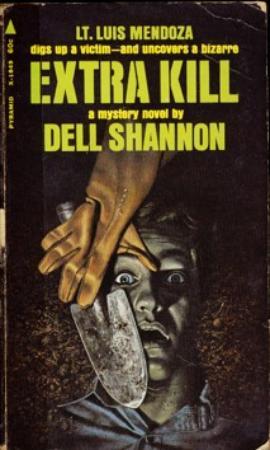

Extra Kill - Dell Shannon

Read Extra Kill - Dell Shannon Online

Authors: Dell Shannon

Extra Kill

Dell Shannon

1961

Jaques:

And then he

drew a dial from his poke,

And, looking on it

with lack-lustre eye,

Says very wisely, "It

is ten o'clock.

Thus may we see," quoth

he, "how the world wags.

'

Tis but an

hour ago since it was nine;

And after one

hour more 'twill be eleven;

And so, from hour

to hour, we ripe and ripe,

And then, from

hour to hour, we rot and rot;

And thereby

hangs a tale."

—

As You Like It, Act

II, sc. 7

ONE

That he was making history was an idea that didn't

enter the head of the rookie cop Frank Walsh. He was riding a squad

car alone for the first time, which made him more conscientious than

usual. He saw this car first when they pulled up at a stop light

alongside each other on Avalon Boulevard; he'd never seen one like it

and was still looking for some identification when the light changed

and it took off like a rocket. He was going the same way, and it was

still in sight when they passed a twenty-five-mile zone sign; it

didn't slow down, and Walsh happily opened up and started after it.

The bad old days of quotas for tickets, all that kind

of thing, were long gone—and Frank Walsh was twenty-six, no

starry-eyed adolescent; nevertheless, there was a kind of

gratification, a kind of glamour, about the first piece of business

one got alone on the job. In time to come, he would have kept an eye

on that car for a while, clocked it as only a little over the legit

allowance and obviously being handled by a competent driver, and let

it go. As it was, a mile down Avalon he pulled alongside and motioned

it into the curb.

It was quite some car, he thought as he got out and

walked round the squad car: a long, low, gun-metal-colored job, a

two-door hardtop. This close he made out the name, a strange one to

him—Facel-Vega, what the hell was that? One of these

twenty-thousand-buck foreigners, probably with a TV director or a

movie actor or something like that driving it, just to be different

and show he had the money. Walsh stopped at the driver's window. "May

I see your operator's license, please?" he asked politely.

The driver was a slim dark fellow with a black

hairline moustache, a sleek thick cap of black hair, a long straight

nose, and a long jaw. He said just as politely, "Certainly,

officer," and got out his wallet, correctly slid his license out

of its plastic envelope himself, and passed it over.

There was a woman beside him, a good-looking redhead

who seemed to be having a fit of giggles for some reason.

Walsh checked the license righteously, comparing it

with the driver. A Mex, he was, and quite a mouthful of name like

they mostly had: Luis Rodolfo Vicente Mendoza. The license had been

renewed within six months and matched him all right: five-ten, a

hundred and fifty-five, age thirty-nine, eyes brown, hair- Walsh

said, "You know, Mr. Mendoza, you were exceeding the limit by

about fifteen miles an hour." He said it courteously because

that was part of your training, you were supposed to start out anyway

being polite; but he felt a little indignant about these fellows who

thought just because they had money and a hot—looking expensive car

the laws weren't made for them.

The driver said, "You're perfectly right, I

was." He didn't even point out that practically everybody

exceeded the limit in these slow zones; he accepted the ticket Walsh

wrote out and put his license back in its slot, and Walsh, getting

back in the squad car, was the least bit disappointed that he hadn't

made the expected fuss.

It wasn't until his tour was over and he reported

back to his precinct station that he found out what he'd done. It was

the car that had stayed in his mind, and he was describing it to

Sergeant Simon when Lieutenant Slaney came in.

". . . something called a Facel-Vega, ever hear

of it?"

The sergeant said it sounded like one of those

Italians, and the lieutenant said no, it was a French job, and what

brought it up? When he heard about the ticket, a strangely eager

expression came over his face.

"The only Facel-Vega I know of around here—what

was the driver like, Walsh?"

"He was a Mex, sir—why? I mean, his license

was all in order, and the plate number wasn't on the hot list.

Shouldn't I—?"

"And his name," asked Slaney in something

like awe, "was maybe Luis Mendoza?"

"Why, yes, sir, how—"

"Oh, God," said Slaney rapturously, "oh,

brother, this really makes my day! Walsh, if I could christen you a

captain right now I would! You gave Luis Mendoza a ticket for

speeding? You don't know it, but you just made history, my boy—that's

the first moving-violation ticket he's ever had, to my knowledge."

"You know him, Lieutenant?"

"Do I know him," said Slaney. "Do I—?

I suppose he had a woman with him?"

"Why, yes, there was a redhead—a pretty one—"

"I needn't have asked," said Slaney. "There

always is—a woman, that is, he's not particular about whether it's

a blonde or what. He looks at them and they fall, God Almighty knows

why. Do I know him, Says you. For my sins I went through the training

course with him, eighteen years back, and we worked out of the same

precinct together as rookies. And before we both got transferred, the

bastard got a hundred and sixty-three dollars of my hard-earned money

at poker, and two girls away from me besides. That's how well I—"

"He's a cop?" said Walsh, aghast. He had a

horrid vision of riding squad cars the rest of his life, all

applications for promotion tabled from above. "My God, I

never—but, Lieutenant, that car—"

"He's headquarters—Homicide lieutenant. The

car—wel1, he came into the hell of a lot of money a couple of years

after he joined the force—his grandfather turned out to've been one

of those misers with millions tucked away, you know? Oh, boy, am I

goin' to rub his nose in this!" chortled Slaney. "His first

ticket, and from one of my rookies!"

"But, Lieutenant, if I'd known—"

"If you'd known he was the Chief you'd still

have given him the ticket, I hope," said Slaney. “Nobody's got

privileges, you know that."

Which theoretically speaking was true, but in

practice things weren't always so righteous, as Walsh knew. He went

on having gloomy visions for several days of a career stopped before

it started, until he came off duty one afternoon to be called into

Slaney's office and introduced to Mendoza, who'd dropped by on some

headquarters business. Slaney was facetious, and Walsh tried to

balance that with nervous apology. Lieutenant Mendoza grinned at him.

"Cut that out, Walsh, no need. Always a first

time for everything. The only thing I'm surprised at is that it was

one of Bill Slaney's boys—I wouldn't expect such zealous attention

to duty out of this precinct."

"Why, you bastard,” said Slaney. "Half

your reputation you got on the work of your two senior sergeants, and

I trained both of 'em for you as you damn well know."

"Yes, Art Hackett's often told me how glad he

was to be transferred out from under you," said Mendoza amiably.

All in all, Walsh was enormously relieved; despite

his rank and his money Mendoza seemed to be a regular guy.

That happened in January;

a month later, the memory of this little encounter emboldened Walsh

to go over Lieutenant Slaney's head and lay a problem before the

headquarters man.

* * *

"I've got no business to be here, Lieutenant,"

said Walsh uneasily. "Lieutenant Slaney says I'm a damn fool to

waste anybody's time about this." He sat beside Mendoza's desk

stiffly upright, and fingered his cap nervously. He'd called to ask

if he could see Mendoza after he came off duty, and was still in

uniform; he was on days, since last week, and it was six o'clock, the

day men just going off, the night staff coming into the big

headquarters building downtown with its long echoing corridors.

"Wel1, let's hear what it's about," said

Mendoza. "Does Slaney know you're here?"

"No, sir. I've got no business doing such a

thing, I know. I asked him about it, sir, and he said he wouldn't ask

you to waste your time. But the more I got to thinking about it . . .

It's about Joe Bartlett, sir, the inquest verdict yesterday—"

"Oh?" said Mendoza. He got up and opened

the door. "Is Art back yet‘?" he asked the sergeant in

the anteroom.

"Just came in, want him?" The sergeant

looked into the big communal office that opened on the other side of

his cubbyhole, called for Art, and a big broad sandy fellow came in:

the sergeant Walsh remembered from last Friday night and yesterday at

the inquest. He wasn't a man to look at twice, only a lot bigger than

most—until you noticed the unexpectedly shrewd blue eyes.

"I thought you'd left, now what d'you want? I

just brought that statement in—"

"Not that. Sit down. You'll remember this young

fellow, he's got something to say about the Bartlett inquest. You

handled that, you'd better hear it too."

"Bartlett," said Sergeant Hackett, and sat

down looking grim. Nobody liked random killings, but the random

killing of a cop, cops liked even less.

"I don't think that inquest verdict was right,"

blurted Walsh. "I don't think it was those kids shot Joe.

Lieutenant Slaney says I'm talking through the top of my head, but—I

tried to speak up at the inquest yesterday—maybe you'll remember,

Sergeant, I was on the stand just before you were—but they wouldn't

let me volunteer anything, just answer what they asked."

"What was it you wanted, to say? Didn't you tell

your own sergeant about it?"

"Well, naturally, sir—and the lieutenant—and

they both think I'm nuts, see? Sure, it looks open and shut on the

face of it, I admit that. Those kids'd just held up that market, they

were all a little high, and they weren't sure they'd lost that first

squad car that was after them—maybe they thought we were the same

one, or maybe they didn't care, just saw a couple of cops and loosed

off at us. We were parked the opposite direction, but they might've

figured, the way the coroner said, that that first car had got ahead

and gone round to lay for them."

Which had been the official verdict, of course: that

those juveniles, burning up the road on the run from the market job,

had mistaken the parked squad car for the one that had been chasing

them and fired at it as they passed, one of the bullets killing

Bartlett. They'd already shot a cashier at the market, who had a

fifty-fifty chance to live.

"They say, of course, that they never were on

San Dominguez at all, never fired a shot after leaving the market,"

said Hackett.

"Yes, sir, and I think maybe they didn't. I—”

"Giving testimony," said Mendoza, "isn't

exactly like talking to somebody. Before we hear what brought you

here, Walsh, suppose you give me the gist, in your own words, of just

what did happen. I know Sergeant Hackett's heard it already, and I've

read your statement, but I'd like to hear it straight."

“

Yes, sir. We were parked on the shoulder, just up

from Cameron on San Dominguez. That's almost the county line, and one

end of our cruise, see. We'd just stopped a car for speeding and I'd

written out the ticket. Joe was driving then and I was just getting

back in, and in a second we'd have been moving off, when this car

came past the opposite in way and somebody fired at us from it. Four

shots. It must've been either the first or second got Joe, the doctor

said, by the angle—and it was just damned bad luck any of them

connected, or damned good target shooting, that's all I can figure.

The car was going about thirty. The shots came all together, just

about as it came even with us and passed, and the way things were I

hardly got a look at all. Joe never moved or spoke, sir, we know now

the shot got him straight through the head . . ." Walsh stopped,

drew the back of his hand across his mouth. He'd liked Joe Bartlett,

who'd been a good man for a rookie to work with, easy and tactful on

giving little pointers. Ten years to go to retirement, Bartlett, with

a growing comfortable paunch and not much hair left and always

talking about his kids, the boy in college, the girl still in high

school. Also, that had been Walsh's first personal contact with

violence, and while he'd kept his head it hadn't been a pleasant five

minutes. "He slumped down over the wheel, I couldn't get at the

controls until I'd moved him, it was—awkward, you can see that. I

think I knew he was dead, nothing to be done for him—I just

thought, got to spot that car .... I shoved him over best I could to

get at the wheel, but by the time I got the hand brake off and got

her turned, my God, it wasn't any use, that car was long gone. I was

quick as I could be, sir—"