Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (79 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

HPO = hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy; SVC = superior vena cava.

1.

If necessary, ask the patient to undress to the waist and sit over the side of the bed.

2.

While standing back to make your usual inspection, ask whether sputum is available for you to look at. A large volume of purulent sputum is an important clue to bronchiectasis. Haemoptysis suggests lung carcinoma or pulmonary infection. Look for evidence of dyspnoea at rest and count the respiratory rate. Note the use of the accessory muscles of respiration and any intercostal indrawing of the lower ribs anteriorly (a sign of emphysema). General cachexia should also be noted.

3.

Pick up the patient’s hands. Note clubbing (see

Table 16.11

), peripheral cyanosis, nicotine (actually, tar) staining and anaemia, and look for wasting of the small muscles of the hands and weakness of finger abduction (which may be caused by a lower trunk brachial plexus lesion from apical lung carcinoma involvement). Palpate the wrists for tenderness but only if there is clubbing (hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPO), see

Fig 16.27b and c

). While holding the patient’s hand, palpate the radial pulse for tachycardia or obvious pulsus paradoxus.

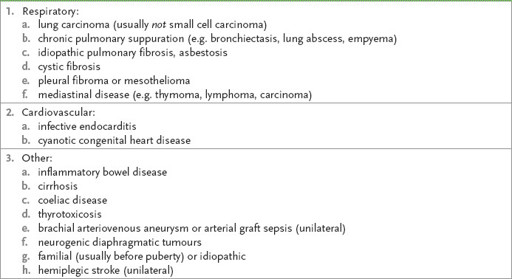

Table 16.11

Causes of clubbing

Note:

Clubbing does

not

occur with COPD, sarcoidosis, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis or silicosis. With this important sign decide whether it is definitely present or absent. Don’t call it ‘early’ if in doubt.

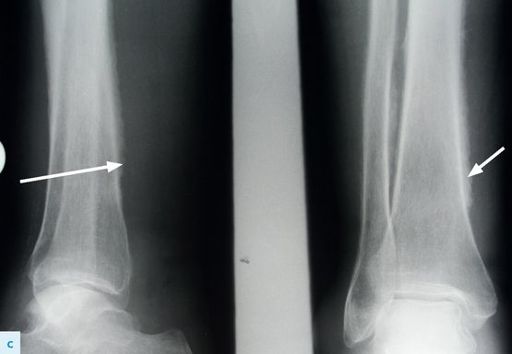

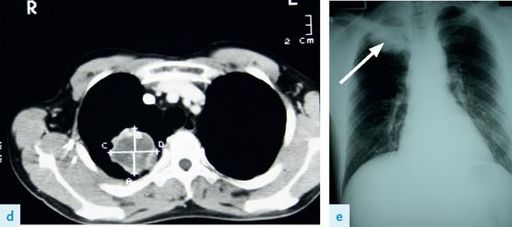

FIGURE 16.27

(a) Recurrent carcinoma of the lung following right upper lobectomy. Note mass and rib destruction.

(b) Hypertophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA) of the ulna in the same patient as in a. (arrow).

(c) HPOA of the tibia in the same patient as in (a) (arrows).

(d) CT scan of the chest showing a right upper lobe tumour – Pancoast tumour. (e) Chest X-ray of the same patient as in d showing right upper lobe tumour (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

4.

Go on to the face. Look closely at the eyes for ptosis and constriction of the pupils (Horner’s syndrome, p. 415). Inspect the tongue for central cyanosis.

5.

Palpate the position of the trachea.

6.

Note the presence of a tracheal tug, which indicates gross overexpansion of the chest with airflow obstruction. Ask the patient to cough and note whether this is a loose cough, a dry cough or, because of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, a bovine cough.

7.

Next measure the forced expiratory time (FET). Tell the patient to take a maximal inspiration and blow out as rapidly and completely as possible. Note audible wheeze. Prolongation of expiration beyond 3 seconds is evidence of chronic airflow limitation. If you wish to impress the examiners use a peak flow meter – normal 600 L/min for young men and 400 L/min for women. Doing these two tests can appear very impressive, but it must look smooth and practised.

HINT

Always ask the patient to cough.

8.

The next step is to examine the chest. You may wish to examine this anteriorly first or go around to the back. The advantage of the latter is that there are usually more signs there, unless the trachea is obviously displaced.

HINT

Deviation of the trachea is a most important sign, so spend time on it. If the trachea is displaced, concentrate on the upper lobes for physical signs. Upper lobe fibrosis causes tracheal deviation to the same side.

9.

Inspect the back. Look for kyphoscoliosis. Do not miss ankylosing spondylitis (p. 405), which causes decreased chest expansion and upper lobe fibrosis. Look for thoracotomy scars and prominent veins. Also note any skin changes from radiotherapy.

HINT

A large thoracotomy scar in a patient who looks Cushingoid suggests the possibility of a lung transplant. A unilateral transplant may leave signs on the other side, such as the crackles of ILD (pulmonary fibrosis), while the side with the scar sounds normal.

10.

Palpate the cervical nodes from behind. Then examine for expansion. First, upper lobe expansion is best seen by looking over the patient’s shoulders at clavicular movement during moderate respiration. The affected side will show a delay or decreased movement. Then examine lower lobe expansion by palpation. Note asymmetry and reduction of movement.

11.

Ask the patient to bring his elbows together in front of him to move the scapulae out of the way. Examine for vocal fremitus. Then percuss the back of the chest and include both axillae. Do not miss a pleural effusion (see

Table 16.12

).

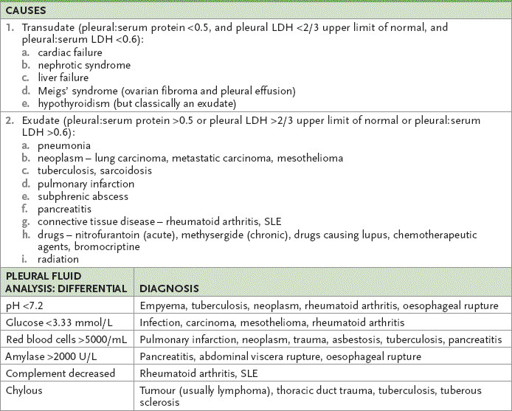

Table 16.12

Pleural effusion

LDH = lactate dehydrogenase.

12.

Auscultate the chest. Note breath sounds (whether bronchial or vesicular) and their intensity (normal or reduced) (see

Table 16.13

). Listen for adventitial sounds (crackles and wheezes) (see

Table 16.14

). Finally, examine for vocal resonance. If a localised abnormality is found, try to determine the abnormal lobe and segment.

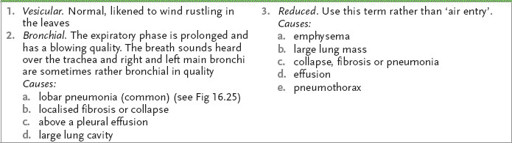

Table 16.13

Breath sounds

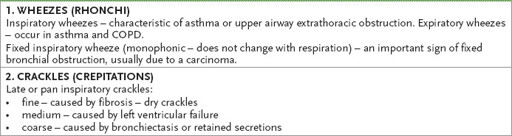

Table 16.14

Added sounds

Early inspiratory crackles: coarse – caused by COPD

13.

Return to the front of the chest. Inspect again for chest deformity, symmetry of chest wall movement, distended veins, radiotherapy changes and scars. Palpate the supraclavicular nodes carefully. Palpate the apex beat and measure chest expansion. Then test for vocal fremitus and proceed with percussion and auscultation as before. Listen high up in the axillae too. Before leaving the chest, feel the axillary nodes and breasts.

HINT