England's Mistress: The Infamous Life of Emma Hamilton (25 page)

Read England's Mistress: The Infamous Life of Emma Hamilton Online

Authors: Kate Williams

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Leaders & Notable People, #Military, #Political, #History, #England, #Ireland, #Military & Wars, #Professionals & Academics, #Military & Spies

O

n a warm night in July 1787, Sir William Hamilton assembled his most distinguished guests in his fine rooms looking out to the bay. After a lengthy dinner, he plied them with the finest wines from his cellars and made them a surprising promise. If they joined him upstairs in the reception rooms, there would be unlimited port—and something he vowed they had never seen before. When they were all assembled, he called them to hush and servants snuffed a few of the candles. In the gloom, they could just catch sight of a female figure draped in white, her dark hair flowing around her shoulders. As she came closer, they recognized Mrs. Hart, Sir William's pretty, witty mistress, who had been laughing at their jokes, flushed with gaiety, entertaining them with anecdotes about England. But now she was pale and almost ethereally composed. Taking up the shawls that lay at her feet, she began to swathe them around her, to kneel, sit, crouch, and dance. They quickly realized that she was imitating the postures of figures from classical myth. First she pulled the shawls over her like a veil and became Niobe, weeping for the loss of her children; then, using them to make a cape, she was Medea, poised with a dagger, about to stab. Then she pulled the shawls around her into seductive drapes, becoming Cleopatra, reclining for her Mark Antony.

Almost as soon as they had begun to predict her next pose, she disappeared. They sat openmouthed, as the servants relit the candles and offered more wine. Some of them shook themselves out of their dazzled state to nudge Sir William. Where had she learned it? they pressed him. Could she do it again? Behind the scenes, readying herself to come out and bask in their praise, Emma smiled as she heard her lover say that if

they wanted to see her again, they would have to come on another evening—if he could find the space. There was already something of a waiting list to see Mrs. Hart's Attitudes.

Emma began developing her Attitudes soon after she settled at the palazzo. Early on, she asked Greville to send out for more shawls, as "I stand in attitudes with them on me." Romney's sketches had given her an awareness of Greek and Roman dress, and she had struck classical poses for Greville when she was not playing the repentant Magdalen. He boasted to his uncle that "Lacertian or Sapphic, or Escarole or Regulus; anything grand, masculine or feminine, she could take up." Sir William's collection of statues, the paintings of nymphs on the wall of the Villa dei Papyri at Pompeii, and the antiquities for sale in Naples gave her the opportunity to study classical forms at first hand. She would also have noticed the modern Italian tradition of pantomime, often performed on street corners, in which the performer acted out moods with the use of masks. At the same time she took regular lessons in dance, learning ballet steps, including sweeping turns and bends. She naturally progressed to borrowing postures from the pictures and statues of nymphs and goddesses she had seen.

She combined her dance training and her modeling at the Temple of Health and for Romney with influences she collected in Naples to create her Attitudes, an extraordinary fusion of eighteenth-century dance with classical costumes and references, and a truly innovative art form.

Ballet dancers often practiced in plain shifts and shawls, and Emma would have worn a similarly loose dress that tied around the waist with shawls draped around her shoulders. When designing her outfit for the performances, she remembered the pattern of her tunic at the Temple of Health and the draped costumes she wore while modeling for Romney, as well as the local peasant costume, a Grecian-style dress, worn particularly on the islands in the Bay of Naples. Emma employed her dressmaker to produce dance dresses that were fuller at the waist and arms, giving a more gathered effect.

For her first performances to friends, Emma held poses in a black box rimmed with gold. She soon made use of the whole room. By the spring of 1787, she felt ready to show Goethe, who was traveling through Europe to enjoy some of the celebrity of his smash hit

Sorrows of Young Werther

and to relax after a punishing schedule of work. The great man watched the

Attitudes two nights in a row and was quite delighted, praising the Greek costume, her "beautiful face and perfect figure," and dubbing them.

She lets down her hair, and, with a few shawls, gives so much variety to her poses, gestures, expressions, etc, that the spectator can hardly believe his eyes. He [the viewer] sees what thousands of artists would have liked to express realized before him… standing, kneeling, sitting, reclining, serious, sad, playful, ecstatic, contrite, alluring, threatening, anxious, one pose follows another without a break. She knows how to arrange the folds of her veil to match each mood, and has a hundred ways of turning it into a head-dress.

1

Once the gossips found out that Goethe loved the Attitudes, hundreds, perhaps thousands, of tourists followed in his wake. Nearly twenty-five years later he included a scene in his novel

Elective Affinities

in which beautiful young Luciane thrills her audience with Attitudes. Emma's performance for Goethe when she was twenty-two ensured that she would be asked to present Attitudes for the next thirty years—a move she only occasionally regretted.

Another early spectator was Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, who marveled at Emma's ability to "suddenly change her expression from grief to joy… With shining eyes and flowing hair she appeared perfect as a bacchante; she could then change her expression immediately and appear as sorrowful as the repentant Magdalene…. I could have copied her different poses and expressions and filled a gallery with paintings."

Soon, every guest at the palazzo demanded to see the Attitudes. One raffish French visitor, the Baron de Salis, described how Emma, "covered herself with flowers, gives a living spectacle of masterpieces of the most celebrated artists of antiquity. She is very obliging and gave a performance to a little group of us. You have to have seen her to conceive to what degree this lovely figure enabled us to enjoy the charms of illusion." Adelaide d'Osmond, later the Comtesse de Boigne, a young refugee from Paris, described how Emma clad herself in a white tunic, her hair over her shoulders, and took up two or three cashmere shawls, an urn, a lyre, and a tambourine.

With this scanty equipment and in her classic costume, she would take up her position in the middle of the drawing room. She would throw over her head a shawl which trailed to the ground and which covered her entirely, and thus hidden she draped herself with others. Then she would lift the shawl suddenly or sometimes throw it aside altogether; at other times she would half slip it off, and it then served as a drapery for the model she personified.

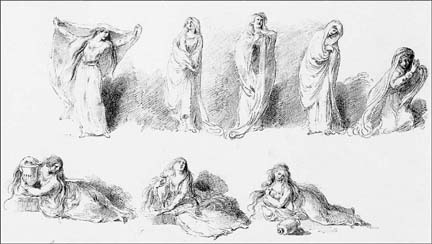

Attitudes of Lady Hamilton, by Pietro Antonio Novelli (1791). Novelli's drawing shows Emma using her shawls to move through the poses, ending with a drunken bacchante, revealing the clever manipulation that thrilled Goethe and made her one of the biggest tourist attractions in Europe.

To the young girl's excitement, Emma sometimes used her in her performances.

One day she made me kneel before an urn with my hands joined in an attitude of prayer. Leaning over me, she seemed to be absorbed in grief and we were both dishevelled. Suddenly she stood upright and, withdrawing a little, she seized me by the hair with such a sudden movement that I turned round in surprise and even a little fear, for she was brandishing a dagger! Enthusiastic applause from the artist spectators was heard, accompanied by the exclamations of “Bravo le Medea!” Then, drawing me towards her bosom with the semblance of protecting me from the wrath of heaven, she wrung from the same voices the cries of “Viva la Niobe!”

2

The comtesse's report shows how the Attitudes worked as a type of parlor game or charades, in which the audience competed to guess the posture

she assumed. As Emma knew, there were hundreds of visitors in Naples eager to show off their classical knowledge.

Emma soon became one of the biggest tourist attractions in Naples, and the political and cultural elite of Europe flocked to see her. Modern researchers claim that Sir William created the Attitudes, but there is no evidence for this. No spectators, even those who found her dismayingly vulgar, credit the idea to her lover, for they knew he was ignorant about fashion and dance. As they recognized, Emma borrowed poses she had struck in Romney's studio, recalling the artist's quest to unite classical models with modern sex appeal. Some implied that she learned to pose in the brothel, and indeed the word

attitude

was often used to refer to postures by courtesans. As one put it, she "improved her skill in Attitudes by the study of antique figures, from which she learned a variety of the most voluptuous and indecent poses."

3

Like the gossip columns in the newspapers already dropping teasing hints about Emma's performances, the guests describe Sir William as an enthusiastic admirer, awed by his lovely mistress's skill. If he took a role, it was to encourage her to dance around his finest vases in the hope that one of his visitors might want to buy them.

The Attitudes reflected Emma's endeavors to educate herself about classical culture by reading in her lover's library and accompanying him on his trips to Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Portici, as well as to excavations of tombs in search of new vases. In an illustration at the front of one of his catalogues, Emma is pictured in her signature white muslin, peering into a tomb. After listening to Sir William and his friends, she soon had the same smattering of knowledge about classical myths and history as any traveling squire, and her performances were created to suit just such an individual. The Attitudes were neither esoteric nor even accurate, but a hit parade of popular classical stories: Clytemnestra and Niobe, the more attractive goddesses; Iphigenia preparing to sacrifice herself; Helen of Troy; women seduced by Zeus; Cleopatra waiting for Antony; as well as a Magdalen. Since all travelers hoped to see Titian's

Danae

at Caserta, the corresponding attitude was always a reliable crowd pleaser as Emma posed as the title figure, a princess visited by Zeus disguised as a shower of gold.

Travelers wandered around Pompeii and Herculaneum hoping to be, as William Beckford put it, "transported bodily into the realms of antiquity," but feeling guiltily bored by the mass of soil and dirt. Much remained overgrown because the king refused permits to excavate, dreading anyone finding anything better than his own collection of antiquities. Although guides hunted out the sites of brothels and cafés to please the tourists, few

were able to imagine Pompeii as a Roman city.

4

Without films or plays to depict classical times (the Neapolitans hardly ever performed classical plays, for they preferred comic farce), they craved a performance that might give them an idea of classical Italy—and also encapsulate the essence of the modern country and its people. Emma fulfilled their desire. As the Comtesse de Boigne suggested, she showed them "the poetic imagination of the Italians by a kind of living improvisation" in easily digestible form. Beloved particularly by tourists who felt ashamed about preferring the shops to grimy ruins they could not understand, Emma's performances were seen as reviving the ancient past. The Attitudes soon became crucial to any self-respecting visitor's grand tour and essential to his descriptions of his encounters with classical culture.

Actors in England and Europe were pigeonholed into either comic (usually sexy) roles or parts as a tragic hero or heroine and were seldom allowed to perform both. Emma's audiences were stunned by her ability to move swiftly from tragic to comic postures. One onlooker recalled that he had

never seen anything more fluid and graceful… at one moment I was admiring her in the constancy of Sophonisba in taking the cup of poison… afterwards, changing at a stroke, she fled, like the Virgilian Galates… or else she cast herself down like a drunken bacchante, extending an arm to a lewd satyr.

5

Male spectators wished that Emma would strike erotic poses. A Parisian aristocrat, the Comte d'Espinchal, declared that she should forget dreary Minerva and dance about as lovely Hebe, Venus, and the Graces, then recline in a sumptuous boudoir and pretend to be "Cleopatra ardently greeting Mark Antony."

6

Since Emma performed from her early twenties until her late forties, the Attitudes were constantly changing. Her performances never fell out of favor because she kept up with the latest fashions, styles, and issues, incorporated new references, and altered her props and costumes. As she became more experienced, she gave roles to guests and servants, retained hairdressers to vary her look, and added songs. She tried hard to use her face to show the change of mood. Her audience were habituated to seeing acting at a distance onstage, in which loud noise and exaggerated movement often took the place of communication, and they found her ability to show different emotions through facial expression truly startling.