Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (75 page)

Read Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 Online

Authors: John H. Elliott

Tags: #Amazon.com, #European History

BOOK: Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830

13.61Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

35 Jan Verelst, Portrait of Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row. The Five Nations enter the world of international diplomacy as they manoeuvre between Britain and France. In 1710, when the English colonists were anxious to secure help from the mother country to conquer French Canada, they persuaded this Mohawk chief and three fellow Mohawks to go on an embassy to London to advance their cause. The four `Indian kings' made a great impression and were enthusiastically received at court. It was also hoped that the ambassadors would be sufficiently impressed by what they saw in England to persuade the rest of the Iroquois Confederacy to join the attack. In the event, many Iroquois volunteers joined the English expedition mounted against New France in 1711, but it ended in disaster at the mouth of the St Lawrence even before the attack was launched.

36 Bishop Roberts, Charles Town Harbour, watercolour (c. 1740). By the time the harbour of Charles Town (the future Charleston) was depicted in this watercolour by a resident artist, the city had become a flourishing Atlantic port. The rice grown on the plantations of South Carolina was shipped from here to Europe and the West Indies. The colony's rice exports paid for the imported luxury goods eagerly sought by the planter elite for the adornment of their mansions and persons.

37 Anon., The Old Plantation, watercolour (c. 1800). The survival of African culture in a New World environment. Plantation slaves, probably from a South Carolina plantation, appear to be celebrating a wedding with music and dancing.

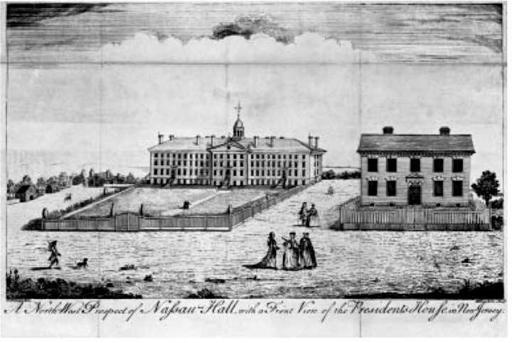

38 Henry Dawkins, A North-West Prospect of Nassau Hall with a Front View of the President's House. An engraving of 1764, which shows the College of New Jersey (the future Princeton University) eighteen years after its foundation in 1746.

39 Paul Revere, The Boston Massacre. This engraving, with its dramatic depiction of the moment on 5 March 1770 when a party of eight British soldiers turned their guns on a hostile crowd, circulated widely through the colonies and helped inflame the passions that would lead to revolt.

40 Anon., Union of the Descendants of the Imperial Incas with the Houses of Loyola and Borja (Cuzco, 1718). The painting commemorates a double union between the Inca and Spanish elites. On the left, St Ignatius Loyola's nephew, Don Martin Garcia de Loyola, governor of Chile, who was ambushed and killed in the Araucanian wars in 1598, and his wife, Dona Beatriz, the daughter of Sairi Tupac, who succeeded to the imperial rights of the Incas. Beside them is St. Ignatius holding the constitutions of the Jesuit Order. Above them to the left are shown the bride's parents, along with Tupac Amaru I, in the centre, who was executed by the Spaniards for rebellion in 1572. In the foreground on the right, the daughter born of this marriage, Dona Lorenza, is depicted with her husband, Don Juan de Borja. The bridegroom was the son of St Francis Borja, who stands behind him holding his emblem, a skull. The painting, depicting marriages that had occurred more than a century before, testifies to the pride of the eighteenthcentury nobility of Cuzco in their ancestral past.

41 William Russell Birch, High Street from the County Market Place, Philadelphia, engraving (1798). One of twenty-nine views of post-revolutionary Philadelphia, engraved by a British artist who arrived in America in 1794. The engravings were intended to serve as an advertisement 'by which an idea of the improvements of the country could be conveyed to Europe'. They give a lively impression of the handsome and prosperous city in which the First and Second Continental Congresses were convoked, and the Declaration of Independence signed.

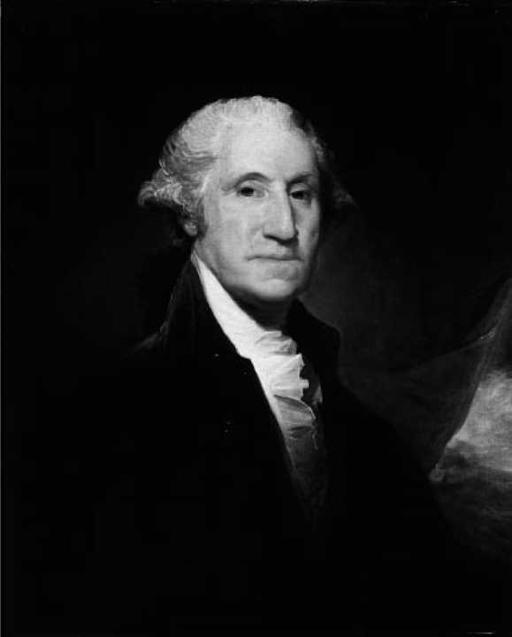

42 Patriots and Liberators 1. George Washington (1732-99) painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1796.

43 Patriots and Liberators 2. Simon Bolivar (1783-1830), miniature on ivory of 1828, after a painting by Roulin.

While British and Spanish American colonists in the later decades of the eighteenth century shared a growing disillusionment with their mother countries and with the Old World itself, the British proved to have a more impressive armoury of ideological weapons at their disposal for resisting the political assault that now confronted them. The population of the British colonies had long enjoyed access, through books, pamphlets and other forms of ephemeral publication imported from England, to a wide spectrum of political opinions. These ran from the high Tory opposition views of a Bolingbroke, through the orthodox doctrines of a Whig establishment comfortably settled on the constitutional foundations established by the Glorious Revolution, to the radical and libertarian doctrines of the seventeenth-century Commonwealthmen and their reformulation by eighteenthcentury publicists like John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon.1° These divergent approaches to the ordering of politics and society were readily available because the fault-lines created by the upheavals of the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution still ran through the British Atlantic community. Each time the tectonic plates shifted there would be a new eruption of political and religious debate.

There was little scope for such public debate in the more controlled environment of the Spanish Atlantic world. An unpopular royal minister, like Esquilache, might be overthrown by the action of the Madrid mob, but there was no opportunity in the Spain of the 1760s for a John Wilkes to emerge and mount a sustained challenge to authority through the spoken and written word. Lacking the ammunition provided by a metropolitan literature of opposition, creoles who were critical of royal policies therefore remained dependent on the theories of contractualism and the common good propounded in medieval Castilian juridical literature and the works of the sixteenth-century Spanish scholastics. During the first half of the eighteenth century the Jesuits updated this scholastic tradition by assimilating to it the natural law theories of Grotius and Pufendorf,ii but the political culture of the Hispanic world lacked the benefit of rejuvenating injections provided, as in Britain, by parliamentary and party conflict.

The opportunities for informed political discussion in the American viceroyalties were also narrowed by local constraints. Following the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767, a royal decree forbade the teaching of doctrines of popular sovereignty as expounded by Francisco Suarez and other sixteenth-century Jesuit the- ologians.12 The censorship of books was a further obstacle. It was normal practice in the Spanish Indies that no book could be printed without the granting of a licence by viceroys or presidents of the Audiencias. Such a licence would only be issued after its contents had been approved by the local tribunal of the Inquisition." Even if the process of inquisitorial vetting was often perfunctory, and the system of licensing by the civil authorities was open to corruption, bureaucratic controls inevitably impeded the circulation of ideas in a continent where vast distances and problems of transportation made inter-regional communication laborious and slow.

Other books

The Fantasy by Ella Frank

Killing Casanova by Traci McDonald

Last Ragged Breath by Julia Keller

The War of the Dragon Lady by John Wilcox

Captive-Sated (Dark Romance Series) by Suzanne Steele

Sharing Janice, Swinger's Fantasies, Episode 1 by Mia Moore

Earth Bound by Avril Sabine

Fruit of All Evil by Paige Shelton

Wild Justice by Kelley Armstrong