Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (43 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

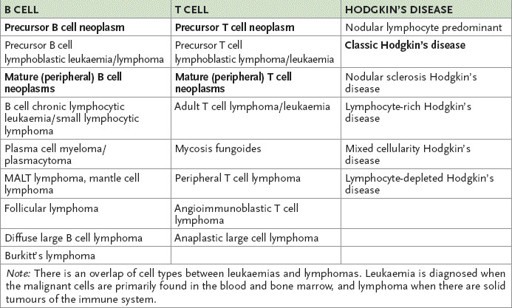

Table 8.12

World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphomas (lymphoid malignancies) – more common types

MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

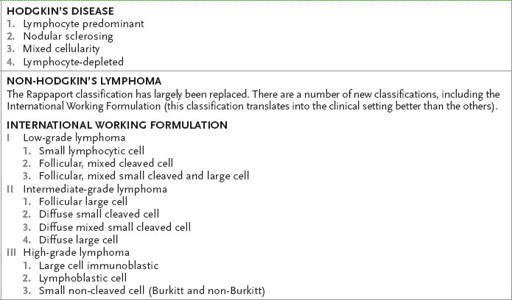

Table 8.13

Histopathological classification of lymphoma

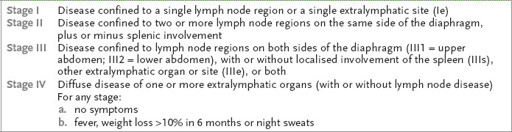

Table 8.14

Staging of lymphoma – Ann Arbor classification

Hodgkin’s disease (see

Table 8.13

) presents either with discrete, rubbery, painless nodes or with generalised symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss and sometimes pruritus). Mediastinal adenopathy usually occurs in young people with nodular sclerosing disease. Older people with generalised symptoms, in whom the only enlarged nodes may be in the abdomen, often have lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin’s disease.

The majority of cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (see

Table 8.13

) present with painless enlargement of peripheral lymph nodes (a lymph node of >1 cm diameter that has been present for 6 weeks or more for no obvious reason should be biopsied). The great majority of patients with peripheral lymph node enlargement do not have a malignancy. Localised or generalised painless adenopathy with or without hepatosplenomegaly may also occur. It may present with just an abdominal mass. Presentation with mediastinal adenopathy is much less common than in patients with Hodgkin’s disease (except in T lymphoblastic lymphoma and primary mediastinal B large cell lymphoma where mediastinal disease is always present). In some patients the disease may arise at an extranodal site (e.g. the gastrointestinal tract – 5%). These patients may present with abdominal pain, obstruction or haemorrhage.

Most non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are diffuse and aggressive. Waldeyer’s ring, mesenteric and epitrochlear node involvement are more common in non-Hodgkin’s than in Hodgkin’s disease. Systemic symptoms are less common in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lymphadenopathy has often been present for a long time.

Other uncommon presentations include skin infiltration and direct renal infiltration. Primary neurological infiltration is also uncommon. Low-grade gastrointestinal lymphomas (e.g. MALT – mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue – lymphomas) are less common.

The history

1.

Ask about the presenting symptoms and causes of symptoms, such as palpable nodes, cough as a result of mediastinal node involvement, systemic symptoms, bone pain owing to marrow infiltration or pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, splenic pain and alcohol-induced pain (rare).

2.

Is there a history of infection (as a result of decreased cell-mediated immunity in Hodgkin’s disease or depressed humoral immunity from chemotherapy or radiotherapy)?

3.

Ask about the history of the predisposing condition, such as Klinefelter’s syndrome, HIV infection, congenital or acquired immune deficiency, use of immunosuppressive drugs or autoimmune disease (e.g. Sjögren’s syndrome). Ask also about the use of phenytoin (pseudo-lymphoma).

4.

Find out the investigations performed – particularly lymph node biopsy, CT and gallium scans, and bilateral bone marrow aspirations. MRI scanning may have been used for suspected spinal cord, brain or bone marrow involvement. Lymphangiography and staging laparotomy are rarely indicated now. Lumbar puncture is important in high-grade lymphoma investigation if central nervous system involvement is suspected.

5.

Ask about the treatment undertaken, as this gives an indication of the stage and type of disease. Ask about the side-effects of any treatment (e.g. mantle radiation can result in pneumonitis, hypothyroidism, pericarditis, myocardial fibrosis and spinal cord injury). Ask whether the patient has been informed about possible long-term complications of treatment.

6.

Determine the prognosis given and what the patient’s understanding of this seems to be.

7.

Find out about the patient’s social situation – dependent family members, social support, ability to work, reactions to disease (e.g. depression, coping mechanisms), etc. As for other malignancies, work out the ECOG (Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group) performance status (

Table 8.15

).

Table 8.15

ECOG performance status

| GRADE | ECOG PERFORMANCE STATUS |

| 0 | Fully active; no restriction on activities compared with before the disease |

| 1 | Restricted, but only from strenuous activity. Able to perform light or sedentary work |

| 2 | Able to look after self. Mobile but not able to work |

| 3 | Only partly able to look after self. In bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours |

| 4 | Completely confined to bed or chair. Unable to look after self at all |

The examination

1.

Examine the haemopoietic system thoroughly. Particularly note any lymph nodes (

Fig 8.2

) and assess carefully for splenomegaly.

FIGURE 8.2

Cervical lymphadenopathy. J W Little, D A Falace, C S Miller, N L Rhodus,

Dental management of the medically compromised patient

, 7th edn. Fig 24-6. Mosby, Elsevier, 2008, with permission.

2.

Attempt to stage the disease clinically (

Table 8.14

). Remember that staging is much less relevant for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas because spread is haematogenous and not contiguous. Fewer than 10% of even nodular non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are localised and suitable for local irradiation at the time of presentation.

3.

Note any radiotherapy marks (and the field covered).

4.

Look for evidence of infection (e.g. herpes zoster).

5.

If the patient is clinically anaemic, consider a Coombs’ positive autoimmune process in your differential.

6.

Assess for any evidence of the hyperviscosity syndrome (Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia secondary to a monoclonal gammaglobulin): look in the fundi.

Investigations

Investigations are aimed at determining the grade and stage of the disease.

1.

The first step is to obtain histological confirmation of disease. Ask to see the pathology report if excision lymph node biopsies have already been performed. Fine-needle biopsy is not good enough to define lymph node architecture. Reed-Sternberg cells are

not

pathognomonic of Hodgkin’s disease, but may occur in cases of glandular fever, other viral diseases and with other malignancies.

2.

The next step is to stage the disease further.

a.

Ask for a full blood count and ESR, a bilateral bone marrow aspirate and trephine, liver function tests, and abdominal, pelvic and chest imaging (usually chest X-ray (

Fig 8.3

) followed by CT scan).

FIGURE 8.3

Chest X-ray showing bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (arrows). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

b.

If there is a major leukaemic component, order flow cytometry of the peripheral lymphocytes to aid in the diagnosis.

3.

In Hodgkin’s disease, agranulocytosis (sometimes with marked eosinophilia or a leukaemoid reaction), an elevated ESR, reversed CD4/CD8 ratio, skin test anergy and a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase level are often present, but may

not

indicate widespread disease. The ESR remains the best indicator of disease activity. Lymphangiography is less often done these days, especially if the CT, single-photon emission CT (SPECT) and gallium scans are normal. PET scanning may be more sensitive than gallium scanning in staging the disease at diagnosis and in monitoring residual disease. Staging laparotomies are now only rarely performed, but previously treated patients may bear the scar. Staging in this invasive way is less relevant now that systemic treatment is more often used for all patients. Always re-stage after treatment!

Treatment

HODGKIN’S DISEASE (85% OF PATIENTS ARE CURABLE)

Treatment depends on the stage of the disease (see

Table 8.14

). Histological type is less important.

•

Stages IA, IIA and IIIsA – radiotherapy or abbreviated course of chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy.

•

Stage IIIA (with para-aortic node involvement with or without radiotherapy to involved sites), IIIB and IV – combined chemotherapy (e.g. ABVD – adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine).

Salvage treatment

Relapse less than 1 year after initial treatment or failure to achieve complete remission is an indication for second-line therapy. For relapse after more than 1 year, retreatment can be given using the original regimen. Further radiotherapy can be used for relapse outside the radiation field if the patient has early stage disease. Autologous stem cell transplant after high-dose chemotherapy is an alternative.