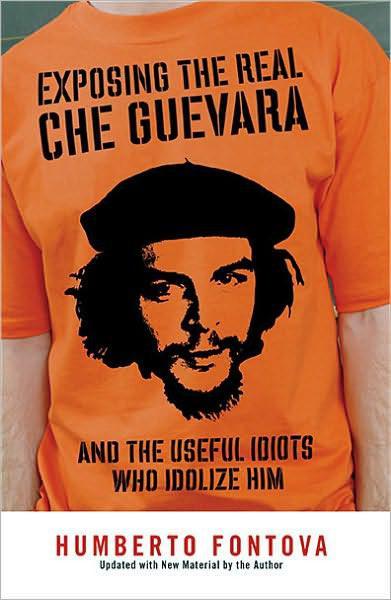

Exposing the Real Che Guevara

Read Exposing the Real Che Guevara Online

Authors: Humberto Fontova

Tags: #Political Science / Political Ideologies

Table of Contents

SENTINEL

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Mairangi Bay, Auckland 1311,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2007 by Sentinel, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Mairangi Bay, Auckland 1311,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2007 by Sentinel, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © Humberto Fontova, 2007

All rights reserved

Insert credits: Joaquin Sanjenis, courtesy of Ricardo Nũnez-Protuondo: p. 1; AP/Wide World Photos / Jose Goita:

p. 2 top; AP/Wide World Photos / Amy Sancetta: p. 2 bottom; AP/Wide World Photos / Dario Lopez-Mills: p. 3

top; AP/Wide World Photos / Chris Pizello: p. 3 bottom;

startraksphoto.com

/ Bill Davila: p. 4 top; AP/Wide

World Photos / Keystone / Laurent Gilleron: p. 4 bottom; AP/Wide World Photos / Joe Cavaretta: p. 5; Emilio

Izquierdo Jr. / photographer unknown: p. 6 top; Emilio Izquierdo Jr. / photographer unknown: p. 6 bottom;

Barbara Rangel / photographer unknown: p. 7; Felix Rodriguez / photographer unknown: p. 8.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Fontova, Humberto.

Exposing the real Che Guevara : the liberal media’s favorite executioner / Humberto Fontova.

p. cm.

Insert credits: Joaquin Sanjenis, courtesy of Ricardo Nũnez-Protuondo: p. 1; AP/Wide World Photos / Jose Goita:

p. 2 top; AP/Wide World Photos / Amy Sancetta: p. 2 bottom; AP/Wide World Photos / Dario Lopez-Mills: p. 3

top; AP/Wide World Photos / Chris Pizello: p. 3 bottom;

startraksphoto.com

/ Bill Davila: p. 4 top; AP/Wide

World Photos / Keystone / Laurent Gilleron: p. 4 bottom; AP/Wide World Photos / Joe Cavaretta: p. 5; Emilio

Izquierdo Jr. / photographer unknown: p. 6 top; Emilio Izquierdo Jr. / photographer unknown: p. 6 bottom;

Barbara Rangel / photographer unknown: p. 7; Felix Rodriguez / photographer unknown: p. 8.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Fontova, Humberto.

Exposing the real Che Guevara : the liberal media’s favorite executioner / Humberto Fontova.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-595-23027-0

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

PREFACE

“These CubanS Seem to not have slept a wink since they grabbed their assets and headed for Florida,” Michael Moore writes in his book

Downsize This!

Downsize This!

Some Cubans certainly “grabbed assets,” but not those who headed for Florida. Michael Moore might have profited from witnessing the scenes at Havana’s Rancho Boyeros airport in 1961 as tens of thousands of Cubans “headed for Florida” and “assets were grabbed.”

My eight-year-old sister Patricia, my five-year-old brother, Ricky, and this writer, then seven years old, watched as a scowling

miliciana

jerked my mother’s earrings from her ears. “These belong to

La Revolución

!” the woman snapped, and then turned toward my sister. “That, too!” and she reached for the little crucifix around Patricia’s neck, pulling it roughly over her head. My mother, Esther, winced and glowered, but she’d been lining up the paperwork for our flight to freedom for a year. She wasn’t about to botch it now.

miliciana

jerked my mother’s earrings from her ears. “These belong to

La Revolución

!” the woman snapped, and then turned toward my sister. “That, too!” and she reached for the little crucifix around Patricia’s neck, pulling it roughly over her head. My mother, Esther, winced and glowered, but she’d been lining up the paperwork for our flight to freedom for a year. She wasn’t about to botch it now.

For millions of Cubans, being able to leave your homeland utterly penniless and with the clothes on your back for an uncertain future in a foreign country was (and is today) considered the equivalent of winning the lottery. My mother, a college professor, bore the minor larceny stoically. My father, standing beside her, had just emptied his pockets for another guard as his face hardened. Humberto Senior was an architect. That look (we knew so well) of an imminent eruption was manifesting. Suddenly, uniformed men surrounded Humberto. “

Señor,

you’re coming with us.”

Señor,

you’re coming with us.”

“To where?” my mother gasped.

“You! Keep your mouth shut!” snapped the

miliciana

. And Humberto was dragged off. “Then we’re not leaving!” said my mother as she tried to follow him. “If you can’t leave, we’re not leaving!” She started to choke up.

miliciana

. And Humberto was dragged off. “Then we’re not leaving!” said my mother as she tried to follow him. “If you can’t leave, we’re not leaving!” She started to choke up.

My father stopped and turned around as the men grabbed his arms. “You

are

leaving,” he said. “Whatever happens to me—I don’t want you and the children growing up in a communist country!” It would be a few weeks before Castro admitted he was a Marxist-Leninist. At the word “communist,” my father’s police escort bristled and jerked him forward.

are

leaving,” he said. “Whatever happens to me—I don’t want you and the children growing up in a communist country!” It would be a few weeks before Castro admitted he was a Marxist-Leninist. At the word “communist,” my father’s police escort bristled and jerked him forward.

“We’re not leaving!” yelled my mother.

“You are!” yelled my father over his shoulder as he disappeared through the doors. As the doors snapped shut my mom finally broke down. Her shoulders heaved and her hands rose to wipe the tears, but her arms were promptly pulled down by the white-knuckled clutches of her terrified children’s little hands. So again my mom composed herself.

“Papi will be out in a minute,” she smiled at us while wiping the tears. “He forgot to sign some papers.”

Two hours later everyone was lining to board the flight for Miami. But Papi had not emerged from those doors. The agonized look returned to mother’s face. It was time for a decision. Cuba’s prisons were filled to suffocation at the time. Firing squads were working triple shifts. But her husband had made himself very clear.

“Let’s go!” she stood and blurted. “Come on, kids. Time to go on our trip! Papi will meet us later . . .” she gasped and her shoulders started heaving again. Her children’s white-knuckled clutches returned to her hands, and we joined that heartsick procession to the big plane, a Lockheed Constellation.

Seeing the big plane, climbing aboard, and hearing the engines crank up excited me, and for a few minutes I forgot about my dad.

“

Volveremos!

” yelled a man a few seats in front of us. Others picked up the cry. Doug MacArthur’s famous “I shall return” had been picked up by Cubans, but in the plural. South Florida was alive with exile paramilitary groups, and no one expected that during the height of the Cold War the United States would acquiesce in a Soviet client state ninety miles from its border. The man who started the chant fully expected to be back soon, carbine in hand.

Volveremos!

” yelled a man a few seats in front of us. Others picked up the cry. Doug MacArthur’s famous “I shall return” had been picked up by Cubans, but in the plural. South Florida was alive with exile paramilitary groups, and no one expected that during the height of the Cold War the United States would acquiesce in a Soviet client state ninety miles from its border. The man who started the chant fully expected to be back soon, carbine in hand.

But it was mostly women and children who filled that huge plane, and soon their gasps, sniffles, and sobs were competing with the shouts and the engine noise.

We landed in Miami and somehow found our way to a cousin’s little apartment. These relatives had left a few months earlier. From their crowded little kitchen Mom quickly dialed the operator for a call to our grandmother, still in Cuba. The connection went through and she immediately asked about my father. There was a light pause. She frowned, and then she dropped the receiver and fell to the floor.

Her frightened children got to her first. “

Qué pasa!

” Patricia wailed. Our mother was not moving. While one aunt took her in her arms, another picked up the phone, raised it to hear, and somehow made herself heard over the din in that kitchen. Aunt Nena was nodding with the phone pressed to her ear. “Ayy no!” she finally shrieked.

Qué pasa!

” Patricia wailed. Our mother was not moving. While one aunt took her in her arms, another picked up the phone, raised it to hear, and somehow made herself heard over the din in that kitchen. Aunt Nena was nodding with the phone pressed to her ear. “Ayy no!” she finally shrieked.

My mother had fainted. Aunt Nena came close when she heard the same thing over the phone. Our father was a prisoner at El G-2 in Havana. This was the headquarters for the military police. Prisoners went to El G-2 for “questioning.” From there most went to the La Cabana prison-fortress for “revolutionary justice.” But many did not survive the “questioning.” The Cuba Archive Project has documented hundreds of deaths at G-2 stations. This was a process that the Left is willing to call by its proper name—“death squads”—anywhere else in Latin America but Cuba.

In a few moments, my mother regained consciousness, but I cannot say she revived. Penniless and friendless in a strange new country, with three children to somehow feed, clothe, school, and raise, Esther Maria Fontova y Pelaez believed herself to be a widow.

A few months later, we were in New Orleans, where we also had relatives, with a little more room in their apartment (only three Cuban refugee families were holed up inside). From this little kitchen my mother answered the phone one morning. Her shriek brought Patricia, Ricky, and me rushing into the kitchen. But this was a shriek of joy. It was Papi on the line—and he was calling from Miami! He had gotten out.

Mom’s shriek that morning still rings in our ears. Her scream the following day as Dad emerged from the plane’s door at New Orleans’ international airport was equally loud. The images of Mom racing across the tarmac, Papi breaking into a run as he hit the ground, and our parents embracing upon contact will never vanish, or even dim.

Today my father hunts and fishes with his children and grand-children every weekend. Our story had a happy ending. But thousands upon thousands of Cuban families were not as fortunate. One of them was my cousin Pedro’s.

That same year, 1961, Pedro was a frail, mild-mannered youth who taught catechism classes at his church in the La Vibora section of Havana. He always came home for lunch and for dinner. One night he didn’t show up, and his mother became worried. After several phone calls she became frantic. People were disappearing all over Cuba in those days. She called the local priest, and he promptly joined the search. Father Velazquez was a longtime friend of Pedro, who taught religion classes in his very parish, and quickly suspected something serious. This wasn’t like Pedro.

The priest called the local first-aid station and tensed when told that, yes, in fact, the body of a slim, tall youth fitting Pedro’s description had been brought in. Father Velazquez hurried down to the station and had his worst fears confirmed. He quickly called my aunt with the news.

Other books

AllTangledUp by Crystal Jordan

Tishomingo Blues by Elmore Leonard

The Reunion by Everette Morgan

Final Cut by Lin Anderson

Unlucky in Love by Maggie McGinnis

Sunset Limited by James Lee Burke

I See Me by Meghan Ciana Doidge

Parsifal's Page by Gerald Morris

Wild Thunder by Cassie Edwards

Highbridge by Phil Redmond