Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (6 page)

Read Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World Online

Authors: Nicholas Ostler

Tags: #History, #Language, #Linguistics, #Nonfiction, #V5

As it turns out, the story falls into two major epochs, which divide at 1492. This is the beginning of the worldwide expansion of Europe and some of its languages. Before this point, languages almost always spread along land routes, and the results are regional: large languages are spoken across coherent, centred regions. After this point, the sea becomes the main thoroughfare of language advance, and spread can be global: a language can be spoken in distinct zones on many different continents, with its currency linked only by the sinews of trade and military governance that stretch across the oceans.

Besides this geographical difference, it is possible to see other gross patterns which distinguish the two epochs.

Before 1492, the key forces that spread languages are first literacy and civic culture, and later revealed religion. But when a community has these advantages its language is often spread at the point of a sword; without them, military victories or commercial development will achieve little. The general mode of spread is through infiltration: whole peoples do not move, but languages are transmitted by small communities and piecemeal colonies which do. But the foundation of English, which occurs in this period, appears to be an exception to all this.

After 1492, the forces of spread are at first much more elemental: disease devastates populations in the Americas and elsewhere, and the technological gap between conquerors and victims is everywhere much starker than it had been in the era of regional spread. But once the power balance moves back into equilibrium, with the stabilisation of the Europeans’ global military empires, it becomes hard to distinguish military, commercial and linguistic dominance. At first, travel is difficult, and language spread is slow, still based on infiltration. However, with the spread of literacy and cheaper transport, the mode switches to migration, as large European populations seek to take advantage of the new opportunities. In the twentieth century, this too eases off; but new forms of communication arise, continually becoming faster, cheaper and more comprehensive: the result is that the dominant mode of language spread switches from migration to diffusion. English is once again exceptional, as it has been uniquely poised to take first advantage of the new technologies, but its prospects remain less clear as the other languages, both large and small, settle in behind it. It faces the uncertain future of any instant celebrity, and perhaps too the same inevitable ultimate outcome of such a future. This is not least because, for the world’s leading lingua franca, the whole concept of a language community begins to break down.

But once informed with the varied stories of the world’s largest languages, our inquiry can move on to ask some pertinent questions.

How new and unprecedented are modern forces of language diffusion? Do they share significant properties with language spread in the past?

How will the age-old characteristics of language communities assert themselves? In particular, can all languages still act as outward symbols of communities? And can they effectively weave together the tissues of associations which come from a shared experience? Can each language still create its own world? Will they want to, when science—and some revealed religions—claim universal validity?

These are the questions we shall want to ask. But first we must examine the vast materials of human language history.

*

As such it is prominent in forming the present-day Top Twenty language communities, to be considered close to the conclusion of this book (see p. 527).

†

The widespread use of English in the European Union can be seen as Diffusion reinforced (after the UK’s accession in 1973) by Infiltration.

*

It is also an inherently dangerous term, hard to separate from sweeping attempts to evaluate the achievements of whole peoples. (See, e.g., Macaulay’s notorious verdict on Sanskrit- and Arabic-based cultures (see Chapter 12, ‘Changing perspective—English in India’, p. 496).)

*

This has led to the total omission of two important known language spreads, and one conjectured one. The Polynesian islands gained their dozens of closely related languages over the four millennia from 3000 BC in perhaps the most intrepid sustained exploration ever. And the Bantu languages spread across southern Africa over much the same period, beginning in Cameroon and ending at the Cape. Both of these stories are crucial to understanding the full pattern of languages in today’s world, but they are based purely on archaeology and linguistic comparisons. We have not a single word recorded from all the talk of those aeons. As for the geographical path of Indo-European, the ancestral language that is reconstructed to make sense of the evident systematic relationships among Hittite, Sanskrit, Russian, Armenian, Greek, Latin, Gaulish, Lithuanian and English, and many, many more, we can only speculate, and those speculations are the stuff of historical linguistics, not of language history.

LANGUAGES BY LAND

Two Italian opinions, separated by fifteen centuries, on the value of an imposed common language:

nec ignoro ingrati et segnis animi existimari posse merito si, obiter atque in transcursu ad hunc modum dicatur terra omnium terrarum alumna eadem et parens, numine deum electa quae caelum ipsum clarius faceret, sparsa congregaret imperia ritusque molliret et tot populorum discordes ferasque linguas sermonis commercio contraheret ad colloquia et humanitatem homini daret, breviterque una cunctarum gentium in toto orbe patria fieret.

I am aware that I may be quite rightly thought thankless and lazy if I touch so lightly on that land which is both the foster-child and parent of all lands, called by Providence to make the very sky brighter, to bring together its far-flung domains, to civilise their ways of life, to unite in conversation the wild, quarrelsome tongues of all their many peoples through common use of its language, to give culture to mankind, and in short to become the one fatherland of every nation in the world.

Pliny the Elder (AD 24-79),

Naturalis Historia

, iii.39The yoke of arms is shaken off more readily by subject peoples than the yoke of language.

attributed to Lorenzo Valla, Italian humanist (1406-57),

in his

Elegantiarum Libri VI

The Desert Blooms: Language Innovation in the Middle East

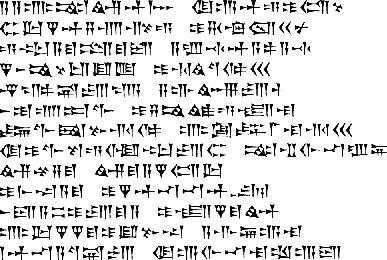

ayu ém ilī ém ilī | qereb šamě ilammad |

| milik ša anzanunzî | i akkim mannu akkim mannu |

| ēkšma ilmada | alakti ili apšti |

ša ina amšat iblu u u | imūt uddeš |

| surriš uštādir | zamar u tabar tabar |

ina ibit appi ibit appi | izammur elī la |

| in pīt purīdi | u sarrap lallariš sarrap lallariš |

| kī petě u katāmi |  ēnšina Šitni ēnšina Šitni |

immu ama ama | immš šalamtíš |

| išebbšma | išannana ilšin |

ina ābi itammš ābi itammš | elš šamā ’i |

| ūtaššašama idabbuba | arād irkalla |

| ana annāta ušta- | qerebšina la altanda |