Exorcising Hitler

Authors: Frederick Taylor

EXORCISING

HITLER

The Occupation and

Denazification of Germany

FREDERICK TAYLOR

To Götz Bergander, Joachim Trenkner and Helmut Schnatz, who were born to a regime founded in war and intolerance but, along with so many others, helped to build something much, much better in its place.

All the time I am asking myself why this misfortune came over me. How have I deserved this? What have I done that one has to treat me like a criminal? That so many people died in Belsen – I could not alter that any more. It is all my fate and maybe I shall even be punished for that.

– Josef Kramer, commandant of Belsen concentration camp, in a letter to his wife before his execution

Lily the Werwolf is my name.

Hoo, Hoo, Hoo,

I bite, I eat, I am not tame.

Hoo, Hoo, Hoo.

My Werwolf teeth bite the enemy,

And then he’s done and then he’s gone,

Hoo, Hoo, Hoo.

– the song ‘Werwolf Lily’, broadcast to ‘German youth’ by the radio station of the Nazi

Werwolf

resistance, spring 1945

Your attitude toward women is wrong – in Germany. You’ll see a lot of good-looking babes on the make there. German women have been trained to seduce you. Is it worth a knife in the back?

– booklet for the guidance of GIs in Germany, late 1944

German people, you must know that if the war is lost, you will be annihilated! The Jew with his infinite hatred stands behind this concept of annihilation. And if the German people loses here, then its next ruler will be the Jew! And what a Jew is, this must be known to you. And if anyone doesn’t know about the revenge of Juda, let him read about it. This war is not the Second World War, this war is the great racial war.

– Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, Harvest Thanksgiving Speech,

Berlin Sportpalast, 4 October 1942

God, I hate the Germans.

– General Dwight D. Eisenhower in a letter to his wife Mamie, September 1944

Contents

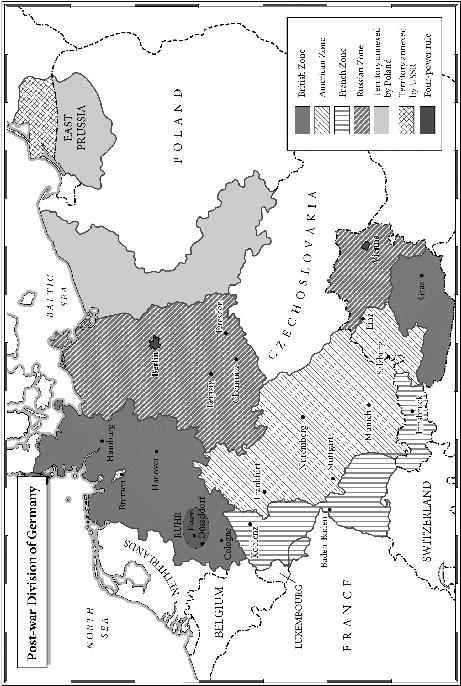

In the spring of 1945, the four major powers that had defeated Hitler’s armies took an unprecedentedly drastic step: they abolished Germany’s sovereign government and took direct control of its territory. A few months later, Allied Military Administration was also imposed on Germany’s main co-combatant in the Second World War, the Japanese empire. With these acts, the victorious Allies undertook what most people at the time thought of as an exceptional and final exercise in foreign military occupation of hitherto independent peoples. From now on, with the world cleansed of aggressive war, such measures would no longer be necessary.

Partly due to pressure from America and Russia, the two ‘post-colonial’ superpowers created by the Second World War, the British, French and Dutch empires soon began to dissolve. India, Burma and Indonesia quickly gained their independence, to be followed, as the 1950s and 1960s progressed, by huge areas of Asia and Africa. The model for the post-war world would, so the largely American-sponsored orthodoxy had it, be one of national sovereignty and self-government. Aggressive wars of choice, campaigns of gratuitous conquest, would no longer be tolerated, and those on the enemy side who had conducted, in the view of the Allies, such a war between 1939 and 1945 would be punished. Hence the Nuremberg and Tokyo war crimes trials that followed the surrenders of Germany and Japan.

There was, of course, a key difference between the occupations of Germany and Japan after 1945. Although in the case of both countries the Allies had demanded unconditional surrender, the Japanese were in the final analysis – for pragmatic reasons –permitted a condition, which was that they could keep their emperor. Only in the case of Germany was all government, from the highest national level to the most parochial, taken, at the moment of surrender, completely into the victors’ hands, and the German people thereby entirely delivered up to the mercy of their erstwhile enemies.

Who, more than sixty years ago, would have ever thought that, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, two of those Western powers would be again conducting military occupations of formerly sovereign states? And who would have predicted that those new occupations, after the crucial learning experiences of 1945, would be so halting, so clumsy, so violently problematic?

The invasion of Iraq by America and its coalition allies brought the swift demise of Saddam Hussein’s pseudo-fascist Ba’athist state, and the country’s occupation by foreign forces. In many respects, the victorious coalition’s strategy, such as it was, seemed to resemble that employed by the Western Allies for their occupation of Germany in the wake of Nazism – that is, immediate demilitarisation of the defeated, along with temporary abolition of sovereign government, pending elimination of security threats and political cleansing, in this case ‘De-Ba’athification’. Then, finally, punishment of those guilty of political crimes, to be followed by step-by-step introduction of Western-style free institutions and representative government.

It is no spoiler to state here and now that after 1945 this recipe for the reconstruction and rehabilitation of the defeated nations was, with hindsight and in the longer term, a success. All we need to do is look at twenty-first-century Germany. There were reasons for this, some obvious and some not. First, to stick to Germany, it was true that the country in May 1945 was absolutely defeated. In November 1918, by contrast, though exhausted and starved and already in the throes of internal revolution, Germany had still been fighting stubbornly on French and Belgian soil when she conceded the truce that eventually brought the First World War to an end.

The German state survived this peace, although authoritarian monarchical rule was abolished. The Reich’s government and constitution became democratic, but the official and military classes remained both influential and fervently nationalist, eager to evade the provisions of the harsh Versailles Treaty and secretly longing to avenge what they saw as an unjust defeat – one that they blamed, in great measure, on the revolutionaries who had overthrown the Kaiser.