Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (66 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

The history

1.

Ask about the chronological development of symptoms. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms should be sought (e.g. subphrenic abscess, diverticular abscess, cholangitis, appendiceal abscess, liver abscess, Crohn’s disease, metastatic cancer in the abdomen, Whipple’s disease). Note any preceding acute infections (e.g. diarrhoeal illness, boils).

a.

Chest pain may suggest pericarditis, multiple pulmonary emboli or, rarely, intraluminal dissection of the aorta.

b.

Joint pain may suggest rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, vasculitis, atrial myxoma or endocarditis.

c.

Dysuria or rectal pain may indicate prostatic abscess or urinary tract infection.

d.

Headache and joint or muscle pain may indicate giant cell arteritis.

e.

Night sweats may indicate lymphoma, tuberculosis, brucellosis, endocarditis or an abscess.

2.

Ask about place of residence and overseas travel (e.g. malaria, amoebiasis, fungal infections).

3.

Ask about contact with domestic or wild animals or birds (e.g. psittacosis, brucellosis, Q fever, histoplasmosis, leptospirosis, toxoplasmosis).

4.

Ask about close contact with persons who have tuberculosis.

5.

Enquire about occupation and hobbies – veterinary surgeon, farming (fungal infection, raw milk ingestion, hypersensitivity pneumonitis), intravenous drug use (contaminants e.g. quinine).

6.

Enquire about sexual practices (e.g. risk of HIV infection, sexually transmitted disease, pelvic inflammatory disease).

7.

Ask about evidence of immunocompromised host (e.g. cytomegalovirus,

Pneumocystis jirovecii

).

8.

Find out about medication used – drug fever (antibiotic allergy, e.g. sulfonylureas, penicillin), arsenicals, iodides, thiouracils, antihistamines, NSAIDs, antihypertensives (methyldopa, hydralazine), antiarrhythmics (procainamide, quinidine).

9.

Ask about anticoagulant use (accumulation of old blood in a closed space, e.g. retroperitoneal, perisplenic).

10.

Ask about iatrogenic infection (e.g. catheter, arteriovenous fistula, prosthetic heart valve).

11.

Ask about factitious fever from injection of contaminated material or tampering with thermometer readings – suspect the former diagnosis if there is an excessively high temperature or the latter in the absence of tachycardia, chills or sweats; this is more common in medical or paramedical personnel.

The examination

1.

Look at the temperature chart, if available, to see whether the fever pattern is characteristic. The temperature tends to fall to normal each day in pyogenic infections, tuberculosis and lymphoma, whereas in malaria the temperature can return to normal for days before rising again.

2.

Inspect the patient: note whether he or she appears ill or not, whether there is cachexia (suggesting a chronic disease process) and any skin rash (e.g. erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, adult Still’s disease (salmon-pink macular rash)).

3.

Pick up the hands and look for stigmata of infective endocarditis or any vasculitic changes, and for finger clubbing.

4.

Inspect the arms for injection sites (intravenous drug abuse).

5.

Palpate for epitrochlear and axillary lymphadenopathy (e.g. lymphoma, solid tumour spread, focal infections).

6.

Examine the eyes for iritis or conjunctivitis (e.g. connective tissue disease, sarcoidosis) or jaundice (e.g. cholangitis, liver abscess). Look in the fundi for choroidal tubercles (miliary tuberculosis), Roth’s spots (infective endocarditis), retinal haemorrhages or infiltrates (e.g. leukaemia). Note any facial rash (e.g. SLE). Feel the temporal arteries (temporal arteritis).

7.

Examine the mouth for ulcers and gum disease and the teeth and tonsils for infection. Feel the parotids for parotitis and the sinuses for sinusitis.

8.

Palpate the cervical lymph nodes.

9.

Examine for thyroid enlargement and tenderness (subacute thyroiditis).

10.

Examine the chest. Palpate for bony tenderness over the sternum and shoulders.

11.

Examine the respiratory system (e.g. for signs of tuberculosis, abscess, empyema, carcinoma) and the heart for murmurs (e.g. infective endocarditis, atrial myxoma) or prosthetic heart sounds or rubs (e.g. pericarditis).

12.

Examine the abdomen. Inspect for skin rash (e.g. the rose-coloured spots of typhoid (an uncommon long case)). Palpate for tenderness (e.g. abscess), hepatomegaly (e.g. granulomatous hepatitis, hepatoma, cirrhosis, metastatic deposits), splenomegaly (e.g. haemopoietic malignancy, infective endocarditis, malaria), renal enlargement (e.g. obstruction, renal cell carcinoma).

13.

Feel the testes for enlargement (e.g. seminoma, tuberculosis). Feel for inguinal adenopathy. Always ask for the results of the rectal examination (e.g. prostatic abscess, rectal cancer, Crohn’s disease) and pelvic examination (pelvic pus). Look at the penis and scrotum for a discharge or rash.

14.

Finally, examine the nervous system for signs of meningism (chronic meningitis) or focal neurological signs (e.g. brain abscess, mononeuritis multiplex in polyarteritis nodosa). Check the results of the urine analysis.

Investigations

1.

Determine how many blood cultures have been obtained and the results. Ask to review the blood count and smear (e.g. for neutropenia, eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytes), liver function tests, electrolytes and creatinine. Look at the chest X-ray. Rule out urinary tract disease if suspected.

2.

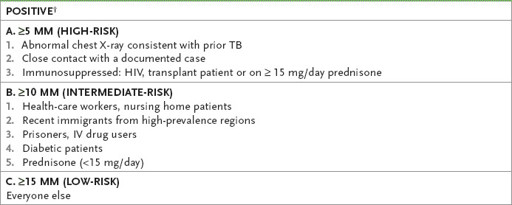

Selected serological tests may be helpful depending on the clinical setting (e.g. fungal, HIV, Q fever). An autoimmune screen – ANA, ESR, CRP, an EPG and complement levels – should be assessed if a connective tissue disease is suspected. However, remember that malignancy and infection can also cause an increase in acute phase reactants and a low-titre ANA. Check the purified protein derivative (PPD) for tuberculosis exposure (see

Table 13.2

).

Table 13.2

Tuberculin skin testing

*

If positive and no active disease on chest X-ray and by sputum for acid-fast bacteria: treat for latent TB (isoniazid for 9 months).

*

Contraindicated if history of necrotic skin reaction to previous testing. Prior BCG vaccination does not invalidate the results.

†

False negatives occur in anergy or with recent exposure (recheck after 12 weeks) or in the elderly (recheck after 3 weeks).

3.

If abdominal disease is suspected or other tests have not provided a clue, obtain a CT scan.

4.

Biopsy of involved tissue (e.g. bone marrow, liver, lymph node, skin, muscle) may lead to a definitive diagnosis. The clinical setting determines what should be biopsied.

5.

Exploratory laparotomy when all other tests are negative and in the absence of any evidence of abdominal disease is usually unproductive.

Treatment

Therapy directed at the underlying disease should be the goal of assessment. Therapeutic trials in the absence of a diagnosis (e.g. antibiotics, antituberculosis therapy, NSAIDs, steroids) may result in resistant bacterial infection or drug toxicity and may make accurate diagnosis difficult. If the patient is thought to have a fever caused by a drug – a

drug fever

– it may be worth stopping the drug or using an alternative one. A possible drug fever makes trialling a change of drug worthwhile.

HIV/AIDS

Patients with HIV infection or the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) have become increasingly available for long-case examinations. This is now often a chronic disease and patients are getting older and likely to have problems such as ischaemic heart disease. Remember that the diagnosis of AIDS can be made when someone infected with HIV has a CD4

+

cell count of <200 cells/μL or an HIV-associated disease. These patients present numerous diagnostic and management problems. The candidate will be expected to display a logical approach to the case and, of course, show a sympathetic attitude to the patient with this chronic disease. There needs to be a strong emphasis in the discussion on the psychological and social effects of the illness. Public health implications may also have to be addressed. Candidates should have an approach to pretest counselling for patients being tested for HIV.

The history

1.

Ask about the presenting symptoms. As usual for long cases, the candidate must find out what symptoms or complications are currently affecting the patient. These must be assessed in the context of possible longstanding disease affecting many systems of the body.

2.

Enquire when the virus was acquired. This is especially important in helping predict the likely level of immunosuppression. Not all patients are prepared to discuss this. Insistent questioning by candidates is not a good idea. There have been complaints from long case patients about this being handled insensitively.

a.

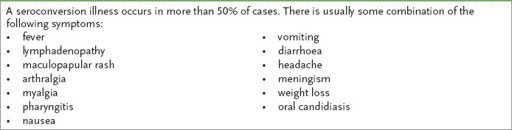

Find out about symptoms of a possible seroconversion illness in the past (see

Table 13.3

). Approximately 50% of people have a seroconversion illness. It occurs 3 to 6 weeks after infection and often resembles glandular fever. Remember that, without treatment, the development of AIDS takes roughly 7 to 10 years from the time of seroconversion. The occurrence of a seroconversion illness does not seem to be associated with a worse prognosis.

Table 13.3

Features of the seroconversion illness

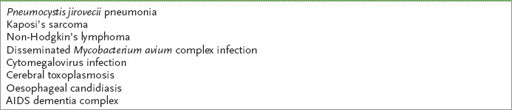

b.

Note from the history any of the conditions likely to occur during the period of mild-to-moderate immunosuppression that precedes the development of AIDS and those related to severe immunosuppression that define the development of AIDS (see

Table 13.4

).

Table 13.4

HIV-related conditions with severe immunosuppression

Note: This is a representative rather than an exhaustive list.

3.

Ask about the mode of acquisition of infection. Co-morbidity differs between subgroups, so specific questions about risk factors are essential. For example, co-infections with syphilis or papilloma viruses and Kaposi’s sarcoma is often found in the homosexual male subgroup, whereas hepatitis B and C infection, endocarditis, heroin nephropathy and other disorders related to drug abuse may complicate the disease in the intravenous drug-using group. Many haemophilia A patients acquired HIV from pooled blood products.

4.

Ask about sexual contacts. Contact tracing must be mentioned and the possibility of infection of sexual partners without their knowledge addressed. Ask the patient whether family and friends are aware of the diagnosis. Their attitude to this chronic illness may affect the patient’s ability to cope.