Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (28 page)

Read Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 Online

Authors: John H. Elliott

Tags: #Amazon.com, #European History

BOOK: Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830

11.22Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The incorporation of the Indies into the Crown of Castile had immense longterm consequences for the development of Spanish America. Technically this was to be a Castilian, rather than a Spanish, America, just as the territories of North America settled from the British Isles were technically to constitute an English, rather than a British, America. Although the kings of Castile were also kings of Aragon, and a number of Aragonese participated in the first stages of Spanish expansion into the New World,18 there was to be a lingering uncertainty over the rights of natives of the Crown of Aragon to move to, and settle in, America. The sixteenth-century legal texts relating to the exclusion of foreigners from the Indies appeared then, as now, ambiguous and contradictory over the exact status of possible immigrants from Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia. In practice it seems that there were no serious impediments to their securing a licence to emigrate to the Indies, but, for geographical and other reasons, those who took advantage of the opportunity turned out to be relatively few19

Much more immediately significant was the endowment of the new American territories with laws and institutions modelled on those of Castile rather than of Aragon. Although there was a strong tradition in medieval Castile, as in the Crown of Aragon, of a contractual relationship between monarch and subjects, and this had penetrated deep into Castilian political culture,20 Castile emerged from the Middle Ages with weaker theoretical and institutional barriers against the authoritarian exercise of kingship than those to be found in the Aragonese realms. Fifteenth-century Castilian jurists in the service of the crown had argued for a `royal absolute power' (poderio real absoluto), which gave wide latitude to the royal prerogative. The sixteenth-century rulers of Castile inherited this useful formula, which could obviously be used to override the crown's contractual obligations in real or alleged emergencies.21 While the moral restraints on Castilian kingship remained strong, the potential for the authoritarian exercise of power was now established; and Charles V's suppression of the Comunero revolt in 1521 would effectively reduce still further the chances of imposing effective institutional restraints in a realm whose representative assembly, the Cortes of Castile, suffered from a number of grave, if not necessarily fatal, weaknesses.

With the Indies juridically incorporated into the Castilian crown as a conquered territory, the monarchs in principle were free to govern them as they liked. One institution that they were in no hurry to see transferred to the other side of the Atlantic was a representative assembly, or Cortes, on the Castilian, and still less on the Aragonese, model. The settlers themselves might petition for such assemblies, and viceroys and even the crown itself might occasionally play with the idea of introducing them, but the disadvantages were always held to outweigh the advantages, and the American territories never acquired Cortes of their own.22

Yet although the Indies were seen as a Castilian conquest, and were therefore united to the Castilian crown by what was known as an `accessory' union rather than on a basis of equality, aeque principaliter, the fact remained that the conquerors themselves were the king's own Castilian subjects, and were evolving into pobladores, or settlers, although proudly clinging to their title of conquistadores. As conquerors, they understandably expected their services to be properly remembered and rewarded by a grateful monarch, who could hardly deny them and their descendants the kind of rights which men of their worth would expect to enjoy in Castile. Such a recognition might not extend to the formal establishment of a Cortes, but this did not preclude the development of other institutional devices and forums, notably the cabildo or town council, for expressing collective grievances. Moreover, it was clear that the status of the lands that their valour had brought under Castilian rule should receive some proper acknowledgement. The conquerors had overthrown the empires of the Aztecs and the Incas, and had dispossessed great rulers. In the circumstances, it was natural that the larger preconquest political entities which they had delivered into the hands of their monarch should have a comparable standing to that of the various realms - Leon, Toledo, Cordoba, Murcia, Jaen, Seville and, most recently, Granada - which constituted the Crown of Castile.23 New Spain, New Granada, Quito and Peru would all therefore come to be known as kingdoms, and the conquerors and their descendants expected them to be ruled in a manner appropriate to their status.

While the crown was well aware of the dangers of unnecessarily bruising the susceptibilities of the conquistadores, especially in the early stages of settlement when the political and military situation remained very volatile, it was determined to impose its own authority at the earliest opportunity. Too much was at stake, in terms of both potential American revenues and the commitment entered into with the papacy for the salvation of Indian souls, to permit the kind of laissez-faire approach that would characterize so much of early Stuart policy towards the new plantations. Imbued with a high sense of their own authority, which they had fought so hard to assert in the Iberian peninsula itself, Ferdinand and Isabella moved with speed to meet the obligations incumbent on them as `natural lords' of the Indies, while at the same time maximizing the potential to the crown of its new territorial acquisitions.

This required the rapid development and imposition on the Indies of administrative, judicial and ecclesiastical structures - a process that would be carried forward by Charles V and Philip II. From the first, expeditions of conquest had been accompanied by royal officials whose task was to watch over the crown's interests, and particularly its interests in the sharing out of the spoils. As an incorporated territory the Indies fell within the orbit of the supreme governing body of Castile, the Council of Castile, and in the early years the monarchs would turn for advice on Indies affairs to selected members of the council, and in particular to the Archdeacon of Seville and eventual Bishop of Burgos, Juan Rodriguez de Fonseca, who was effectively the supremo in the management of the Indies trade and the administration of the Indies from 1493 for almost the entire period down to his death in 1524.24 By 1517 this small group of councillors was being spoken of as ,the Council of the Indies',25 and in 1523 this became a formalized and distinctive Council within the conciliar structure of the Spanish Monarchy.26

The newly constituted Council of the Indies, with Fonseca as its first president, was to have the prime responsibility for government, trade, defence and the administration of justice in Spanish America throughout the nearly two centuries of Habsburg rule. Spain thus acquired at an early stage of its imperial enterprise a central organ for the formulation and implementation of policy relating to every aspect of the life of its American possessions. Had Charles I's regime survived, Archbishop Laud's Commission for Regulating Plantations might conceivably have evolved into a broadly similar omnicompetent body. As it was, it would take time, and various experiments, for an even remotely equivalent body - the Board of Trade of 1696 - to be established in England, and even then, as its name suggests, its primary concern was with the commercial aspects of the relationship between the mother country and its American colonies.

The immediate and most pressing task of the councillors of the Indies, following Cortes's conquest of Mexico between 1519 and 1521, was to ensure that it should be followed as quickly as possible by a second conquest - that of the conquerors by the crown. In the early years of the century the crown had fought tenaciously to strip Columbus and his heirs of what quickly came to be seen as the excessive powers and privileges granted to him under the terms of his original `capitulations' with the Catholic Monarchs. With vast riches from the conquered empire of Montezuma in prospect, it was essential that Cortes, who in 1522 had been appointed governor, captain-general and Justicia Mayor of New Spain by a grateful monarch in recognition both of his services and of the realities of Mexico in the immediate aftermath of conquest, should have his wings clipped as those of Columbus had been clipped before him. As the bureaucrats descended on New Spain, the conqueror saw himself stripped of his administrative functions and subjected to a residencia - the normal form of judicial inquiry into the activities of servants of the crown against whom complaints had been lodged. Simultaneously harried and honoured - he received the title of marquis and the grant of substantial lands with 23,000 Indian vassals for his services - he eventually abandoned the struggle and left for Spain in 1539, never to return. Francisco Pizarro, too, was to be simultaneously rewarded with the title of marquis and harassed by treasury officials, and was on the verge of losing his governorship of Peru when he was assassinated by his disappointed rivals in 1541.27

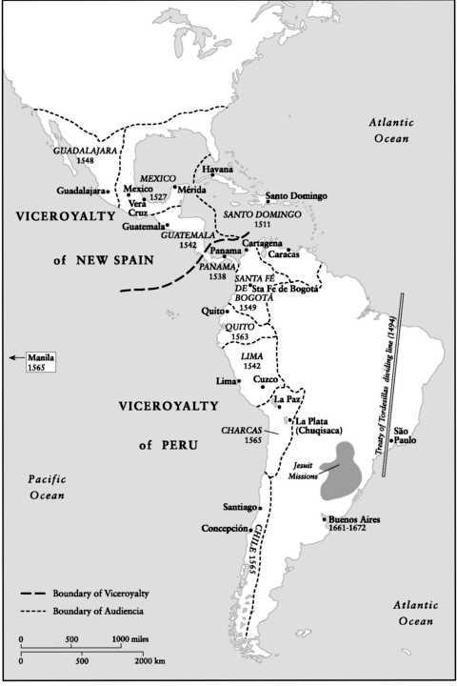

While the conquistadores and the encomenderos were to be dispossessed as quickly as possible of effective powers of government, it was essential to create an administrative apparatus to fill the vacuum. To achieve this, the crown made use of institutions which had been tried and tested at home, and were now pragmatically adapted to meet American needs. The first Audiencia, or high court, in the New World had been established in Santo Domingo in 1511. As more and more mainland territory came under Spanish rule, so more Audiencias were set up: the Audiencia of New Spain in 1530, following a false start three years earlier; of Panama in 1538; of Peru and Guatemala, both in 1543, and of Guadalajara (New Galicia) and Santa Fe de Bogota in 1547. By the end of the century there were ten American Audiencias.28 As a judicial tribunal the Audiencia was modelled on the chancelleries or Audiencias of Valladolid and Granada, but, unlike its counterparts in the Crown of Castile, it would develop administrative as well as judicial functions, as an extension of its obligation to maintain a judicial oversight over all administrative activities in territories far removed from the physical presence of the monarch.

These administrative activities were initially carried out by governors (gobernadores), a title conferred on a number of the early conquistadores. Governorships proved to be particularly useful for the administration and defence of outlying regions, and 35 such provincial governorships existed at one time or another during the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.29 But the supreme ruling institution over large parts of Spain's empire of the Indies was to be the viceroyalty. This had originally been developed for the government of the medieval Catalan-Aragonese empire in the Mediterranean, and the appointment of Columbus in 1492 as viceroy and governor-general of any lands he discovered may have been modelled on the example of the government of Sardinia.30 As a result of his failures in the government of Hispaniola Columbus was stripped of his viceregal title in 1499, and the viceroyalty went into temporary abeyance in the New World as the crown chose instead to appoint governors, captain-generals and adelantados (the title given to the men put in charge of newly conquered frontier regions during the reconquest of southern Spain from the Moors).

Map 3. Spanish American Viceroyalties and Audiencias (sixteenth and seventeenth centuries).

Based on Francisco Morales Padron, Historia general de America (1975), vol. VI, p. 391.

The conquest of Mexico, however, posed problems of administration on a scale hitherto unprecedented in the Indies. The government of New Spain between 1528 and 1530 by its first Audiencia proved a disaster, with the judges and the conquistadores at each other's throats. Although the new Audiencia appointed in 1530 represented a marked improvement in terms of the quality of government, it was clear that a new and better solution had to be found. In 1535 Don Antonio de Mendoza, the younger son of a prominent Castilian noble house, was appointed first viceroy of New Spain, and held the post with distinction for sixteen years (a length of tenure which would never be equalled, as the viceregal system consolidated itself, and tenures of six to eight years became the norm).

Mendoza's success encouraged the Council of the Indies to repeat the experiment in Peru, which was transformed into a viceroyalty in 1542. New Spain and Peru were to remain the sole American viceroyalties until the elevation in the eighteenth century of New Granada, with its capital in Santa Fe de Bogota, and the region of Rio de la Plata, with its capital in Buenos Aires, to the rank of viceroyalties. In the words of the legislation of 1542, `the kingdoms of New Spain and Peru are to be ruled and governed by viceroys, who shall represent our royal person, hold the superior government, do and administer justice equally to all our subjects and vassals, and concern themselves with everything that will promote the calm, peace, ennoblement and pacification of those provinces ...'31

In effect, therefore, the viceroy was to be the alter ego of a necessarily absentee ruler, and the living mirror of kingship in a distant land. Generally drawn from one or other of the great noble houses of Spain, a viceroy crossed the Atlantic - as befitted his rank - accompanied by a large entourage of family members and servants, all anxious for rich pickings in the New World during his tenure of office. His arrival on American soil, and his passage through his territory to the capital city, was as carefully staged a ritual event as if the king himself were taking possession of his realm. Each new viceroy of New Spain would follow the route to the capital taken by Hernan Cortes. On arrival at the port of Vera Cruz, he would be ceremonially received by the civil and military authorities, and spend a few days in formal duties, like inspecting the fortifications, before setting out on his triumphal progress towards Mexico City. Moving inland by slow stages, he would be greeted in towns and villages along the route by ceremonial arches, decorated streets, singing and dancing Indians, and effusive orations by Spanish and Indian officials. Arriving at the Indian city of Tlaxcala, which had loyally supported Cortes during the conquest of Mexico, he would make a ceremonial entry on horseback, preceded by the indigenous nobility, and followed by vast crowds of Indians to the accompaniment of drums and music. Having thus symbolically recognized the indigenous contribution to the conquest, and enjoyed or endured three days of festivities, he continued on his progress to the creole city of Puebla, to pay a comparable tribute to the Spanish conquerors. Here he spent eight days before moving on to Otumba, the site of Cortes's first victory after the retreat from Tenochtitlan. At Otumba he would be met by the outgoing viceroy, who, in a symbolic transfer of authority, presented him with the baton of command. The triumphal progress, part Roman triumph, part Renaissance royal entry, culminated in Mexico City itself, where the ceremonial arches were more elaborate, the festivities more lavish, the rejoicings more tumultuous, than anywhere else along the route.32

Other books

Magic and Mayhem: Witch and Were (Kindle Worlds Novella) by Eliza Gayle

Faith’s Temptation (Dueling Dragons MC Book 1) by Angie Sakai

Seduce Me by Jo Leigh

Cat and Company by Tracy Cooper-Posey

Waiting for Mr. Darcy by Chamein Canton

To Refuse Such a Man: A Pride and Prejudice Variation by P. O. Dixon

Elizabeth Is Missing by Emma Healey

Dorian's Destiny: Altered by Amanda Long

The Emancipation of Robert Sadler by Robert Sadler, Marie Chapian