Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (86 page)

Read Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World Online

Authors: Nicholas Ostler

Tags: #History, #Language, #Linguistics, #Nonfiction, #V5

The eastern Slavs who founded Russia were among the descendants of the Veneti who, as we have seen (see Chapter 7, ‘Einfall: Germanic and Slavic advances’, p. 304), populated the shores of the Baltic in the early first millennium AD; a large number of them had not travelled southward to populate the Balkans and invade Greece (see Chapter 6, ‘Intimations of decline’, p. 257), but had rather settled towards the east, in uneasy rivalry with Baltic tribes to their north-west, and the Uralian tribes, among them the Finns, to the northeast. Indeed, the claim is made that the majority of the original population of Rus were of Finnish descent and hence language. The Slavs would have settled among them in the first centuries of the second millennium.

These people spoke a language that was related to that of their German neighbours to the west, and that of their Baltic neighbours (Latvians, Lithuanians and Prussians) to the north, but noticeably softer in its tone, in that consonants were palatalised and often affricated before e and i:

*

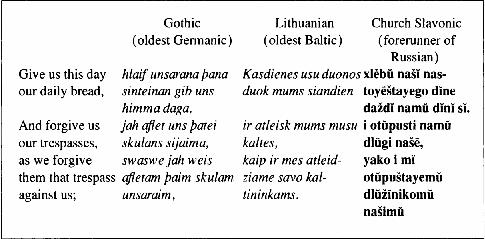

as a result, the sounds š, c and ž are highly prevalent; compare the middle of the Lord’s Prayer in the oldest forms of their languages:[

note

*

on next page

]

The eastern Slavs, whose language would go on to form modern Russian, Ukrainian and Belorussian, almost close enough in form to be considered dialects, had been farmers rather than nomads, although the quest for furs was always a priority on their eastern frontier. By the end of the first millennium they were established in a vast forested area which ran from the Baltic coast near Novgorod due south to Kiev, and out to the east as far as Kazan. Although the people spoke Russian, their aristocracy was made up of Vikings (known as

varyági

or Varangians), seafarers who had invaded along the waterways from the Baltic, and who at first would have been Norse-speaking, but like so many Germanic conquerors had given up their own language. They organised the Russians on the basis of capitals ever farther south, in Novgorod, Smolensk and, in 882, in Kiev. The Dvina and Volkhov were linked by portages with the Dnieper, and so communications were established with the Black Sea, and thence the Byzantine empire. In 988 this link resulted in the conversion of Vladímir (’conquer the world’) and his Kievan court to Orthodox Christianity. In the following four centuries, the religion spread to cover the full range of eastern Slavs.

To the south of the Kievan domain was grassy steppe, dominated in the second half of the first millennium by a series of largely Turkic-speaking nomadic peoples on horseback, who kept arriving from the east, conquering and settling down as the new masters: Avars, Khazars, Bulgars, Magyars, Pechenegs, Kipchak-Polovtsians, Alans, and finally Genghis Khan’s Mongols. There was persistent warfare over the period, immortalised in the first surviving work of Russian literature,

Slovo o Polku Igoreve

, the Lay of Igor’s Campaign, set in 1054 and apparently written in the twelfth century:

Uže, knyaže, tuga umi polonila;

se bo dva sokola slėtėsta su otnya stola zlata

poiskati grada Timutorokanya

,

a lyubo ispiti šelomomi Donu.

Uže sokoloma krilitsa pripėšali poganïxu sablyami

,

a samayu oputaša vu putinï želėznï…O Prince, grief has now taken your mind captive;

for two falcons have flown from their father’s golden throne

to gain the city of Tmutorokan,

*

or else to drink of the Don from their helmets.

The falcons’ wings have now been clipped by the sabres of infidels,

and they themselves are fettered in fetters of iron…

At last the Mongols, constituted as the khanate of the Golden Horde, sacked Kiev and ended that city’s hegemony of the Russians in 1240. Mongol suzerainty, entailing a heavy burden in tribute, came to be recognised all over the Russian territories, even in 1242 by Prince Alexander

N

y

evskiy

up north in Novgorod, despite his recent victories over the Swedes and the Teutonic knights. It has been reckoned that this early subjection, which lasted for almost three centuries, and was definitively ended only by the victories of Ivan IV

Groznïy

(’the Terrible’), planted a lasting pessimism in the Russian soul, establishing a deep-seated tradition of serfdom at the bottom of society, and absolutism at the top.

The new Russian polity, when it came, would be based not on Kiev but on Moscow, 800 kilometres (by Russian measure, 750

vërst

) to the north-east. In 1328 the Orthodox Metropolitan moved his seat accordingly. Moscow had a good central position within Rus, and its triumph over the other city-states was partly due to the fact that it stayed unified, having the luck to produce a single male heir in each generation in the fourteenth century. The Grand Prince of Moscow, Dmitriy Donskoy, defeated the Mongols in 1380, and in 1480 Ivan III finally repudiated their suzerainty. The Moscow princes (

knyazi

) were going up in the world: about the same time, Ivan married Sophía Palaiológou, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor (deposed in 1453), and claimed to have inherited imperial status through a special donation of insignia from Constantinos Monómakhos (Byzantine emperor) to Vladimir Monomakh (Prince of Kiev) in the eleventh century. Moscow began to be represented as the Third Rome, and the monk Filofey of Pskov wrote to Ivan III at the end of the fifteenth century: ‘Thou art the sole Emperor of all the Christians in the whole universe…For two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and there shall be no fourth.’

44

In 1547, Ivan IV was the first ruler to be crowned not prince but

T

s

ar

y

, that is to say (in Russian pronunciation) Caesar.

*

He went on to prove he deserved it by conquering and incorporating both the major remnants of the Golden Horde, the Turkic khanates of Kazan (in 1552) and Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea (in 1556). The local nobility were absorbed into the Russian, and so a process of assimilation was begun. With these steps, Russians began their career of imposing themselves on other language communities, an imperial expansion of their language zone which would continue for the next three and a half centuries, and end up in the twentieth century with nominal coverage of the whole northern half of the land-mass of Asia.

The greater part of this spread came about without the active initiative of the Tsar, his government or his armies. The immediate effect of the conquests of Kazan and Astrakhan was to remove the barrier to Russian penetration out towards the east; and this opportunity was soon taken up. The Stroganov family happened to hold the monopoly of fur-trading and salt-mining: they now engaged an army of Cossacks from the Don area, initially to protect against the khan of western Siberia, but then to attack the khan’s capital on the lower Irtysh. The capital fell in 1582. Over the next fifty-seven years the Cossacks advanced rapidly and consistently, and in 1639 they reached the Pacific, founding the city of Okhotsk in 1648. They proceeded to move south down the coast to the Amur river, but were soon compelled by the Chinese to give up the area bordering Manchuria; the Sino-Russian border was defined, effectively for two centuries to come, at the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689.

Although their name is Turkic,

†

the Cossacks spoke Russian. They were a large but miscellaneous group of horsemen, militant Christians, disorderly but proud, who had taken up nomadic ways in the long centuries of threat and domination by Turkic nomads, and were found all over the southern steppe country from Poland and Ukraine through to Kazakhstan. During their advance across Siberia, they built fortresses at the major river crossings, some of them now major cities (among them Tomsk in 1604, Krasnoyarsk in 1628, Yakutsk in 1632); but they only scantily settled the lands through which they advanced. They were followed by a dusting of soldiers, missionaries, tax-collectors (exacting the tribute, called by the Turkic name

yasak

, that was paid in fur pelts) and a very few Russian settlers, either peasants looking for land, or political exiles sent by the government; but the linguistic impact was at first thin. The Russians remained congregated along the major rivers, surrounded at first by a diversity of ancient Siberian peoples. Over the next three centuries, as extractive industries began to develop, they were joined by more settlers from the west.

This early expansion to occupy Siberia, taken together with the Russian heartland in the north European plain, accounts for most of the area that is now part of Russia. The non-Russian populations there were always too sparse, and too remote from any non-Russian source of civilisation, to organise independent states.

This was emphatically not true of Russia’s other neighbours, most of whom found themselves succumbing to Russian conquest in the four centuries of Russia’s expansion. They fall into four groups: the Slavic-language states to the west; the Baltic and Uralic-language states to the north-west; the Caucasian states to the south; and the central Asian states to the south-east. As it happens, at the time of writing in the early twenty-first century, most of them have regained their independence, and are seeking to rebuild links with their pre-Russian pasts; the few that have not, notably the Chechens and Ingush of the Caucasus, are seeking more or less bloodily to secede. It is a notable fact about Russia’s old colonies that very few of them value highly the historic links symbolised by use of the Russian language, or indeed the potential for collaboration that Russian would give them if accepted as a lingua franca. It is worth enquiring why, alone of the European imperial languages, Russian has left this rather poisoned inheritance.

The Slavic-language states of the west include not just Ukraine (

Ukraína

, ‘On the Border’) and Belarus (

Byelarús

y

, ‘White Rus’), but also Poland (

Pól

y

ša

, ‘Open Plains’).

*

Early Russian expansion in this direction did not at first expand the area of Russian speakers, since the kingdom of Lithuania had taken advantage of the destruction of Kiev in 1240 to take over most of the western Russian lands. Later, in 1385, Lithuania entered into a close alliance with Poland through a dynastic marriage, and the two countries were formally confederated in 1569, so in attempting to regain the western Russians, the new power centre in Moscow was actually facing a struggle with Poland. When Ivan the Terrible took up arms in the sixteenth century, he was significantly less successful in expanding against this Christian kingdom to his west than he had been against the Tatars to his east. Twenty-five years of Livonian wars from 1558 served only to lose Russia its foothold on the Baltic, and to destabilise its monarchy. In the

smútnoye vrémya

, the ‘confused time’, that followed, Poland invaded and briefly held Moscow from 1610 to 1612. Nevertheless, when order was restored in Russia under the new Romanov dynasty in 1613, the westward pressure was reasserted, and gradually Moscow’s sway was increased: Smolensk, Kiev and the eastern Ukraine were gained by Tsar Aleksey in 1667; and the rest of the Ukraine and Belarus by Tsaritsa Yekaterina II (Catherine the Great) in 1772 and 1793.

At this point, most of the Russian speakers were back under a Russian government, arguably for the first time since 1240, but a rebellion by Poland against the settlement of 1793 led to war, which Russia won decisively; the result was that almost immediately, in 1795, Russia gained control of the whole east of Poland up to the Neman and Dniester rivers, a situation that prevailed until the remapping of Europe that followed the First World War in 1918. Linguistically, this control had little effect: although the Polish language is fairly closely related to Russian, it is less so than Ukrainian and Belorussian; above all, the Poles’ political and religious history (as a Catholic nation) had been quite distinct, and in fact their literacy and general standard of living far exceeded those of the Russians. To start with, under Tsar Aleksandr I the country was accorded a separate constitution—but the Tsar found it hard to respect its terms; later, especially after 1863-4 (when Poland rebelled), attempts were made at ‘Russification’. Among other measures, Russian was imposed as the language for official business; and not only the University of Warsaw but all Polish schools were required to operate exclusively in Russian. This proved unworkable, and Polish survived.

By contrast, about the same time, in 1863, a Ukrainian language law was introduced, far harsher, banning publication of all books in Ukrainian besides folklore, poetry and fiction, and was followed up in 1867 by a further ban on imports of such books from abroad; Ukrainian was prohibited on the stage too. This was more effective. Ukrainians were encouraged to see themselves as ‘Little Russians’—conveniently for the Russians, since only if Ukrainians could be classed with them would Russians make up a majority of the population in the empire.

*

The Minister of the Interior wrote in 1863: ‘there never has been a distinct Little Russian language, and there never will be. The dialect used by the common people is Russian contaminated by Polish influence.’

45

And in 1867 the rector of Moscow University could make the appeal: ‘May one literary language alone cover all the lands from the Adriatic Sea and Prague to Arkhangelsk and the Pacific Ocean, and may every Slav nation irrespective of its religion adopt this language as a means of communication with the others.’

46