Eugénie: The Empress & her Empire (27 page)

Read Eugénie: The Empress & her Empire Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

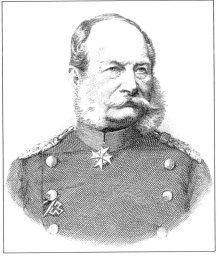

King William of Prussia (

Gothaischer genealogischer Hofkalender, 1871

)

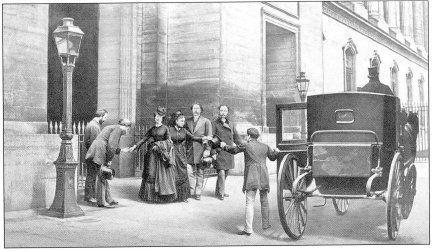

Eugénie’s escape in 1870, restaged by actors for the former court photographer Comte Aguado. Two, not five, men had been present. (

Author’s collection

)

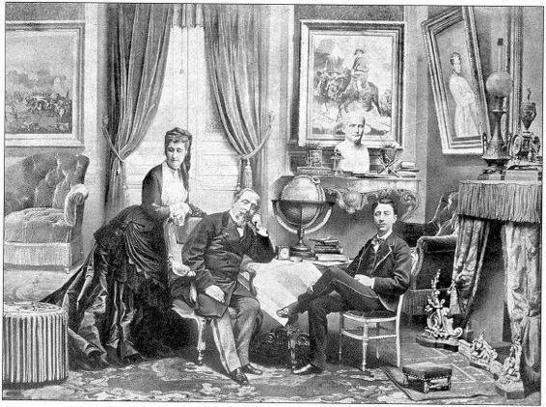

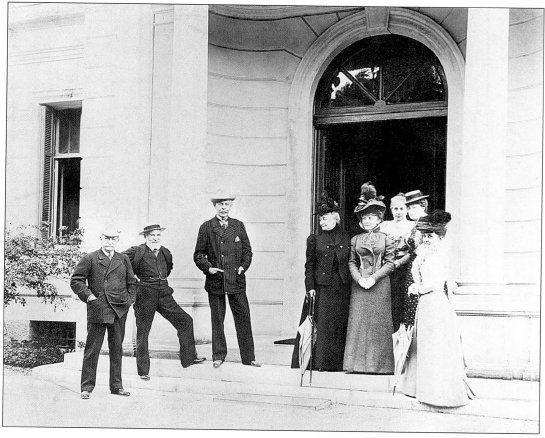

The imperial family in exile at Chislehurst, December 1872. This is the last known photograph of Napoleon III, who was planning another

coup d’état

. (

Private collection: AKG London

)

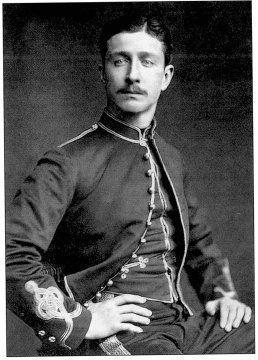

‘Napoleon IV’ at twenty-one, in British uniform, from a photo-graph of 1877. He is wearing the mess kit of the Royal Artillery. (

Author’s collection

)

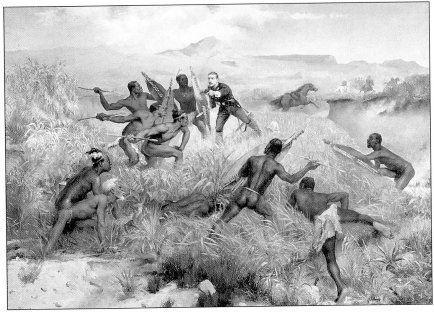

The death of the Prince Imperial in 1879 by Jamin. On the front of his body were found seventeen assegai wounds. (

Château de Compiègne: RMN – Jean Hutin

)

Eugénie’s court in exile about 1905 at Villa Cyrnos, from an unpublished photograph, with Augustin Filon on the extreme left, and Franceschini Pietri next to him. (

Collection of Dudley Heathcote

)

Carlotta forced her way into Saint-Cloud four times more. On the last occasion the emperor said that her husband should abdicate – he would be found another throne in the Balkans and all Europe would admire him for ‘sparing blood and tears’. She screamed, ‘blood and tears, they’re going to flow again and again because of you, in rivers of blood, all on your head’. When Eugénie offered her a glass of water, she threw it at her, howling, ‘Murderers, I won’t drink your poison.’

The Empress Carlotta then left for Rome, writing to Maximilian that Napoleon was really the devil in disguise. At Rome she told the pope that her ladies were trying to kill her and must be arrested. She had gone completely insane. Taken home to Belgium, she lived on, hopelessly mad, until 1927. The Emperor himself stayed in Mexico, refusing to abdicate or to leave the country, which, for the time being, was protected by French troops.

If Eugénie’s judgment failed her over Mexico, her husband was equally at fault. She was certainly telling the truth when she said that her concept of a Mexican empire had been largely inspired by a wish to bring benefits to a backward country. ‘We were misled,’ she claimed with reason, ‘We were told that the Mexican people would welcome the proclamation of a monarchy … several times – for example, after our troops entered Mexico city, after Bazaine’s victories in the northern provinces or after Maximilian’s warm reception at his capital – we had some cause to think that the expedition would be a success.’

Even so, as will be seen, sometimes she was shrewder than her husband.

During the 1860s European politics were bewilderingly complex, but an account of them cannot be omitted if one is to understand Eugénie. As she herself insisted, what really interested her were foreign affairs, and we know that from the very earliest days of her marriage, Napoleon III had been in the habit of discussing policy with her – although he did not always tell her everything that was in his mind. Gradually she became obsessed with international relations in Europe, far more than with the problems of Mexico. At the same time, when her husband’s health began to deteriorate he grew much readier to listen to her views and take her advice. Even if she was wrong about the Mexican empire, generally her instincts were excellent. No other woman of the nineteenth century possessed influence of this sort, on such a scale.

After the Crimean War was over, the emperor had tried, at first with reasonable success, to build closer relations with Russia, while attempting to keep on as good terms as he could with England. The new Russian emperor, Alexander II (the future liberator of the serfs), who was certainly a more imaginative and flexible man than his father Nicholas I had been, welcomed Napoleon’s overtures. During the Italian war of 1859 he alerted France to the danger of Prussian intervention, sending his personal aide-de-camp, Prince Schuvalov, to Paris to warn the emperor, and to some extent Prussia was deterred from attacking across the Rhine by nervousness about Russian intentions.

As has been seen, however, Eugénie’s dislike of the upheavals caused by the 1859 war, and her deepening friendship with the Metternichs, made her more and more inclined to see Austria and not Russia as France’s natural ally. This was by no means a new approach – it had always been the policy of King Louis-Philippe’s government and, during the Second Empire’s early years, of the foreign minister, Drouyn de Lhuys. Moreover, a fair number of very influential Austrians saw Russia as their greatest enemy.

What finally destroyed any likelihood of a lasting understanding between France and Russia was the sudden re-emergence of the insoluble Polish question. The Kingdom of Poland had disappeared during the infamous ‘partitions’ of the last quarter of the eighteenth century, Russia taking the bulk of the country, Austria the southwest and Prussia the north-west, a tripartite occupation that was renewed by the 1815 settlement. A rising by the Poles against the Russians in 1831 had failed, despite arousing sympathy throughout Europe.

From the very beginning, Napoleon III had wanted to help the Poles. They had fought heroically for his uncle, who, if the 1812 campaign had ended differently, would almost certainly have

restored their ancient kingdom. He had cursed the craven Louis-Philippe for not even protesting, let alone intervening, during the crushing of the 1831 rising.

By January 1863 when ‘one fine morning the bombshell of the Polish insurrection burst about our heads’, as Eugénie put it, the emperor’s sympathy had grown still deeper, in common with most western Europeans. Not only did liberals feel pity for an enslaved nation but Catholics were angry at the oppression of their co-religionists; in Montalembert’s words, ‘Since the murder of Poland all Europe has been in a state of mortal sin.’ Graphic reports of savage reprisals by the Russians caused widespread revulsion. The unequal struggle lasted for over a year, tens of thousands of Polish patriots being herded off in chains to Siberia.

In 1914 the empress discussed the insurrection with the diplomat Maurice Paléologue. All too often in

Entretiens de l’Impératrice Eugénie

,

*

Paléologue put his own opinions and even his own words into Eugénie’s mouth, sometimes altering what she had said to him (especially when it was about Kaiser Wilhelm II). Yet his account of her recollections of what happened in 1863 is convincing. Her mind retained all its clarity.

‘You cannot imagine the magnificent impression made by this people suddenly rising in defence of their religion and their nationhood’, she recalled. ‘Nothing so heroic had been seen since the Spaniards’ revolt against the French occupation … every church was a living centre of patriotism.’ She was thrilled by the way compassion for Poland united the French. ‘From republicans to Legitimists, from free-thinkers to clericals, from Jules Favre to Mgr Dupanloup, from the Faubourg Saint-Germain to the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, there arose the same cry of admiration for the Poles and of disgust with Russia.’ For the first time she found herself in complete agreement with Plon-Plon – ‘My ferocious enemy, Prince Napoleon’.

France, England and Austria sent notes to St Petersburg, advising Russia to give the Poles a constitution. The emperor assured a

Polish leader in Paris, Prince Adam Czartoryski, that he intended to send them guns and then an army – he was prepared to go to war if he could find allies.

A fortnight after the rising broke out, Bismarck (Prussia’s new minister-president) sent General von Alvensleben to sign an agreement with Russia allowing her troops to pursue ‘rebels’ over the Prussian border but declined a proposal by the tsar that Prussia and Russia should immediately declare war on France and Austria. Eugénie said that Bismarck’s motive was ‘separating France and Russia’, yet relations between them had already collapsed. When Napoleon complained to Berlin about its own ill treatment of the Poles the British wrongly suspected he was planning to attack Prussia and seize the Rhineland frontier – the emperor had no wish to fight both Prussia and Russia.

Prince Metternich reported a conversation he had with Eugénie at the Tuileries on 21 February 1863. Producing a map of Europe, she said she would like to fly over it with him so that they could get a bird’s eye view. (‘What a flight, and what a bird’, he joked in his dispatch.) She wanted to redraw the map, she told Metternich. She wished to see Poland restored under the king of Saxony, Russia being compensated at Turkey’s expense. Prussia would get Saxony and Hanover – surely something could be found in America for the Hanoverian king? Austria would cede Galicia to Poland and Venetia to Italy in return for Silesia, part of Germany south of the Main and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Italy would give up the Papal States and Naples. Constantinople would go to Greece. The empress admitted, without any embarrassment, that the scheme meant war with Prussia.