and Thibodaux, unfortunately, showed just how much remained to be done.

Not that anyone was blaming the chief of police for the lingering problems. David C. Hennessy—

tall, lean, and dourly handsome, sporting the ubiquitous shapely mustache of 1890s fashion—was one of the most popular and admired figures in the Crescent City. Hired as a police messenger while still a boy—after his father, a longtime metro policeman, was killed in a barroom gunfight—he’d been a lawman all his life. His selection as

the country’s youngest police chief had been widely applauded at the time, particularly by the reform-minded element that had swept Shakspeare and his allies into office. True, Hennessy had detractors. As a young man, he had once shot and killed a rival detective on the street, and there were some who still claimed that the shooting was unprovoked. But the incident had ultimately been ruled a killing in self-defense and all charges against Hennessy had subsequently been dropped. Now, at thirty-two years of age, he was regarded by many as the straightest of straight arrows. According to the local papers, Hennessy didn’t drink, he didn’t gamble, and he even avoided fraternizing with women—except for his widowed mother, with whom he lived in a modest cottage on Girod Street. He was also a deeply religious man, stopping at the Jesuit church every evening at six to pray. He was seen by most reformers, in short, as a man of unimpeachable honesty and character—just the person they needed to reinvigorate the police department and start cleaning up the vice- and crime-ridden place their city had become.

But as the testimony of the four witnesses was making painfully obvious, progress had been slow. One of the alleged victims, an Italian grocer named Philip Geraci, described the two officers entering his shop at seven

P.M.

and demanding cash from the till. Apparently, this was not the first confrontation between them. “

You had threatened me before,” Geraci said, addressing Officer Thibodaux. “[You] had cursed me and called me a ‘dirty Dago.’ Everybody knows you are a bulldozer and a tough, and I was never in trouble until you forced me into it!”

Shakspeare clearly found this story plausible enough, and when the other witnesses’ testimony proved just as damning, the mayor decided that he’d heard all he needed to hear. He, Hennessy, and the rest of the board agreed that the evidence of extortion was irrefutable. And so—with the self-righteous peremptoriness that was to characterize the reformers’ efforts for decades to come—they decided to dismiss the two officers on the spot, without waiting to hear their defense. Why bother with the niceties of judicial process, after all, when there was an entire city to clean up?

After the police board meeting adjourned, the chief and another officer—Capt. William “Billy” O’Connor of the Boylan private detective agency—sat in Hennessy’s office at the Central Police Station, chatting idly for an hour before heading home for the night. O’Connor was the chief’s old friend, a former colleague who could often be found in Hennessy’s company around town. But tonight he was

accompanying his friend on a semiofficial basis: O’Connor was acting as the chief’s bodyguard for the evening. After several anonymous threats to Hennessy’s life over the past few months, the city had arranged with the Boylan agency to provide the chief with round-the-clock protection. And though Hennessy himself regarded this precaution as unnecessary, Mayor Shakspeare had insisted upon it. The fact that the job had gone to the private Boylan agency indicated how much confidence the mayor put in his own police department.

The death threats had stemmed from an ongoing investigation that the chief was conducting into the city’s Italian underworld. For some time now, New Orleans’ Italian community had been

roiled by a struggle between two rival families for the lucrative dockworker contracts on the city’s downriver wharves. The Provenzanos, who originally had the contracts with the city’s fruit importers, and the Matrangas, who eventually wrested them away, forcing the Provenzanos out of business, had been feuding violently. The resulting wave of back-alley shootings and stabbings had outraged the city’s business community, who cited it as just the kind of nonsense that was scaring away investment from Northern capitalists. After several violent murders of alleged Provenzano and Matranga associates in late 1888 and early 1889, Hennessy had decided to take action.

Inviting representatives of both clans to the Red Light Club on Customhouse Street, he all but forced them to shake hands in truce, warning them that the city would no longer tolerate their feuds. The perpetrator of any crime in the Italian community, Hennessy warned, would henceforth be hunted down and prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

But the truce ended up lasting for less than a year. On the night of May 5, 1890, the Matranga brothers and five of their workers were returning home after a long day’s work on the docks when their horse-drawn wagon was ambushed by gunmen on Esplanade Avenue. Several men were injured, including family patriarch Antonio Matranga himself, who eventually lost a leg as a result of his injuries. Six Provenzano men were accused of the attack and subsequently tried. And although the six were convicted, Chief Hennessy was dissatisfied with the verdict. Convinced that the shooting victims had perjured themselves at the trial,

he launched an investigation into the Matranga organization, even sending to Italy for information that might tie the family to alleged Mafia crime figures in Sicily. Exactly what Hennessy had turned up in his research was never made public, but it was apparently damning enough to convince a judge to vacate the Provenzano convictions and order a new trial—and to mark the chief himself, scheduled to testify in the retrial, as a rumored target for assassination.

But

on this rainy Wednesday night in October, just two days before the scheduled start of the Provenzano retrial, Hennessy seemed anything but worried about his safety. “The chief was in the best of spirits,” O’Connor would later recall to reporters. And as the two men left the police station at a few minutes after eleven, the chief was even feeling sociable enough to invite his bodyguard into Dominic Verget’s saloon to share a dozen oysters (which Hennessy, the famous teetotaler, washed down with a small glass of milk).

The driving rain had all but stopped by the time they left Verget’s. A drizzly mist now crept along the gleaming streets, muffling the men’s footsteps as they walked up Rampart. At the corner of Girod, just a few blocks from the chief’s house, they stopped.