Exodus From Hunger (5 page)

Read Exodus From Hunger Online

Authors: David Beckmann

Tags: #Religion, #Christian Life, #Social Issues, #Christianity, #General

The global economy now connects everything to everything, and today’s multifaceted economic malfunction is likely to trigger more problems we can’t anticipate. But I am optimistic about economic recovery, mainly because the peoples and nations of the world have a record of resilience in tough economic times.

I am also encouraged by the way the United States and other governments have responded to the crisis. President George W. Bush’s bank-recovery program in 2008 kept the financial crisis from spinning out of control, and President Barack Obama followed with a massive stimulus bill in 2009.

Half of the $850 billion in President Obama’s stimulus bill went to programs that include low-income people. When Bread for the World’s analysts first reported this, I asked them to check their figures. The news seemed too good to be true. But focusing on low-income people made sense, because they most needed help. Also, low-income people spend nearly all the money they get, so help for low-income people quickly boosts the rest of the economy.

President Obama was also right to use some of the stimulus funding for initiatives to make the U.S. economy more environmentally sustainable—programs to weatherize schools and low-income housing, for example. Climate change is real, and a recovery that ignores environmental constraints will not be long-lasting.

The United States won’t recover to the society we were before this economic crisis. We will recover to something different, and we can use this crisis to decide what kind of nation we want to be. Many families have reacted to financial constraints by deemphasizing consumption and putting more emphasis on the things money can’t buy. At the same time, about half of U.S. voters say the economic crisis has made them more supportive of policies and programs to help hungry and poor people.

18

We just might achieve lasting cultural changes for the better, just as the generation that endured the Great Depression learned lifelong lessons about hard work, frugality, compassion, and the value of government social programs.

DRAMATIC PROGRESS IS FEASIBLE

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference

.—Reinhold Niebuhr

M

ost people think world hunger is absolutely hopeless, something we cannot change. Trying to end world hunger seems quixotic, almost a joke. But dramatic progress against hunger and poverty is possible.

I don’t think we can do away with

all

hunger. Some addicts, for example, will be so consumed with their addiction that they will fail to secure food for themselves. Globally there will continue to be outbreaks of hunger in countries that are oppressed by war or tyrants.

But we do not have to accept the intermittent hunger of 49 million people who live in food-insecure families in the United States. Once the economy is growing again, it is feasible to drive down the extent of hunger in America to, say, 5 million people. Developing countries that are at peace and have decent governments can also dramatically reduce hunger. Some developing countries have reduced both hunger and poverty, and it’s easier to reduce hunger than poverty, because food assistance programs can end hunger among families that are still poor. Within several decades, we can reduce the number of undernourished people in the world from 1 billion people to, say, 100 million, ending the routine mass hunger that has plagued humanity throughout history.

In the 1990s Bread for the World Institute tried to figure out what it would take to end hunger. Many people and institutions around the world were thinking along the same lines.

A series of U.N. conferences in the 1990s set global goals for the environment, hunger, population, and other issues. By the end of the decade, the development assistance agencies of industrialized countries wanted to boil these agreements down into a manageable set of goals, with quantitative indicators by which they could monitor progress. These goals were embraced by the heads of government of the eight most powerful countries in the world at their annual Group of 8 (G8) Summit.

At the United Nations, the developing countries also embraced these goals. They added some specifics about what the industrialized countries should do to help, and virtually all the nations of the world approved them in 2000 as the Millennium Development Goals.

1

Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama have both affirmed that the United States will do its part to achieve these historic goals.

THE MILLENNIUM

DEVELOPMENT GOALS

Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Achieve universal primary education

Promote gender equality and empower women

Reduce child mortality

Improve maternal health

Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

Ensure environmental sustainability

Develop a global partnership for development

The Millennium Goals articulate aspirations that people around the world now share. Virtually all the world’s religions and competing ideologies affirm efforts to overcome hunger, extreme poverty, and related ills. Many governments and people around the world are now using the Millennium Goals to guide and measure their work. Bread for the World focuses on hunger, but we understand that hunger is interconnected with the other aspects of poverty, so we have embraced the Millennium Goals as the framework for our international advocacy.

When the Millennium Development Goals are described to Americans, about half of us find them inspiring. The other half find the idea of a comprehensive, internationally agreed strategy to reduce poverty utopian. But if you ask about specific goals—letting all the world’s children go to school, for example—nearly all Americans are supportive.

2

The Millennium Goals helped inspire the industrialized countries to more than double the amount of their total development assistance from $53 billion in 2000 to $121 billion in 2008.

3

The donor countries have also agreed, at least in theory, on strategies to improve the quality of development assistance.

4

Many developing-country governments are using the goals to track development progress, and some have focused additional resources on achieving the goals.

The United Nations has done a good job promoting the Millennium Goals and monitoring how the world is doing in relation to the quantitative targets. I served on the Hunger Task Force for the U.N. Millennium Development Goals Project, led by Jeffrey Sachs, one of the world’s leading economists. The project developed strategies for achieving the goals, including estimates of what it would cost and how much of the cost could be borne by poor countries themselves. Sachs concluded in 2005 that annual development assistance from the industrialized countries would need to increase by roughly $70 billion right away, with the increase rising to $130 billion by 2015.

5

If the United States would provide a fourth of $130 billion (which is sometimes considered our fair share for joint projects among the industrialized countries), the U.S. share of the cost would be roughly $33 billion.

More development assistance will not, by itself, cut world poverty in half and achieve the other Millennium Goals. Hundreds of millions of poor people must—and will—work hard over many years. Corrupt governments need to be reformed or replaced. The quality of development assistance and trade policies needs to improve. But the $33 billion figure gives us a rough idea of how much it would cost the United States to do its share to achieve the Millennium Development Goals.

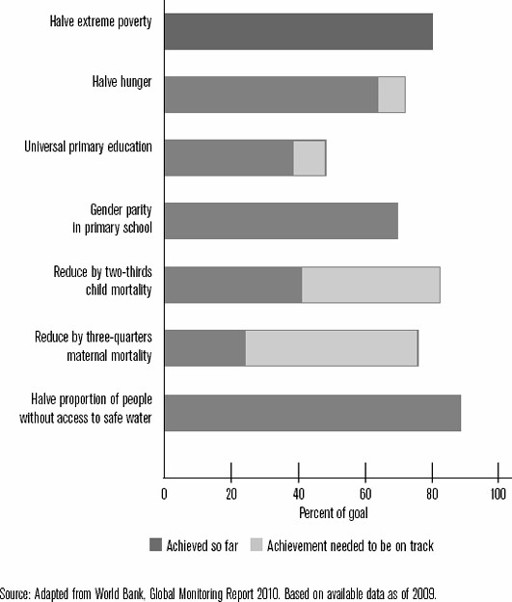

Most developing countries are not on track to meet all the goals. Progress has lagged far behind targets in some of the poorest countries and for some of the goals—notably, maternal health and sanitation. Yet the accomplishments for the developing countries as a whole are striking:

— The proportion of children under five years old who are underweight declined by one-fifth between 1990 and 2005.

— Enrollment in primary school increased from 80 percent in 1991 to 88 percent in 2006. Much of this increase is because girls are now going to school, too.

— The number of deaths from AIDS fell from 2.2 million in 2005 to 2 million in 2007, and the number of people newly infected declined from 3 million in 2001 to 2.7 million in 2007.

— Deaths from measles dropped by two-thirds between 2000 and 2006. The incidence of tuberculosis has stabilized or begun to fall in most regions. Malaria prevention is expanding rapidly.

— 1.6 billion people have gained access to safe drinking water since 2001.

6

The gap between rich and poor in the world is extreme: the richest 10 percent of the world’s people receive roughly one-half of total world income, while the poorest 10 percent receive less than 1 percent. It is not clear whether the global distribution of income is becoming more or less unequal.

7

But if the pace of progress against extreme poverty that was maintained between 1990 and 2005 can be achieved for the decade between 2005 and 2015, the world will cut extreme poverty in half between 1990 and 2015.

That last sentence bears repeating: If the pace of progress against extreme poverty that was maintained between 1990 and 2005 can be achieved for the decade between 2005 and 2015, the world will cut extreme poverty in half between 1990 and 2015.

Figure 5

Progress toward the Millennium Development Goals

Source: Adapted from World Bank, Global Monitoring Report 2010. Based on available data as of 2009

In the 1990s the two most discouraging themes in international development were Africa and AIDS. Nearly all African countries had suffered decades of economic decline, and AIDS was completely out of control, killing off much of a generation in some countries.

But much of Africa has since then made huge changes for the better. Most notably, 29 million more African children are in school today than in the year 2000.

Steve Radelet, development advisor to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, is finishing a book on Africa which is titled, aptly,

Emerging Africa: The Unheralded Development Turnaround in (Half of) Africa

. Steve notes that seventeen countries in sub-Saharan Africa have since 1995 increased the average income of their people by 50 percent and reduced poverty by 20 percent. All but three of these countries have also become democracies.

8

The world has also fought back against AIDS. Few HIV and AIDS patients in developing countries had access to AIDS medication in the 1990s. Now 3 million patients are on antiretroviral medication.

9

Nearly all of them are living normal, productive lives. The availability of medication has also encouraged people to seek testing for HIV, thus helping to reduce the disease’s spread.

Many developing countries have also managed to put dictatorship and war behind them. The number of developing countries holding elections increased from 91 in 1991 to 121 in 2008.

10

The end of the Cold War and increased peacemaking efforts by the United Nations have reduced the number of wars in developing countries over the past thirty years.

11

Radios and cell phones are now widespread in poor countries. Two hundred million Africans have cell phones, and that number is growing by 60 million a year. Isolated farm families use them to learn about farm prices at market and to contact family members working in the city, and improved communication is also helping to make governments more accountable.

I once asked a former minister of agriculture in Uganda why her government had been responsive to the people even before the formal transition to democracy. She noted that Uganda now has fifty radio stations that broadcast music and news in many languages. When she was interviewed on radio, farmers would call from remote parts of Uganda to let her know if her programs weren’t working well in their areas.

The 2010 earthquake in Haiti again brought images of extreme suffering into our living rooms. Haiti faces exceptional challenges—a long history of exploitation by foreign powers, class conflicts, corruption, and now a massive reconstruction task. Yet the number of deaths due to routine poverty around the world is equivalent to a Haitian earthquake every week, and the ongoing poverty of Bangladesh or Tanzania seldom shows up on our television screens. All the good news that is coming from countries like Bangladesh and Tanzania almost never shows up on our television screens.