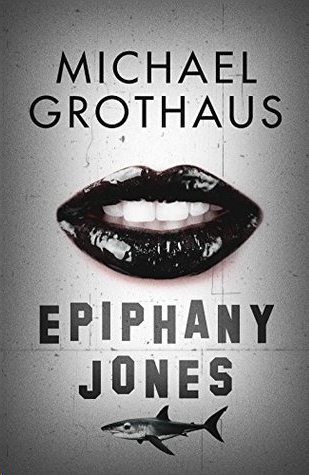

Epiphany Jones

Authors: Michael Grothaus

Tags: #Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Crime, #Humorous, #Black Humor, #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Mystery & Detective, #General

Michael Grothaus

For m.e.

And for the figments that live in our heads at three in the morning.

- Title Page

- Dedication

- 1:

The Dream - 2:

Van Gogh - 3:

Figments - 4:

Assassins - 5:

Occam’s Razor - 6:

Joan of Arc - 7:

Spork - 8:

Elmer Fudd - 9:

The Videotape - 10:

Sharks - 11:

Horny Halfling - 12:

Stockholm Syndrome - 13:

Public Relations - 14:

Road Trip - 15:

Mexico - 16:

The Clone - 17:

Names - 18:

The Education of Epiphany Jones - 19:

Teeth - 20:

Headlights - 21:

Perro - 22:

Judas - 23:

This Is Your Life - 24:

God - 25:

Lost in Translation - 26:

The Autobiography of Epiphany Jones - 27:

Reason - 28:

The Murder - 29:

Rape - 30:

Portugal - 31:

Caged Parakeet - 32:

Bela - 33:

Scrabble - 34:

The Mountain - 35:

Virginity - 36:

Jack-o-Lanterns - 37:

Vikings and Fairies - 38:

Tampons - 39:

Carnation Revolution - 40:

Cannes - 41:

Bullets - 42:

Gypsies - 43:

Memory - 44:

Rewind - 45:

The Secret History of Epiphany Jones and I - 46:

Time to Party - 47:

Coming Attractions - 48:

Passages - 49:

Lemon Meringue - 50:

Freefall - 51:

Hanna - Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Copyright

T

onight I’m having sex with Audrey Hepburn. Audrey’s breasts are different from the last time we fucked; they’re bigger, not as firm. There’s a hint of a stretch mark on the left one. The leading lady is bent over, gripping the bedpost. Her pink panties are slid down and pinched in place by the fold where her legs meet her ass, so my rod has the most access with the least possible effort. She’s looking back at me, eyes sparkling and fixed, with a slim PR smile. I’m going like a jackhammer, sweating, shoulders cramping, but her face is as placid as a sleeping bunny.

And I’ve got to slow down; it’s only been three minutes. But who am I kidding? So I let it all out as I gaze at Audrey’s face. And for eight seconds I’m calm, relaxed.

There’s a loud crack under my foot. It’s Emma’s picture. My little sister. My sweet, dead little sister. My thrusting must have knocked it off the desk. I always turn her around when I do this. No matter how old the photograph is you don’t want the image of someone you used to know watching you while you squeeze one off. The cracked glass has scratched Emma’s face. She’s now got a little white-cotton scar over her right cheek.

For the next three minutes I straighten the items on the desk.

Seven minutes after that I’m hiding all traces of fake celebrity porn from my desktop. Just in case my mom comes over.

Then. when I notice it’s four in the morning, I get that guilt.

Why did I do this? I have to get up in three hours, for God’s sake!

I tell myself I won’t do it again. I promise. I pinky swear, you know?

And look, maybe you pretend you’d Never Do Such Things; that you’d never stoop so low as to jerk off to actresses whose heads have been pasted onto a porn star’s body. But this is better than seeing prostitutes or shooting heroin. It calms me down. It’s harmless. Besides, it’s temporary. It’s just what guys do when they’re on a break from their significant others. And anyway, the best part of these late-night jerk-off sessions isn’t even what came before, it’s what comes next: the clarity that comes after the guilt fades; the realisation of everything that’s wrong in your life and the vow you make to change it.

I need to lose weight. I need to be more outgoing. I need to save money. I need to get a better job. I need to, I need to, I need to.

This clarity is like the previews for next week’s episode – the promise of new, exciting adventures to come. It’s the trailer of what you can do to improve your sorry life.

But tonight the clarity doesn’t happen. Just like the last few weeks. No big ideas. No Nirvana. My life feels like a rerun.

I know how tonight will end. I won’t fall asleep for too long. When I do it will come again: that same dream I’ve had for the last three nights.

And yes, it is odd to have exactly the same dream night after night.

And no, I don’t know what the meaning is.

When it begins it’s black and I can’t see anything, but I can feel my mind floating through the nothingness. Then, slowly, a figure fades in. It’s a young girl. Fourteen, maybe fifteen. Her frame is petite and doesn’t fully fill the light-blue dress she is wearing. Her face is small and round. Her hair, pulled back tight around her head, is black like a raven’s folded wing. Her skin, white as cream. And curiously, her left ear is mutilated. It looks like a piece of her lobe was torn right off.

And for some reason, I know she is The Deliverer.

But I don’t know what that is.

We’re in a silverware factory, of all places. The factory is abandoned. Teaspoon after teaspoon rusts in boxes on roller conveyors. Forks dangle from strings overhead. Three furnaces fill the far corner of the room. Their mouths gape, revealing long-extinguished insides. Behind

them, scorch marks on the brick walls. The floor planks are stained dark.

There’s a hint of a cleft in the girl’s chin and a slight tremble to her lip. The soles of her pale feet are black with dirt and dust and soot. She looks around frantically.

And I feel for this girl. She’s terrified.

She’s terrified because there are people coming. Bad people. I hear them outside, the people coming for her. Their silhouettes cast quick blue shadows as they dart past the windows, cracked and yellowed from chemicals and soot.

It’s early evening. Outside, crickets scream in the tall grass. The strangers thunder at the tin sidings. They rip and howl and shout in bizarre tongues as they claw at boards nailed over a doorway.

And inside, this little girl, she just stands in place now.

And a voice is heard: ‘An awakening is needed in the west.’

And the girl, she begins to cry.

Then they’re in, the strangers. Faceless forms charge her. I know they’ll kill her. I look away, there’s nothing else I can do. But when I look back, the girl has grown. Now she is maybe twenty-something. And I would think her beautiful if she weren’t so terrifying. Her smile is crooked and cold. Her eyes beget madness. She has a sickle in her hand. It’s funny too, because it looks just like the Nike logo. And swinging this Nike Swoosh, she kills the first three men.

Swoosh!

There goes one head.

Swoosh!

Another.

Just Do It.

And as she’s shortening people one by one, I start to focus on the dark hollow of the central furnace. I see something that leaves me feeling helpless and empty. I see myself hiding in the darkness of the furnace’s belly. I’m curled up, naked and crying. I’m seventeen years old.

And I’m praying not to be seen.

I

wake feeling like I haven’t slept.

The TV mutely plays an episode of

Mr Ed

. Wilbur and the talking horse are in astronaut suits. It’s the one where Mr Ed tries to convince Wilbur that they can build a ship to the moon. And why not? If your horse can talk, it sure as hell can build a space shuttle.

I reach for a balled-up dirty sock on the floor and spy a lone yellow pill sunk into the carpet next to it. So I do have one left. I really should take it.

I really should do my laundry, too. Tomorrow. Both tomorrow.

I stumble into the kitchen and grab the box of cereal with a white cartoon rabbit on the front. The microwave clock shows just how little time I have. I spoon my breakfast into my mouth, but by the time I get to the museum I’m still twenty minutes late. The moment I step into the Grey Room my boss starts complaining.

‘I need that Chagall done by eleven.’

‘Sorry, Sir. I was jerking off till five in the morning,’ would be the honest thing to say. But this guy, he probably hasn’t got it up in twenty years. He wouldn’t understand.

‘Sorry, missed the bus.’

‘Today is the last time you miss the bus. Understand? By eleven,’ he orders and walks back into his office.

I turn on the Mac. It’s got a grey desktop that perfectly matches the grey walls and grey everything else in this room. No wonder I’m depressed.

I’m a Colour Imaging ‘Specialist’ for the Art Institute of Chicago.

It’s my job to make sure all the paintings you see in those art appreciation textbooks nobody could give a damn less about have accurate colour representation – so the periwinkle blues actually look periwinkle blue and the Venetian reds, Venetian red.

And let’s get something straight about my title. There’s nothing ‘special’ about me. Nowadays companies will throw ‘specialist’ or ‘consultant’ into any job description. It’s their way of tricking you into thinking you’re important.

But a ‘specialist’ is one step above a peon and a thousand levels below anyone who matters.

Same thing goes for all you ‘consultants’. Let’s be real, you don’t advise your company about anything. You’re a salesman. You’re Willy Loman and you’ve already got one foot in the grave.

‘Hey, buddy,’ Roland calls out before he’s even in the room. ‘Here’re more negatives for that Chagall. Donald wants them by eleven, I think.’

No joke.

‘Thanks,’ I say, powering on the scanner. Roland looks like a failed male porn star: a little too old, a little too thin, a little too boney. Most disturbing though is that he shaves his arms every day. He does this so everyone can clearly see his stupid sleeve tattoo, which runs from his wrist to his elbow. And I swear to God, I’ve never seen him without his shirt sleeves rolled up.

‘Hey, you want to see it?’ Roland asks with the excitement of a twelve-year-old who’s just found his father’s nudies.

‘They’ve brought it to you?’

Roland grins.

‘I can’t. I’ve got to get this done.’

Roland shakes his head. ‘Check it out with me. It’ll take five minutes.’

My sleep-deprived mind doesn’t have the power to argue, so I follow him down the hall to his photo studio. What would normally be a thirty-second walk takes minutes because of all the plastic sheeting and disassembled scaffolding in the hall. This whole wing is a mess because of the renovation of the museum. The whole time I’m glancing over my shoulder to see if Donald is going to storm out and bust me. The whole

time Roland keeps jabbering about ‘It’, his voice wriggling through the sludge in my head like a tapeworm.

And when we finally get to his studio there It is, on an easel, just like it probably was a hundred and ten years ago. It’s small: eleven inches by eight inches.

‘Careful!’ Roland shouts. He’s caught a tripod I bumped into. ‘That’s ten million dollars right there.’

That’s all I need. Donald would end me if I damaged a painting. The tripod, it’s this old thing from the seventies. The MiniDV camera makes it top heavy. Its plastic legs are fractured in places. Anything heavier than the camcorder would snap it.

The way Roland is looking at me, he’s wondering how I get through each day.

‘Why don’t you get the museum to get you a decent one?’ I say.

‘I’ve tried,’ Roland answers like I shouldn’t have even needed to ask. ‘The renovation is cutting budgets from every department.’

The thing with Roland, he’s friends with my mom, and that’s where he gets it. Everything he says to me has a ‘

you should know this

’ inflection to it.

Roland’s desk is cluttered with fading flash screens, digital-camera card-readers, a week-old

Sun-Times

and books on outdated versions of Photoshop. But at least he’s got a fairly new Mac. The one they make me work on barely gets by. Sticking out from under a pile of old prints is a

Hollywood Reporter

with a picture of Penelope Cruz on the cover. And out of the corner of my eye Roland is giving me a pompous smirk. He pretends to himself that he knows what I’m thinking.

Above his mess of a desk is a framed article that’s clipped from the

Chicago Tribune

. In the article there’s a photo. In it Roland stands next to Donald and the director of the museum. All three wear stupid Masters of the Universe grins. In the right-hand corner there’s a picture-in-picture of the Van Gogh right next to Roland’s ridiculous face. And, OK, maybe I am a little bitter. He helped the museum obtain the Van Gogh. It’s on loan from the private collection of his old boss. It’s why he got the raise over me.

Behind me, I can feel Roland staring. He thinks I’m envying him. But you know what? I have nothing to envy. I’m in that picture too. Go ahead, if you look closely enough, in the opposite corner behind the director’s elbow, right there in the background, right where the caption starts you can see me behind the ‘–

IZED

’, hunched over my computer. The caption reads: ‘

PRIZED WORK COMING TO THE ART INSTITUTE. (FROM LEFT) DIRECTOR DAVID LANG, DONALD GENTRY, AND ROLAND PEROSKI

.’

‘It’s the first self-portrait he did after he lopped off his ear,’ Roland says, all high and mighty.

You can’t tell that from the painting. It’s a profile from the left. Van Gogh looks so sad. But at the same time, for someone who was so depressed he put a lot of colour into it. Bright specks of yellows, greens, reds and blues fill the painting. His hair is orange and his eyes a kryptonite-green. You can see the manic in them.

And here, Roland goes into bragging mode. He starts stroking the top of the canvas like it’s a cat. ‘The boss thinks this painting alone will attract an extra forty-thousand visitors in the next few months,’ he says. ‘So many museums wanted to get this piece, but none of them had the right connections. The real interesting thing is that…’

And I quickly lose interest. Lack of sleep makes my head feel so hollow my thoughts bound around the room like leaping sheep, before my eyes come to rest on his desk and the

Hollywood Reporter

with Penelope Cruz on the cover.

Maybe what I need right now is a pick-me-up. Maybe I can borrow the magazine and take a quick trip to the bathroom.

‘Hey, buddy? Jerry? Hello?’ Roland is saying. My thoughts snap back to him. He’s still standing by the painting, absentmindedly rubbing his finger over the top of the canvas. You can tell Roland’s an ex-Hollywood guy. He needs all the attention on him and his ‘accomplishments’. When he doesn’t have that, he’s one of those guys that fake concern that because you aren’t paying attention to him there must be something wrong with you. ‘Hey, buddy, you OK pal?’

And that’s when I think, fuck it, and decide to tell him about the

dream. He’s an artist after all. Maybe he knows what a silverware factory symbolises in dream-speak. But I might as well be talking to myself. Before I’ve hardly begun, Roland’s solely focused on the painting again, a short stroking of just the same one-inch section of the top of the canvas, as if he’s found an invisible pimple he’s considering popping.

The painting isn’t that big a deal

, I yell in my head.

In my head I say,

No one cares about fine art anymore

.

In my head I say,

You’re so full of yourself

.

So with Roland engrossed in his own glory, I edge over to his desk and take the

Hollywood Reporter

with Penelope Cruz and slowly roll it up and put it in my sleeve.

But with him stroking the canvas and me with my jerk material shoved up my sleeve, this is just getting awkward. So I say, ‘Hey, what’s with the camera crew outside?’

He says nothing.

I say, ‘Roland?’

And he says, ‘Oh, yeah – they’re doing some story on how the museum’s renovation is way over budget.’ Then, as if starting to snap out of his trance, he says, ‘Hey buddy, I should get started on this.’

And feeling the magazine rolled up in my shirtsleeve, I agree. I tell him I better get those Chagalls corrected, but he’s already shut the door behind me.

Back in the Grey Room I’m all alone. Donald is at his weekly ten a.m. with the museum board. That gives me the privacy to lock the door.

And a little after eleven I give Donald the colour-corrected TIFFs. I tell him I’m going to lunch. I need to get out of this grey prison.