Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking (11 page)

Read Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking Online

Authors: Fuchsia Dunlop

Tags: #Cooking, #Regional & Ethnic, #Chinese

¾ tsp salt

1 tsp sugar

2 tbsp light soy sauce

2 tbsp chilli oil with its sediment

½ tsp sesame oil

Trim the radishes. Smack them lightly with the side of a cleaver or a rolling pin; the idea is to crack them open, not smash them to bits.

Add the salt and mix well. Set aside for 30 minutes.

Combine the sugar and soy sauce in a small bowl. Add the chilli and sesame oils.

When you are ready to eat, drain the radishes—which will have released a fair amount of water—and shake them dry. Pour the prepared sauce over them, mix well and serve.

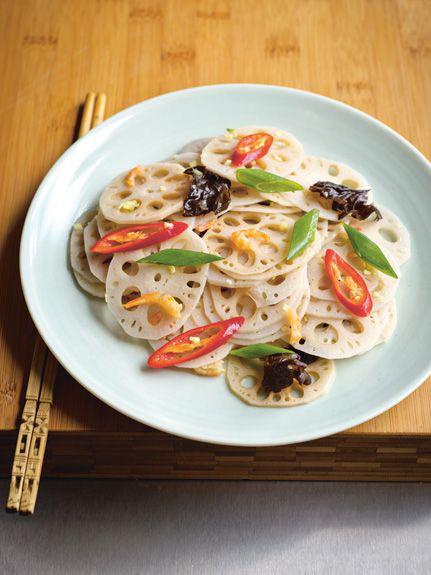

DELECTABLE LOTUS ROOT SALAD

MEI WEI OU PIAN

美味藕片

The so-called “root” of the lotus is actually the underwater stem of the waterlily. Other parts of the plant can also be eaten: the seeds, a traditional symbol of fertility, are made into soups and sweetmeats; the thin flower stems are delicious stir-fried; the broad lily leaves are used to wrap meat or poultry for an aromatic steaming, or a mud-baked “beggar’s chicken”; I’ve even tasted the delicate white waterlilies themselves, in a lyrical soup of assorted water plants. The root, cut into slices, has an ethereal quality, with its crisp, crystalline flesh and snowflake pattern of holes, which this colorful salad shows off beautifully.

1 tbsp dried shrimp (optional)

A couple of small crinkly pieces of dried wood ear mushroom

1 section of fresh young lotus root (about 7 oz/200g)

1 tsp finely chopped ginger

2½ tsp clear rice vinegar

1 tsp sugar

A few small horse-ear (diagonal) slices of red chilli or bell pepper, for color

1 spring onion, green part only, sliced diagonally

1 tsp sesame oil

Salt, to taste

Soak the dried shrimp (if using) and the wood ears, separately, in hot water from the kettle for at least 30 minutes.

Bring a panful of water to a boil. Break the lotus root into segments and use a potato peeler to peel them. Trim off the ends of each segment and slice thinly and evenly: each slice will have a beautiful pattern of holes.

Blanch the lotus root slices in the boiling water for a minute or two; they will remain crisp. (Make sure you blanch them soon after cutting, or the slices will begin to discolor.) Refresh in cold water and drain well.

Drain the wood ears and the shrimp (if using). Tear the wood ears into small pieces.

Combine all the ingredients together in a bowl and mix well.

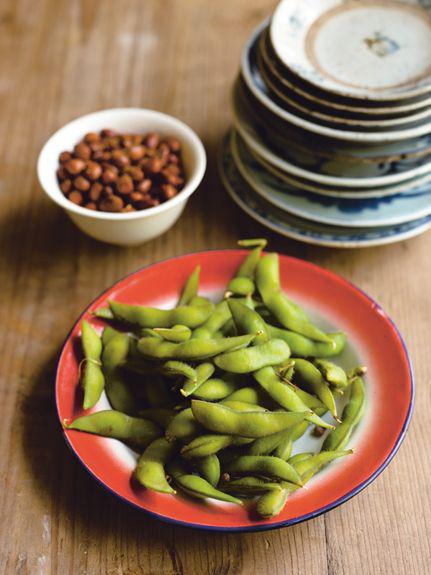

GREEN SOY BEANS, SERVED IN THE POD

MAO DOU 毛豆

Young green soy beans, served in the pod, have become popular in Japanese restaurants in the West, which is why they are often known by their Japanese name, edamame. They are also a favorite snack in Sichuan, where they might be offered with beer, alongside salted duck eggs, peanuts and aromatic cold meats. In Chinese, they are known as

mao dou

, “hairy beans,” because of the furry skins of their pods.

Salt

One ½ oz (20g) piece of ginger, unpeeled

A few pinches of whole Sichuan pepper

About 11 oz (300g) frozen soy beans in their pods

Bring a panful of water to a boil and add salt. Crush the ginger slightly with the flat of a cleaver blade or a rolling pin and add to the pan with the Sichuan pepper and the beans.

Return to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for about five minutes. Drain well and serve at room temperature.

Invite your guests to squeeze the beans from the pods and eat them. The furry pods should be discarded.

The Chinese have, throughout history, shown a remarkable preference for selecting and cultivating the most nutritious food plants available to them. The soy bean, which has been grown in China for more than three millennia, is richer in protein than any other plant food. It contains all the amino acids essential for human health, in the right proportions. Along with rice and leafy greens, it is one of the cornerstones of the largely vegetarian traditional diet. Young green soy beans are eaten fresh, as a vegetable, but far more important are the dried beans, which are transformed through ancient technologies into fermented seasonings and tofu.

Tofu is formed by soaking dried soy beans in water, grinding them with fresh water to give soy milk, straining out the solid residue of the beans, then heating the milk and adding a coagulant to set the curds. The set curds may be eaten as they are, or pressed to rid them of excess water and make them firmer. Tofu-making is a process that has been known in China since at least the tenth century AD, although legend traces its invention back further, to the second century king, Liu An.

Some Westerners still seem to think of tofu as some sackcloth-and-ashes sustenance for vegans, and a sad substitute for meat. In China, however, it is one of the most ubiquitous foodstuffs and wonderful when you acquire a taste for it. In its most basic form it may be plain, but then so is ricotta cheese; tofu is so gentle and innocent, so richly nutritious, so kind to earth and conscience. And of course, as a vehicle for flavor, it’s amazing. No one could accuse a Sichuanese Pock-marked Old Woman’s Tofu of being insipid; in my experience even avid meat-eaters enjoy it. And who could resist the juicy charms of a Cantonese Pipa Tofu? (You’ll find both recipes in this chapter.)

Plain tofu is only one of the myriad forms of this shape-shifting food. The unpressed curd, known as “silken” tofu or bean “flower,” has the delightful, slippy texture of pannacotta. Eaten with a spoon, it is perfect comfort food. Just thinking about Sichuanese Sour-and-hot Silken Tofu—with its zesty dressing of pickles, soy sauce, chilli and crunchy nuts—makes my mouth water.

Plain white tofu can be deep-fried into golden puffs, or pressed into blocks or sheets as thin as leather. After pressing, this “firm” tofu can be simmered in a spiced broth or smoked over wood embers to give it a wonderful flavor. Stir-fry it with a fresh vegetable such as celery or chives, serve it with rice and you have a very satisfying supper. And for high cheesy tastes, look no further than fermented tofu, a magical cooking ingredient and a stupendous relish that is utterly addictive. Add some to a wokful of stir-fried spinach and you’ll see what I mean.

Some 300 years ago, the Qing Dynasty poet and gourmet Yuan Mei lampooned those who were impressed by ostentatious delicacies, writing that a well-cooked dish of tofu, humble though it might be, was far superior in taste to a bowlful of expensive bird’s nest. I hope, when you try some of these recipes, that you’ll agree.

Some tips on using tofu

– Blanch plain white tofu in hot salted water before use, to freshen up its flavor and warm it before you combine it with other ingredients.

– When adding seasonings to simmering white tofu in a broth or sauce, to avoid breaking up the pieces of tofu, simply push them gently with the back of your wok scoop or ladle to allow the ingredients to mingle, rather than stirring.

– Don’t let tofu boil vigorously for too long unless you want it to become porous and slightly spongey in texture.

– Freezing tofu changes its texture completely: the formation of water crystals creates a honeycomb of holes, so the thawed tofu has a chewy, spongey texture. Northern cooks do this deliberately, because the thawed tofu absorbs the flavors of sauces rather beautifully; but don’t try it if you want a tender mouthfeel.

– Cover any leftovers of fresh white tofu in water, store them in the refrigerator, and use within a couple of days.

A note on names

English speakers may refer to tofu as beancurd or bean curd. Tofu is overwhelmingly the most widely known word for this foodstuff, which is why I have chosen to use it in this book.

POCK-MARKED OLD WOMAN’S TOFU (VEGETARIAN VERSION)

MA PO DOU FU

麻婆豆腐

Mapo doufu

is one of the best-loved dishes of the Sichuanese capital, Chengdu. It is named after the wife of a Qing Dynasty restaurateur who delighted passing laborers with her hearty braised tofu, cooked up at her restaurant by the Bridge of 10,000 Blessings in the north of the city. The dish is thought to date back to the late nineteenth century. Mrs. Chen’s face was marked with smallpox scars, so she was given the affectionate nickname

ma po

, “Pock-marked Old Woman.”

The dish is traditionally made with ground beef, although many cooks now use pork. This vegetarian version is equally sumptuous. Vegetarians find it addictive: one friend of mine has been cooking it every week since I first taught her the recipe some 10 years ago. In Sichuan, they use garlic leaves (

suan miao

) rather than baby leeks, but as they are hard to find, tender young leeks make a good substitute, as do spring onion greens. You can also use the green sprouts that emerge from onions or garlic bulbs if you forget about them for a while (as I often do). This dish is best made with the tenderest tofu that will hold its shape when cut into cubes.

1–1¼ lb (500–600g) plain white tofu

Salt

4 baby leeks or spring onions, green parts only

4 tbsp cooking oil

2½ tbsp Sichuan chilli bean paste

1 tbsp fermented black beans, rinsed and drained

2 tsp ground red chillies (optional)

1 tbsp finely chopped ginger

1 tbsp finely chopped garlic

½ cup (100ml) vegetarian stock or water

¼ tsp ground white pepper

2 tsp potato flour mixed with

2 tbsp cold water

¼–½ tsp ground roasted Sichuan pepper

Cut the tofu into ¾ in (2cm) cubes and leave to steep in very hot, lightly salted water while you prepare the other ingredients (do not allow the water to boil or the tofu will become porous and less tender). Slice the baby leeks or spring onion greens at a steep angle into thin “horse ears.”

Heat a wok over a high flame. Pour in the cooking oil and swirl it around. Reduce the heat to medium, add the chilli bean paste and stir-fry until the oil is a rich red color and smells delicious. Next add the black beans and ground chillies (if using) and stir-fry for a few seconds more until you can smell them too. Then do the same with the ginger and garlic. Take care not to overheat the seasonings; you want a thick, fragrant sauce and the secret of this is to let them sizzle gently, allowing the oil to coax out their flavors and aromas.