Exodus From Hunger (11 page)

Read Exodus From Hunger Online

Authors: David Beckmann

Tags: #Religion, #Christian Life, #Social Issues, #Christianity, #General

We can see similar patterns in modern history, in the fall of the Soviet Union for example. By the 1970s Communism no longer inspired many people in the Soviet Union. Even people in Moscow’s inner circles of power worked the system to their own benefit. Prophetic writers such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn did great damage to a tottering system by simply telling the truth. That powerful empire crumbled, mainly from within.

The United States’ continued vitality and world leadership depend on our ideals as much as anything else. If people around the world believe that the United States embodies and promotes moral principles, they are more likely to cooperate with us. Even more important, Americans themselves must continue to believe that our country stands for high principles. That conviction makes us and our nation’s leaders willing to sacrifice for the larger good. If we think we live in a dog-eat-dog society, we and our leaders are more likely to pursue our individual interests, even at the expense of the nation.

The United States is a wonderful country. Its moral strengths include tremendous freedom, creativity, diversity, and democracy. But our country typically gives higher priority to individual liberty, economic growth, and military strength than to helping poor people.

The Luxembourg Income Study, a comparison of poverty in twenty-one relatively high-income countries, sets its poverty line for each country at half of that country’s median income. By that measure, the United States has a higher rate of poverty than any other country except Mexico. Not coincidentally, government spending on social programs to reduce poverty is also lower in the United States than in all the other countries except Mexico.

3

U.S. official development assistance is tiny in relation to our national income—lower than nearly any of the other industrialized countries. If you broaden the analysis to include not just aid, but all the ways that industrialized countries affect developing countries (including trade, security policies, and so forth), the United States still ranks eighteenth among the industrialized countries.

4

Historically our nation’s tendency to neglect poor people has often been justified as a corollary of our love of liberty. For example, Ralph Waldo Emerson argued for “self-reliance” and against charity as a matter of principle:

Do not tell me, as a good man did today, of my obligation to all poor men in good situations. Are they my poor? I tell thee thou foolish philanthropist that I grudge the dollar, the dime, the cent, I give to such men as do not belong to me and to whom I do not belong.

5

In

Democracy in America

(1835), Alexis de Tocqueville invented the word “individualism” to describe a cultural trait he noted among Americans. It was rooted in the exceptional drive of people in this young nation toward economic advancement. Tocqueville worried that Americans’ excessive preoccupation with their personal affairs could weaken U.S. democracy.

Another well-worn argument against greater efforts to reduce poverty is that free markets will do the job more effectively. Herbert Hoover devoted the final speech of his 1928 presidential campaign to a defense of America’s “rugged individualism” as opposed to the “socialism and paternalism” of Europe:

By adherence to the principles of decentralized self-government, ordered liberty, equal opportunity, and freedom to the individual, our American experiment in human welfare has yielded a degree of well-being unparalleled in the world. It has come nearer to the abolition of poverty, the abolition of fear of want, than humanity has ever reached before.

6

Hoover’s argument won that election, but it didn’t ring true any more once the Great Depression hit. Increasing hunger and poverty throughout the early years of the twenty-first century has driven home the point again: freemarket policies and economic growth do not automatically open opportunity for everybody.

In the United States we enjoy extraordinary security. Our country hasn’t been invaded by foreign troops for two hundred years, and we can also count on economic and political systems that are stable and work fairly well. In many countries, people suffer huge disruptions in their lives due to massive economic malfunction or disorderly, sometimes violent struggles for power.

But our exceptional security is now somewhat threatened—by serious economic problems, strained relations with the rest of the world, and deep internal divisions. The U.S. public is anxious and is looking to political leaders for solutions.

Our national discussion of these problems focuses on obvious solutions. To improve the economy, we will need to get macroeconomic management right. To improve international relations, we hope to bring the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to successful conclusions. To deal with our internal divisions, we look for changed behavior from political leaders and interest groups. But with a cue from the biblical teaching that justice for poor people is important to national security, we can see that an expanded effort to reduce poverty would also help to address each of these big problems that currently threaten U.S. security.

First, the economy will be stronger and more secure for all of us if poor people can participate fully in economic recovery. An economic recovery that leaves much of the U.S. population and many developing countries in financial crisis cannot be robust. When unemployed people get jobs, they contribute to economic production and have income to spend. When dynamic developing economies recover high rates of growth, their increased imports and innovations are tonic for the entire global economy.

Over the long term, improvements in the nutrition, health, and education of poor people generate high returns for everybody. Microsoft founder Bill Gates put it this way:

Inequity is the most harmful force in the world—not just because it leaves people in misery, but because it wastes human potential and undercuts society’s best chance to solve its own problems. As you begin to solve inequity, you decrease the number of problems, and increase the number of problem-solvers. That’s why I believe some of the highest-leverage, long-term investments come from improving public education, especially for low-income and minority students, and increasing development assistance for the poorest countries.

7

President Obama and a Democratic Congress rightly included investments in poor people in their stimulus program in early 2009, and further antipoverty measures would also be good for the economy as a whole. Bringing deficit spending down is important, too, but that will require attention to the big-ticket elements in the federal budget (taxes, military spending, Social Security, and Medicare). The spending required to boost progress against hunger and poverty is tiny in relation to our $3.5 trillion federal budget.

The link between global poverty and improved U.S. relations with the rest of the world—another big challenge to our national security—is also clear. Poor people throughout the world are struggling for a better life. If the world’s superpower is perceived to stand in the way of that better life, we invite resentment and opposition from developing countries. But if the United States deploys its power generously, many people around the world—in the other industrialized countries, too—will cooperate with our country and the international systems in which we have influence.

The United States is especially concerned about its relations with the Muslim world, and more than a third of the people living in absolute poverty in the world are Muslim.

8

Not too long ago I visited two Muslim countries, Turkey and Egypt. Turkey’s western cities now remind me of Italy or Spain, and Turkey is eager to join the European Union. Egypt, on the other hand, is poor and threatened by violent strains of Muslim extremism. After visiting these two countries, it is hard to miss the relevance of economic development to U.S. international relations.

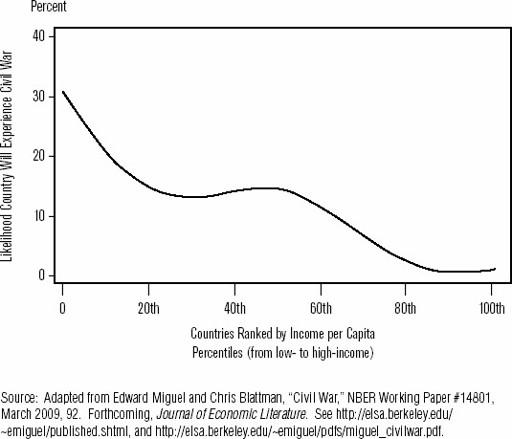

Poverty breeds violence. As countries escape from poverty, civil war becomes less likely (see

Figure 6

).

The problems of poor countries pose other threats to security, too. Susan Rice, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, explains:

These threats could take various forms: a mutated avian flu virus that jumps from poultry to humans in Cambodia or Burkina Faso; a U.S. expatriate who unwittingly contracts Marburg virus in Angola and returns to Houston on an oil company charter flight; a terrorist cell that attacks a U.S. Navy vessel in Yemen or Somalia; the theft of biological or nuclear materials from poorly secured facilities in the former Soviet Union; narcotics traffickers in Tajikistan and criminal syndicates from Nigeria; or, over the longer term, flooding and other effects of global warming exacerbated by extensive deforestation in the Amazon and Congo River Basins.

9

Figure 6

Incidence of Civil War by Country Income, 1960-2006

President Obama’s election gave the United States a fresh start in its international relations, and leaders from both parties have supported increases in international development assistance. But little progress has been made toward moderation of the deep and bitter divisions

within

U.S. society and politics—and that may be the most serious threat to U.S. security.

Whether in Washington, DC, or at the local level, liberals and conservatives are still inclined to demonize people on the other side. With Democrats and Republicans unable to work well together, we may be in for several years of political gridlock. A house divided against itself cannot solve its other problems.

Our political divisions grow partly out of class divisions. Over the last twenty-five years the share of income received by the richest 1 percent of the U.S. population has doubled, while median family income has been stagnant, and the real wages of low-income workers have fallen. When Americans are asked if their country is divided between the haves and have-nots, half say yes—up from one-fourth thirty years ago.

10

Affluent people and their organizations finance candidates, think tanks, lobbyists, and media companies to work for policies that serve their interests. When I visit the Capitol office buildings, the representatives of many special interests are there in force. Special interests make it hard for Congress to tackle many problems, and the influence of money in politics skews the system against changes that would help people who don’t have much money. The Supreme Court decision in the case of

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

to let corporations contribute directly to political campaigns will make this problem worse.

Understandably, many middle- and low-income people are frustrated with government. They know that government doesn’t work very well for them. Some are liberal, and some are conservative; many have become cynical. The great majority of voters have come to agree on one thing: we need change. That’s why both candidates in the last presidential election—Barack Obama and John McCain—campaigned as candidates for change.

The only path forward may be for Congress to achieve some real change for the better. If the 2010 reform of health care really improves health care for middle- and low-income people, for example, that will encourage people to work together on other national problems. A more active, positive-minded citizenry will make it tougher for special interests to stand in the way.

If we can achieve changes that reduce hunger and poverty, that would be especially inspiring. We could dramatically reduce hunger among American children, for example. This could be a bipartisan initiative, and it would engage states and community groups in collaboration with federal programs. After three or four years, churches could be telling their members that it’s no longer so urgent that they bring groceries to church—that concerned people can turn their attention to tutoring programs and other ways of helping. When that day comes, a lot of Americans—rich, poor, and in between—will feel good about our country and ready to work together on other problems.

If we can get the United States to make a more serious effort to reduce hunger and poverty, our economy will be more dynamic, our relations with the rest of the world improved, and our society more united. Our country will be better—and more secure.

PEOPLE OF FAITH CAN MAKE CONGRESS WORK

When asked if I am pessimistic or optimistic about the future, my answer is always the same: If you look at the science about what is happening on earth and aren’t pessimistic, you don’t understand data. But if you meet the people who are working to restore this earth and the lives of the poor, and you aren’t optimistic, you haven’t got a pulse. What I see everywhere in the world are ordinary people willing to confront despair, power, and incalculable odds to restore some semblance of grace, justice, and beauty to this world

.Paul Hawken

1