Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (16 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

There were the two linked promontories of Birgu and Senglea that made up the nucleus of Christian resistance, but these were interlinked with the fortress of Saint Elmo across the water on Mount Sciberras that provided the key to the best harbor. The main Ottoman camp at Marsa was six miles from the fleet anchored at Marsaxlokk, and the early skirmishes had revealed the need to guard the supply chain from ambush along its entire length. There were also the two forts in the hinterland to consider, that at Mdina and the other on Gozo, which provided potential centers of guerrilla warfare and rallying points if left unattended. One of these targets had to be chosen first; the others had to be managed. It would be necessary to split the army into sections. Perhaps twenty-two thousand fighting men was not so large a force after all.

Other things were concerning the commanders too. Piyale was edgy about the winds, less predictable in summer than those in the eastern half of the White Sea. The imperative to keep the fleet safe was his absolute priority. Shipwreck or a daring raid by enemy fire ships would commit the expedition to lingering but certain collective death at the hands of an enemy with reinforcements uncomfortably close at hand. Malta, lying under the eagle wing of Christian Sicily, was the king of Spain’s domain; sooner or later a counterattack was certain. The long lines of communication, the finite time frame, the inability to remain on Malta over the winter—all these things were weighed in the balance.

Relations between Mustapha and Piyale were tense as the options were discussed on May 22. The admiral and the general had issues about priorities and seniority; both were aware of Suleiman looking over their shoulders; he was there by proxy in his banners and flagship, more directly in the presence of his personal heralds—the

chaushes

—who reported back to him directly. Both Piyale and Mustapha were wellconnected within the Ottoman court; both were eager for glory and to avoid disgrace. The two were united only in their jealousy of Turgut, the third player in the sultan’s triangle of command, expected any day from Tripoli. Christian accounts provide vivid and probably highly imaginative accounts of the wrangles, the choices, the votes cast on the day—it is highly unlikely that any Christian slave was present in the pasha’s ornate tent—as they lobbied for their tactics.

In the end they chose the objective that Don Garcia had predicted they would: the little fort of Saint Elmo, “the key to all the other fortresses of Malta.” This decision had probably been taken months ago in Istanbul, well before departure, at a divan meeting on December 5, 1564, when engineers laid plans and models of Saint Elmo before the sultan, explaining that they had found it to be “on a very narrow site and easy to attack.” At the time Spanish spies in the city had filed a report back to Madrid that was eerily prophetic in all but one respect: “Their plan is to take the castle of St Elmo first so that they can get control of the harbour and put most of their ships there to overwinter and then capture the castle of St Angelo by siege.” Now Mustapha’s engineers studied the site again and were confident it would be an easy task, “four of five days” was the estimate; “losing St Elmo, the enemy would lose all hope of rescue.” But if they were confident of taking the fort quickly, there was also a note of defensiveness, even fear, in this decision. Saint Elmo would “secure the fleet, in which lay their safety, by drawing it inside the harbor of Marsamxett, out of all danger from prevailing winds and maritime disasters and all possibility of enemy attack…[and]…of all dying on the island without being able to escape.” Even at the outset they were pondering the implications of operating so far from home. For Piyale particularly, preserving the fleet was the key to everything. The commanders decided not to wait for Turgut to confirm this decision; time was pressing. They set to work straightaway.

Time was critical for La Valette too. When he learned of the Ottoman plan from escaped renegades, he was said to have given thanks to God; the attempt on Saint Elmo would buy a breathing space to repair the defenses of Senglea and Birgu and time to dispatch pleas to Don Garcia, Philip, and the pope for a rescue fleet. Work continued on the fortifications day and night; obstacles outside the walls that could provide sheltering positions for the enemy—trees, houses, and stables—were demolished; the whole population was engaged in hauling vast quantities of earth inside the settlements for running repairs to walls damaged by gunfire. All that the grand master had to do was persuade the garrison over on Saint Elmo to sell their lives as dearly as possible.

On May 23, the Ottomans started to transport heavy wheeled guns from the fleet to the Sciberras Peninsula. It was an immensely difficult journey over seven miles of rocky ground, involving large numbers of animals and men. The landscape echoed to the grinding of the iron wheels, the bellowing of the oxen, the shouts of exhausted men. Balbi watched the guns from Senglea: “We could see ten or twelve bullocks harnessed to each piece, with many men pulling the ropes.”

The defenders made their own preparations. As the Turks established their positions on the peninsula, the only safe way out of Saint Elmo was by boat from the rocky foreshore across the harbor to Birgu, a distance of five hundred yards. La Valette ordered the evacuation of some women and children who had taken refuge there, and he sent back supplies and a hundred fighting men under Colonel Mas, sixty released galley slaves, food, and ammunition. In all there were about seven hundred fifty men in Saint Elmo, the majority of whom were Spanish troops under their commander, Juan de la Cerda.

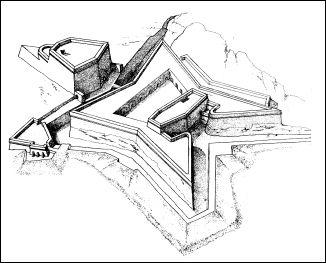

From the landward side, where the Turks were establishing their gun platforms, Saint Elmo presented a long low raked profile, like a stone submarine floating on the end of the rocky ridge. Two of the four points of its star faced the hill on which the Turks were establishing their position. The fort was protected at the front by a stone-cut ditch, and at the back on the seaward side by a detached keep, a cavalier, which reared up above the whole fort like the submarine’s conning tower. Hidden in the heart of the fort were a central parade ground—protected in front by a blockhouse—a cistern for water, and a small chapel to provide for the men’s spiritual needs. The hastily constructed triangular ravelin was outside the fort and linked to it by a bridge; it provided some protection from a flank attack, but to an experienced siege engineer looking down from the heights of Mount Sciberras, Saint Elmo looked small and vulnerable. There were numerous shortcomings; the fort’s design was poorly thought out and badly executed. It had low parapets and no embrasures to protect the men, so that no defender could shoot without making himself a clear target; its small size precluded the siting of many guns on the ramparts; it lacked sally ports from which troops could safely exit to clear the ditch of enemy infill or launch counterattacks. Worst of all, the angles of the stars were so sharp that there were large areas of dead ground beneath the ramparts upon which defenders were unable to fire. The Ottoman engineers’ assessment of the task ahead seemed reasonable. To all intents and purposes, Saint Elmo was a stone death trap.

Saint Elmo, showing the blockhouse and central parade ground, the cavalier at the rear, the ravelin on the left (Courtesy of Dr. Stephen Spiteri)

No army in the world could match the Ottomans for their grasp of siege craft, their practical engineering skills, their deployment of huge quantities of human labor for precise objectives, their ability to plan meticulously but to improvise ingeniously. Armies that had reduced castles in Persia and frontier forts on the plains of Hungary, who had dug trenches at Rhodes with such astonishing speed, who had, their enemies acknowledged, “no equal in the world at earthworks,” went about their task with dreadful skill. From the fort itself, and from across the water on Birgu and Senglea, the defenders watched with awe. The rocky terrain and the lack of topsoil and wood made trench cutting difficult, but the sappers pushed forward their spidery network of trenches “with marvelous diligence and speed.” Careful angles of approach shielded the work from the fort for a considerable time. Earth was transported from a mile away to construct gun platforms. Hundreds of men marched in long columns up the slopes of the hill with sacks of earth and planks of wood. The deep planning of this operation was astonishing; they had brought the materials and components for their gun batteries ready-made from Istanbul. The trenches advanced with sinister intent. Within a couple of days the Ottomans were entrenched at little more than six hundred paces from Saint Elmo’s ditch. Soon the Turks’ front lines had reached the edge of the ditch itself. They created two lines of raised earth platforms to mount their guns, and protected them with triangular wooden battlements filled with earth. Flags fluttered brightly from their forward positions; the guns were hauled painstakingly up the bare hill to their emplacements at the summit; other positions were established to bombard Birgu across the water. At night, transport barges rowed silently into the harbor of Marsamxett below Saint Elmo with bundles of brushwood for filling up the castle ditch. Across the water La Valette watched this activity with alarm and dispatched urgent messages to Don Garcia in Sicily.

By Monday, May 28, the Ottoman guns were starting to bombard Saint Elmo from the heights; by Thursday, Ascension Day in the Christian calendar, the Turks had twenty-four guns positioned in two tiers, wheeled guns that fired penetrating iron balls, and giant bombards, one a veteran of Rhodes, firing enormous stone ones. The initial bombardment was preceded by a rattling barrage of musket fire to prevent any defender from showing his head over the parapet, then the cannon opened up. The Ottomans started to pulverize the two star points facing outward toward the ditch and the weak flank toward the ravelin. From Birgu, La Valette did his best to disrupt this cannonade by mounting four cannon of his own on the end of Saint Angelo and pummeling the platforms that were visible on the ridge across the water. He was not without success; as early as May 27, Piyale was slightly wounded by a stone splinter; but the cost in gunpowder was too great to be sustained.

From the start the omens were not good for the defense. The men could hardly raise their heads over the parapet without being ready targets, clear against the summer sky. The janissary snipers with their long-barreled arquebuses waited in the trenches below for any sign of life. Their patience was extraordinary; they watched, concealed and motionless, for five, six hours at a time, sighting down the barrel, finger on the trigger, waiting like hunters for the prey. They shot thirty men dead in a single day. The defenders did their best to erect makeshift protecting parapets; at the same time they worked to reconstruct crumbling walls out of earth and whatever other materials came to hand. Within a few days, morale started to collapse: whenever the defenders risked a sighter at the Ottoman guns looming on the hill above, they were in danger of being picked off. The proximity of the trenches, the crash of cannonballs, and the patent shortcomings of the fort made it obvious that their position was not sustainable. As early as May 26 the defenders slipped a man across the harbor in the dark. Juan de la Cerda was one of Philip’s Spanish commanders and owed no allegiance to the knights. He gave La Valette and his council a blunt, uncomfortable, and public assessment of what the grand master already knew: the fort was weak, small, and without flanking defenses, “a consumptive body in continuous need of medicine to keep it alive.” It could hold out without reinforcements for eight days at the most. More resources must be committed.

This was not what the grand master wanted to hear. Everything in his calculations depended on Saint Elmo buying time for Birgu and Senglea to strengthen their defenses and for Don Garcia, thirty miles away in Sicily, to send a relief fleet. He ironically thanked the Spaniard for his advice and appealed to the defenders’ honor. At the same time he promised to send what was required: one hundred twenty men were ferried across under the command of Captain Medrano, who was now to be in charge of all the rebellious Spanish troops, as well as extra food and munitions. Wounded men made the journey back to the knights’ hospital at Birgu. The defenders’ morale was bolstered by these prompt actions but their underlying predicament remained unchanged. Smoldering dissatisfaction would soon break out again.

A regular interchange of small boats, apparently able to break the Ottoman naval blockade with impunity, carried messages to and fro between La Valette and Don Garcia in Sicily. The viceroy’s news was profoundly discouraging. There were innumerable delays in gathering ships and men. The logistics of assembling a task force were proving immensely complicated. Some galleys were still being fitted out in Barcelona; in Genoa, Gian’Andrea Doria had been waiting for soldiers from Lombardy; then it rained heavily and the sea was too rough to risk moving his ships. In Sicily, Don Garcia had five thousand men but only thirty galleys, and the Ottomans knew this. They could afford to disarm many of their own galleys and send the crews ashore to work, leaving seventy to patrol the coast. They pressed forward with the bombardment. La Valette confined this information to his small council.