Read Everything Bad Is Good for You Online

Authors: Steven Johnson

Everything Bad Is Good for You (21 page)

So if Dickens could juggle Great Art and Mass Audience, why should we tolerate some of the lesser creatures that populate the high end of the Nielsen ratings today? The answer, I believe, is that the definition of a “mass success” has changed since Dickens's time. On average, Dickens sold around 50,000 copies of the serialized versions of his novels, during a time in which the British population was roughly 20 million. Had Dickens's potential audience been the size of the United States todayâ280 million peopleâhe would have sold something like 800,000 copies of his first-run novels. The most innovative shows on television today

âThe West Wing, 24, The Simpsons, The Sopranosâ

often attract between 10 and 15

million

viewers. So by this measure,

West Wing

is roughly twenty times more “mass” than Dickens was, even though Dickens had no mass media rivals for his audience's attentionâno television or radio or cinema to compete with. It's no wonder Dickens was able to persuade his readers to keep up with his rhetorical innovations. In his day, Dickens had the per capita audience that would today tune in for a Masterpiece Theatre airing of

Bleak House.

His audience was mass by Victorian standards; no genuinely literary author had attracted that many readers before. But by modern standards, he was writing for the elite.

Dickens may not have been a mass author by modern standards, but you needn't look far to find an example of truly mass cultural successes that are simultaneously the most complex and nuanced in their field. Violent video games like

Quake

or

Doom

tend to dominate the mainstream media discussion of gaming, but the fact is the shooter games are rarities on the gaming best-seller lists. The two genres that historically have dominated the charts are both forms of complex simulation: either sport sims, or GOD games like

SimCity

or

Age of Empires.

The most popular game of all time is the domestic saga

The Sims.

(The closest thing you'll see to a violent exchange in

The Sims

is when one of your virtual characters can't pay the monthly bills.) The sports simulations have reached a level of intricacy that makes the dice-baseball games I explored as a child look like tic-tac-toeânot just in their near-photorealistic graphics, but in the player's ability to control and model the most microscopic aspect of the game. Sega's

2K3

baseball simulator gives you an entire organization to general manage: trading players, nurturing minor leaguers, negotiating salaries and free agents. (This is not, incidentally, a universe of pure numbers. Emotions factor as well. Bench a highly paid prima donna for a few days, and his productivity will diminish, just as it will on the real-world diamond.) As for the social and historical simulations, just think back to my nephew learning about the effects of industrial taxes while playing

SimCity.

The violent games may generate the most outrage, but the games that people reliably line up to buy are the ones that require the most thinking. Somehow in this age of attention deficit disorder and instant gratification, in this age of gratuitous violence and cheap titillation, the most intellectually challenging titles are also the most popular. And they're growing more challenging with each passing year.

Â

S

O THIS

is the landscape of the Sleeper Curve. Games that force us to probe and telescope. Television shows that require the mind to fill in the blanks, or exercise its emotional intelligence. Software that makes us sit forward, not lean back. But if the long-term trend in pop culture is toward increased complexity, is there any evidence that our brains are reflecting that change? If mass media is supplying an increasingly rigorous mental workout, is there any empirical data that shows our cognitive muscles growing in response?

In a word: yes.

ART

T

WO

And Nietzsche, with his theory of eternal recurrence. He said that the life we lived we're going to live over again the exact same way for eternity. Great. That means I'll have to sit through the Ice Capades again.

âW

OODY

A

LLEN

Â

I

N THE LATE SEVENTIES,

an American philosopher and longtime civil-rights activist named James Flynn began investigating the history of IQ scores, in an attempt to refute studies published by controversial scholar Arthur Jensen, whose work later influenced the even more controversial book

The Bell Curve.

Jensen's research had uncovered an alleged gap between white and black IQ scores, a gap that wasn't attributable to differences in education or economic upbringing. Despite his lack of professional training in the field, Flynn decided to throw himself into the fray and prove that IQ tests were more culturally biased than Jensen had believed, thus making the racial IQ gap a byproduct of history not biology. Flynn's investigation led him to military records that clearly showed a dramatic increase in African-American IQ scores over the past half century, a trend that initially seemed to support his argument against Jensen: As African-Americans were granted greater access to the educational system, their IQ scores improved accordingly.

But as Flynn sifted through the data, he found something that challenged his expectations. Black scores were rising, to be sure. But white scores were rising almost as fast. Across the board, irrespective of class or race or education, Americans were getting smarter. Flynn was able to quantify the shift: in forty-six years, the American people had gained 13.8 IQ points on average.

The trend had gone unnoticed for so long because the IQ establishment routinely normalized the exams to ensure that a person of average intelligence scored 100 on the test. So every few years, they'd review the numbers and tweak the test to ensure that the median score was 100. Without realizing it, they were slowly but reliably increasing the difficulty of the test, as though they were ramping up the speed of a treadmill. If you looked exclusively at the history of the scores themselves, IQ seemed to be running in place, unchanged over the past century. But if you factored in the mounting challenge presented by the tests themselves, the picture changed dramatically: the test-takers were getting smarter.

Many of you may hold the opinion that IQ has been debunked by recent developments in brain science and sociology, and to a certain extent it has. That debunking has taken two primary forms: IQ has been shown to be more vulnerable to environmental conditions than its original “innate intelligence” billing indicated; and the intelligence that the IQ tests measure has been shown to reflect only part of the spectrum of human intelligence. But those objectionsâtrue as they may beâdo not undermine the trend described by the Flynn Effect in any way. In fact, they may make it more interesting.

Clearly there are multiple forms of intelligence, only some of which are measured by IQ tests: emotional intelligence, for one, is entirely ignored by all traditional IQ metrics. And the Flynn Effect offers what many consider incontrovertible evidence that IQ is profoundly shaped by environment, since genetics alone can't explain such a dramatic rise in such a short amount of time. So when critics object to the practice of comparing individual or group IQsâas in

The Bell Curve

's observation that African-Americans have, on average, lower IQs than those of white Americansâtheir objections have real merit: because IQ isn't the only gauge of real-world intelligence, and because differences in IQ may be due largely to environmental factors. Thus, IQ scores are less relevant in comparing the intelligence of, say, different ethnic groupsâor even different candidates for college admission.

So why are IQ scores relevant to the Sleeper Curve? Because differences

between

generations don't pose the same problems that differences

within

generations do. When you look at a snapshot of black and white IQ tests from 1975, explaining the difference between those scores is a necessarily murky affair: each group possesses different combinations of genes

and

different environments. But when you look at IQ scores across generations, the picture gets clearer. Whatever genetic differences may exist between groups disappear, because you're looking at the average IQ of the entire society. The gene pool hasn't changed in a generation, and yet the scores have gone up. Some environmental factor (or combination of factors) must be responsible for the increase in the specific forms of intelligence that IQ measures: problem solving, abstract reasoning, pattern recognition, spatial logic.

Psychologists and social scientists and other experts in psychometrics have now had twenty years to study the Flynn Effect; while much debate remains about the ultimate causes behind the IQ increase, the existence of the trend itself is uncontested. IQs have been rising in most developed countries at an extraordinary clip over the past century: an average of 3 points per decade. A number of studies have suggested that the rate of increase is itself accelerating: average scores in the Netherlands, for instance, increased 8 points between 1972 and 1982. A few points may not sound like much, but the numbers quickly add up. Imagine this scenario: a person who tests in the top 10 percent of the United States in 1920 time-travels eighty years into the future and takes the test again. Thanks to the Flynn Effect, he would be in the bottom third for IQ scores today. Yesterday's brainiac is today's simpleton.

A small part of the Flynn Effect may be attributable to increased familiarity with intelligence tests themselves. But as Flynn points out, even if you take the exact same IQ test multiple times in a row, the benefits from that repeat exposure cap out at around 5 or 6 points. And the heyday of IQ testing was the middle of the twentieth century. Over the past thirty years, the rise in IQ scores has been accelerating, even as the administration of IQ tests has become less common.

Nor is the Flynn Effect likely to be the product of better nutrition. Adult height is famously sensitive to early diet, and indeed average heights have been on the rise for most of the past two centuries in the industrialized world. But in the United States and Europe the trend toward increased height leveled in the decades after World War II, presumably corresponding to a leveling off in the trend toward improved childhood nutrition. And yet the postwar period shows the most dramatic spike in IQ. If better nutrition were sharpening our brains, we would expect to see height increases running parallel to IQ increases. We would also expect to see improvements across the board in mental function, and not just the logic tests of IQ. But on tests that measure skills specifically taught in the classroomâmath or historyâU.S. students have been flatlining or worse for much of the past forty years. This suggests that improved education cannot be responsible for the Flynn Effect. For decades now, the recurring story about the U.S. educational system has long been its lagging test scores, numbers that are cited again and again whenever critics rail against failing public schools. They're right to complain, because those indices do measure skills that are important in real-world success, for both the individual and the society. But beneath those sorry numbers, a strangely encouraging trend continues: Where pure problem-solving is concerned, we're getting smarter.

If we're not getting these cognitive upgrades from our diets or our classrooms, where are they coming from? The answer should be self-evident by now. It's not the change in our nutritional diet that's making us smarter, it's the change in our

mental

diet. Think of the cognitive laborâand playâthat your average ten-year-old would have experienced outside of school a hundred years ago: reading books when they were available, playing with simple toys, improvising neighborhood games like stickball and kick the can, and most of all doing household choresâor even working as a child-laborer. Compare that to the cultural and technological mastery of a ten-year-old today: following dozens of professional sports teams; shifting effortlessly from phone to IM to e-mail in communicating with friends; probing and telescoping through immense virtual worlds; adopting and troubleshooting new media technologies without flinching. Thanks to improved standards of living, these kids also have more time for these diversions than their ancestors did three generations before. Their classrooms may be overcrowded and their teachers underpaid, but in the world outside of school, their brains are being challenged at every turn by new forms of media and technology that cultivate sophisticated problem-solving skills.

Practically every family with young children has a running gag about how little Junior knows how to program the VCR while Mom and Dad with their advanced degrees can barely set the alarm clock. But I suspect we're too quick to write these skills off as mere superficial technical knowledge. The ability to take in a complex system and learn its rules on the fly is a talent with great real-world applicability; just like learning to read a chessboard, the content of the skill isn't as important as the general principles that underlie it. When your ten-year-old figures out how to consolidate all seven remote controls into a single unit, she's exercising problem-solving muscles with an insistence that rivals anything she's learning at school. You want your children fixing your home theater setup, not because they'll be able to use that skill working for Circuit City one day, but rather because there's a commendable structure to this kind of thinking.

The social psychologist Carmi Schooler sees the Flynn Effect as a reflection of environmental complexity:

The complexity of an individual's environment is defined by its stimulus and demand characteristics. The more diverse the stimuli, the greater the number of decisions required, the greater the number of considerations to be taken into account in making these decisions, and the more ill-defined and apparently contradictory the contingencies, the more complex the environment. To the degree that such an environment rewards cognitive effort, individuals should be motivated to develop their intellectual capacities and to generalize the resulting cognitive processes to other situations.

Environmental complexity is not limited to media, of course, but the characteristics that Schooler outlines describe precisely the contours of the Sleeper Curve: first, the emergence of mediaâlike games and other interactive formsâthat force decision-making at every turn; the increase in social and narrative complexity evident in television and some film; the intoxicating rewards of popular entertainment. All these forces working together create an environment likely to enhance problem-solving skills. Other forms of modern complexity may also be a factor here, of course: urban environments are, by Schooler's definition, more complex than rural ones, and so the industrial-age migration to the cities may play a role in the Flynn Effect. But most of the industrialized world underwent that migration before World War II; the post-war trend has been surburban flight. And so the most dramatic spike in IQ scoresâthe one witnessed over the past thirty yearsâis most likely being driven by something else.

Â

T

HE LINK

between the Flynn Effect and popular media is a hypothesis, but there are a number of reasons to think that more than a casual connection exists. As research into the Flynn Effect has deepened, three important tendencies have come to light, all of which parallel the developments in popular culture I've described over the preceding pages. The first is the general pattern itself: higher IQs mirroring the increased complexity of the culture. But in exploring the specifics of those IQ scores, researchers discovered a second trend in the data: the historical increase grew more dramatic the further the tests ventured from skillsâlike mathematic or verbal aptitudeâthat reflect educational background. The Flynn Effect is most pronounced on tests that assess what psychometricians call

g,

the index that offers the best approximation of “fluid” intelligence. Tests that measure

g

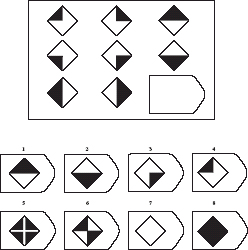

often do away with words and numbers, replacing them with questions that rely exclusively on images, testing the subject's ability to see patterns and complete sequences with elemental shapes and objects, as in this example from the Raven Progressive Matrices test, which asks you to fill the blank space with the correct shape from the eight options below:

The centrality of the

g

scores to the Flynn Effect is telling. If you look at intelligence tests that track skills influenced by the classroomâthe Wechsler vocabulary or arithmetic tests, for instanceâthe intelligence boom fades from view; SAT scores have fluctuated erratically over the past decades. But if you look solely at unschooled problem-solving and pattern-recognition skills, the progressive trend jumps into focus. There's something mysterious in these simultaneous trends: if

g

exists in a cultural vacuum, how can scores be rising at such a clip? And more puzzling, how can those scores be rising faster than other intelligence measures that do reflect education? The mystery disappears if you assume that these general problem-solving skills

are

influenced by culture, just not the part of culture that we conventionally associate with making people smarter. Their problem-solving skills are the result of the conditioning they get from interacting with popular culture that has grown more challenging over time. When you spend your leisure time interacting with media and technology that forces you to “fill in” and “lean forward,” you're developing skills that will ultimately translate into higher

g

scores. (For those of you curious about your own skills, the correct answer to the Raven test question above is 8.)