Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (3 page)

Read Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 Online

Authors: John H. Elliott

Tags: #Amazon.com, #European History

BOOK: Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830

5.58Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The idea for this book first came to me at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, at a moment when I felt that the time had come to move away from the history of Habsbsurg Spain and Europe, and take a harder look at Spain's interaction with its overseas possessions. As I had by then spent almost seventeen years in the United States, there seemed to me a certain logic in looking at colonial Spanish America in a context that would span the Atlantic and allow me to draw parallels between the American experiences of Spaniards and Britons. I am deeply indebted to colleagues and visiting members at the Institute who encouraged and assisted my first steps towards a survey of the two colonial empires, and also to friends and colleagues in the History Department of Princeton University. In particular I owe a debt of gratitude of Professors Stephen Innes and William B. Taylor, both of them former visiting members of the Institute, who invited me to the University of Virginia in 1989 to try out some of my early ideas in a series of seminars.

My return to England in 1990 to the Regius Chair of Modern History in Oxford meant that I largely had to put the project to one side for seven years, but I am grateful for a series of lecture invitations that enabled me to keep the idea alive and to develop some of the themes that have found a place in this book. Among these were the Becker Lectures at Cornell University in 1992, the Stenton Lecture at the University of Reading in 1993, and in 1994 the Radcliffe Lectures at the University of Warwick, a pioneer in the development of Comparative American studies in this country under the expert guidance of Professors Alistair Hennessy and Anthony McFarlane. I have also at various times benefited from careful and perceptive criticisms of individual lectures or articles by colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic, including Timothy Breen, Nicholas Canny, Jack Greene, John Murrin, Mary Beth Norton, Anthony Pagden and Michael Zuckerman. Josep Fradera of the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, and Manuel Lucena Giraldo of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas in Madrid have been generous with their suggestions and advice on recent publications.

In Oxford itself, I learnt much from two of my graduate students, Kenneth Mills and Cayetana Alvarez de Toledo, working respectively on the histories of colonial Peru and New Spain. Retirement allowed me at last to settle down to the writing of the book, a task made much easier by the accessibility of the splendid Vere Harmsworth Library in Oxford's new Rothermere American Institute. As the work approached completion the visiting Harmsworth Professor of American History at Oxford for 2003-4, Professor Richard Beeman of the University of Pennsylvania, very generously offered to read through my draft text. I am enormously grateful to him for the close scrutiny he gave it, and for his numerous suggestions for its improvement, which I have done my best to follow

Edmund Morgan and David Weber commented generously on the text when it had reached its nearly final form, and I have also benefited from the comments of Jonathan Brown and Peter Bakewell on individual sections. At a late stage in the proceedings Philip Morgan devoted much time and thought to preparing a detailed list of suggestions and further references. While it was impossible to follow them all up in the time available to me, his suggestions have enriched the book, and have enabled me to see in a new light some of the questions I have sought to address.

In the final stages of the preparation of the book I am much indebted to SarahJane White, who gave generously of her time to put the bibliography into shape. I am grateful, too, to Bernard Dod and Rosamund Howe for their copy-editing, to Meg Davis for preparing the index and to Julia Ruxton for her indefatigable efforts in tracking down and securing the illustrations I suggested. At Yale University Press Robert Baldock has taken a close personal interest in the progress of the work, and has been consistently supportive, resourceful and encouraging. I am deeply grateful to him and his team, and in particular to Candida Brazil and Stephen Kent, for all they have done to move the book speedily and efficiently through the various stages of production and to ensure its emergence in such a handsome form. Fortunate the author who can count on such support.

Oriel College, Oxford

7 November 2005

Note on the Text

Spelling, punctuation and capitalization of English and Spanish texts of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries have normally been modernized, except in a number of instances where it seemed desirable to retain them in their original form.

The names of Spanish monarchs have been anglicized, with the exception of Charles II of Spain, who appears as Carlos II in order to avoid confusion with the contemporaneous Charles II of England.

PART 1

Occupation

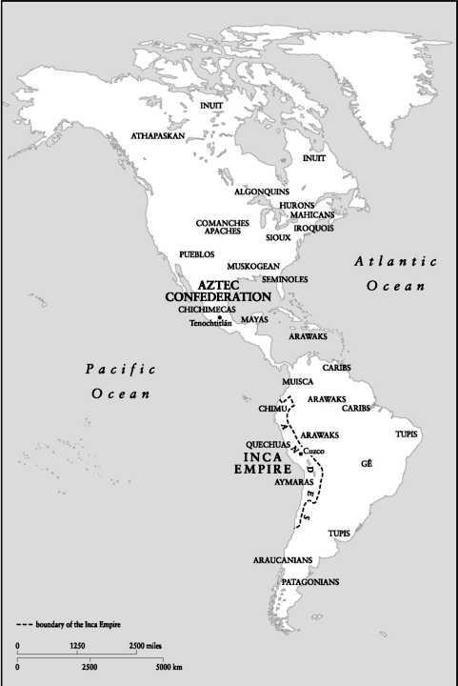

Map 1. The Peoples of America, 1492.

Based on Pierre Chaunu, L'Amerique et les Ameriques (Paris 1964), map. 3.

CHAPTER 1

Intrusion and Empire

Hernan Cortes and Christopher Newport

A shrewd notary from Extremadura, turned colonist and adventurer, and a onearmed ex-privateer from Limehouse, in the county of Middlesex. Eighty-seven years separate the expeditions, led by Hernan Cortes and Captain Christopher Newport respectively, that laid the foundations of the empires of Spain and Britain on the mainland of America. The first, consisting of ten ships, set sail from Cuba on 18 February 1519. The second, of only three ships, left London on 29 December 1606, although the sailing date was the 19th for Captain Newport and his men, who still reckoned by the Julian calendar. That the English persisted in using a calendar abandoned by Spain and much of the continent in 1582 was a small but telling indication of the comprehensive character of the change that had overtaken Europe during the course of those eighty-seven years. The Lutheran Reformation, which was already brewing when Cortes made his precipitate departure from Cuba, unleashed the forces that were to divide Christendom into warring religious camps. The decision of the England of Elizabeth to cling to the old reckoning rather than accept the new Gregorian calendar emanating from the seat of the anti-Christ in Rome suggests that - in spite of the assumptions of later historians - Protestantism and modernity were not invariably synonymous.'

After reconnoitring the coastline of Yucatan, Cortes, whose ships were lying off the island which the Spaniards called San Juan de U16a, set off in his boats on 22 April 1519 for the Mexican mainland with some 200 of his 530 men.2 Once ashore, the intruders were well received by the local Totonac inhabitants before being formally greeted by a chieftain who explained that he governed the province on behalf of a great emperor, Montezuma, to whom the news of the arrival of these strange bearded white men was hastily sent. During the following weeks, while waiting for a reply from Montezuma, Cortes reconnoitred the coastal region, discovered that there were deep divisions in Montezuma's Mexica empire, and, in a duly notarized ceremony, formally took possession of the country, including the land yet to be explored, in the name of Charles, King of Spain.' In this he was following the instructions of his immediate superior, Diego Velazquez, the governor of Cuba, who had ordered that `in all the islands that are discovered, you should leap on shore in the presence of your scribe and many witnesses, and in the name of their Highnesses take and assume possession of them with all possible solemnity 4

In other respects, however, Cortes, the protege and one-time secretary of Velazquez, proved considerably less faithful to his instructions. The governor of Cuba had specifically ordered that the expedition was to be an expedition for trade and exploration. He did not authorize Cortes to conquer or to settle.' Velazquez's purpose was to keep his own interests alive while seeking formal authorization from Spain to establish a settlement on the mainland under his own jurisdiction, but Cortes and his confidants had other ideas. Cortes's intention from the first had been to poblar - to settle any lands that he should discover - and this could be done only by defying his superior and securing his own authorization from the crown. This he now proceeded to do in a series of brilliant manoeuvres. By the laws of medieval Castile the community could, in certain circumstances, take collective action against a `tyrannical' monarch or minister. Cortes's expeditionary force now reconstituted itself as a formal community, by incorporating itself on 28 June 1519 as a town, to be known as Villa Rica de Vera Cruz, which the Spaniards promptly started to lay out and build. The new municipality, acting in the name of the king in place of his `tyrannical' governor of Cuba, whose authority it rejected, then appointed Cortes as its mayor (alcalde mayor) and captain of the royal army. By this manoeuvre, Cortes was freed from his obligations to the `tyrant' Velazquez. Thereafter, following the king's best interests, he could lead his men inland to conquer the empire of Montezuma, and transform nominal possession into real possession of the land.6

Initially the plan succeeded better than Cortes could have dared to hope, although its final realization was to be attended by terrible trials and tribulations for the Spaniards, and by vast losses of life among the Mesoamerican population. On 8 August he and some three hundred of his men set off on their march into the interior, in a bid to reach Montezuma in his lake-encircled city of Tenochtitlan (fig. 1). As they moved inland, they threw down `idols' and set up crosses in Indian places of worship, skirmished, fought and manoeuvred their way through difficult, mountainous country, and picked up a host of Mesoamerican allies, who were chafing under the dominion of the Mexica. On 8 November, Cortes and his men began slowly moving down the long causeway that linked the lakeshore to the city, `marching with great difficulty', according to the account written many years later by his secretary and chaplain, Francisco Lopez de Gomara, `because of the pressure of the crowds that came out to see them'. As they drew closer, they found `4,000 gentlemen of the court ... waiting to receive them', until finally, as they approached the wooden drawbridge, the Emperor Montezuma himself came forward to greet them, walking under `a pallium of gold and green feathers, strung about with silver hangings, and carried by four gentlemen (fig. 2)'.'

It was an extraordinary moment, this moment of encounter between the representatives of two civilizations hitherto unknown to each other: Montezuma II, outwardly impassive but inwardly troubled, the `emperor' of the Nahuatl-speaking Mexica, who had settled on their lake island in the fertile valley of Mexico around 1345, and had emerged after a series of ruthless and bloody campaigns as the head of a confederation, the Triple Alliance, that had come to dominate central Mexico; and the astute and devious Hernan Cortes, the self-appointed champion of a King of Spain who, four months earlier, had been elected Holy Roman Emperor, under the name of Charles V, and was now, at least nominally, the most powerful sovereign in Renaissance Europe.

The problem of mutual comprehension made itself felt immediately. Cortes, in Gomara's words, `dismounted and approached Montezuma to embrace him in the Spanish fashion, but was prevented by those who were supporting him, for it was a sin to touch him'. Taking off a necklace of pearls and cut glass that he was wearing, Cortes did, however, manage to place it around Montezuma's neck. The gift seems to have given Montezuma pleasure, and was reciprocated with two necklaces, each hung with eight gold shrimps. They were now entering the city, where Montezuma placed at the disposal of the Spaniards the splendid palace that had once belonged to his father.

After Cortes and his men had rested, Montezuma returned with more gifts, and then made a speech of welcome in which, as reported by Cortes, he identified the Spaniards as descendants of a great lord who had been expelled from the land of the Nahuas and were now returning to claim their own. He therefore submitted himself and his people to the King of Spain, as their `natural lord'. This 'voluntary' surrender of sovereignty, which is likely to have been no more than a Spanish interpretation, or deliberate misinterpretation, of characteristically elaborate Nahuatl expressions of courtesy and welcome, was to be followed by a further, and more formal, act of submission a few days later, after Cortes, with typical boldness, had seized Montezuma and taken him into custody.'

Cortes had secured what he wanted: a translatio imperii, a transfer of empire, from Montezuma to his own master, the Emperor Charles V. In Spanish eyes this transfer of empire gave Charles legitimate authority over the land and dominions of the Mexica. It thus justified the subsequent actions of the Spaniards, who, after being forced by an uprising in the city to fight their way out of Tenochtitlan under cover of darkness, spent the next fourteen months fighting to recover what they regarded as properly theirs. With the fall of Tenochtitlan in August 1521 after a bitter siege, the Mexica empire was effectively destroyed. Mexico had become, in fact as well as theory, a possession of the Crown of Castile, and in due course was to be transformed into Spain's first American viceroyalty, the viceroyalty of New Spain.

Other books

For Sale —American Paradise by Willie Drye

Rebecca Stubbs: The Vicar's Daughter by Hannah Buckland

What She Left: Enhanced Edition by T. R. Richmond

Ghostly Realm - Not Even Death Could Separate Them by Kelley, Cindy J.

See How They Run by Tom Bale

El tango de la Guardia Vieja by Arturo Pérez-Reverte

Coming Home by Rosamunde Pilcher

Tales of the Wold Newton Universe by Philip José Farmer

Capturing Paris by Katharine Davis